Chapter 19 – Mark Smith (D1SOP19)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 19

Understand the principles of professional decision-making and be able to make informed decisions within the context of competing demands including those relating to ethical conflicts and available resources.

|

KEY TERMS Principles Context Leading decision- making Social care staff team Risk-averse culture

|

Social care is … about keeping the service user at the centre of all decisions made, and achieving a balance between care, the environment, the context in which the decision is being made, and the resources available. |

TASK 1

Reflect on a decision you found difficult to make, reflect on factors that shaped the decision. Were you satisfied with the outcome? If you had to make the same decision today, what would you do differently and why?

Principles of Decision-making

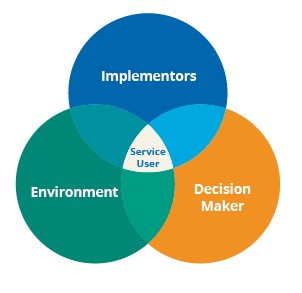

Working for 30 years as a social care worker I have experienced the challenges and complexities of professional decision-making. As social care workers, we are in a constant process of decision-making during our day-to-day practice. This chapter is written from my experience of making decisions in children’s residential care and special care services. Based on my experience, there are three key principles to consider when we make decisions: the decision-maker; the decision implementors; and the decision-making environment, with the service user or young person at the centre. The decision-maker and the decision-making environment are the key principles that influence the decision and the staff team are the implementors who turn the decision into the plan. However, those of us working in social care must also acknowledge the client, the young person we are working with, as the centre of the decision-making process. Social care work is about achieving the balance between the individual making the decision, the young person’s care that as a social care worker you are managing, the environment and context in which the decision is being made and, finally, the resources available.

The final key principle in decision-making is ensuring that the client group or person we are working with is involved to the greatest possible extent in the decisions made about their lives, at the level that is most appropriate for them. Social care workers are uniquely placed to be able to support the client in making decisions about their lives. It is my opinion that social care staff are the strongest advocates for the people we work with. This advocacy role in the decision-making process comes from working directly with the client group. This is especially true of those of us who work in residential care. It is therefore important that we support the client/young person in meetings and discussions about them.

This role of advocacy and supporting the decisions about the individual client primarily occurs within the multi-disciplinary team. It can also occur in staff meetings and managers’ meetings, but the key decisions are made within the multi-disciplinary framework. The process used by the multi-disciplinary team is seen as the most comprehensive decision-making process and the best way of making decisions about how a young person’s care plan should proceed. However, a number of social care workers have shared negative experiences of decision-making at multi-disciplinary meetings. Brown (2016), in her research on relationship-based practice, highlighted that workers frequently felt that their role and contribution were not sufficiently recognised and acknowledged. In the inter-agency working relationships between the residential childcare worker, the social worker and the Gardaí, residential workers frequently perceived their relationship with the young person was ignored and undervalued. The notion of ‘the closer to the child, the further from the decision’ emerged from the data. Interviews with residential workers highlighted that although they shared decisions with professionals, they felt their contributions had less influence than those of other professionals, whom they described as ‘relative strangers to the child’, thereby undermining their professional contribution (Brown 2016). Social care workers therefore need to articulate these concerns prior to multi-disciplinary meetings and in supervision sessions. If possible, the young person should be involved in this multigroup. In our role as social care workers, we support the client’s decision-making in a number of ways. Primarily we support the young person through key working and the development of the client’s placement plan and development goals. These meetings can therefore be the most important meetings in a young person’s care life.

Context of Decision-making

In social care, particularly in residential care, there are different types of decisions. The first type (in the moment) is the decision made when emotions are running high and there is a huge amount of tension. These decisions are often made in the context of an extreme situation. People who have worked in residential care will understand and have experienced these situations and how these decisions are made.

The other type of decision (after the moment) is made by the staff who are not involved and have not experienced the extreme emotion and should therefore be able to make the decision in a reflective environment. The important principle in this context of decision-making is having confidence in your own professional knowledge and practice experience and that of your colleagues. This means that most of the after-the-moment decisions made about the programme of care for young people are made within the following frameworks: child in care reviews; multidisciplinary meetings; staff team meetings; and management meetings. However, making the decisions is often the easy part of the task. Ensuring that the decision is implemented by the team is the real skill, particularly within the context of competing demands, including those relating to ethical conflicts and available resources.

TASK 2

Read page 28 of the Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics for Social Care Workers (SCWRB 2019) for the suggested procedure for decision-making.

Leading Decision-making

As Smith (2009) identified, in residential care decision-making is a complex task that has to be managed and balanced. Harrison (2006) agreed with this point, but he also identified that decision-making would be improved if management focused on the critical issues. Strategic planning is beneficial in identifying what critical issues will have to be responded to. Strategic planning can also map out the direction where the organisation wants or needs to go (Barksdale & Lund 2006).

Organisational priorities and potential critical issues that need to be addressed can be dealt with, and the benefit of this process is improved service performance. Barksdale and Lund (2006) outlined ten steps needed for strategic planning, which are adapted here to apply to social care practice.

|

Steps |

Details |

|

1 |

Laying the foundations of the care plan or the decision in consultation with the service user, decision-maker and implementors. |

|

2 |

Understanding the context and environment influencing the decision or plan. |

|

3 |

Collecting relevant information. |

|

4 |

Analysing the information and how it will impact the person, plan or decision. |

|

5 |

Stating the mission, vision and values of the service. |

|

6 |

Prioritising needs and identifying risks. |

|

7 |

Designing the plan and outlining the desired goals (three months, six months, one year, etc.). |

|

8 |

Balancing needs, goals and resources. |

|

9 |

Documenting and communicating the plan. |

|

10 |

Maintaining the plan. |

Our management group are working on introducing a ‘servant leadership’ type of management model (Spears 2002). This model is a long-term investment in the staff team which focuses on how to support the staff group and works on developing a strong culture within the organisation. Servant leadership looks at developing members of the team in a supportive capacity that will get the best out of the staff team who are working in the service.

In recent years, a number of institutions have jettisoned their hierarchical decision-making and replaced it with a servant leader approach. Servant leadership advocates a group-oriented approach to analysis and decision-making as a means of strengthening institutions and improving society. It also emphasises that the power of persuasion and of seeking consensus is superior to the old top down form of leadership. (Spears 2002: 9)

Investing in the team is important as the strength of the team is critical in carrying out decisions made by managers. As Harrison (2006) described, management is all about getting things done through other people. An important principle in decision-making is knowing whether the staff are able to carry out the decision. There may be a number of reasons why they are not able to carry out the decision, and some of these reasons may be obvious. For example, asking a new member of the staff team to deal with a young person who has a history of challenging and threatening behaviour to implement a task could result in a reaction from the young person. This is not a good use of resources and is not planning for success. In order to be ethical in our decision-making we have to be mindful that we are frequently going to be confronted with dilemmas of rights versus responsibility, of confidentially, choice and autonomy. There can be conflicts in the staff team when faced with ethical decisions and this can be challenging for the social care team and management. Some other subtler reasons might be resource issues and not enough staff being on duty to carry out the task successfully.

What has to be guarded against are two issues. The most important of these is that the staff deliberately do not carry out the decision because they ‘feel that they know best’, and/or that ‘the decision is wrong’. It is therefore important to have a culture within the organisation that can guard against non-compliance and that the staff team and manager have a shared vision. We need to be cognisant of adhering to CORU’s Code of Conduct, which states that a social care worker must ‘be able to justify any decision you make within your scope of your practice, you are always accountable for what you do, what you fail to do and for your behaviour’ (SCWRB 2019: 14). Also, non-compliance can occur if the staff team do not have the required skill set to carry out the task. Smith, in his book Rethinking Residential Care (2009), states that when he first worked in residential care, high-end incidents were rare, but when he left many years later, they had become a daily occurrence. He put this down to the fact that residential care has become more specialised, and as such, the young people with the most challenging behaviour are being placed together without the balance of other young people who have internalised the culture and are able to teach the existing culture to new admissions to the service.

Budgets also affect how and what decisions social care staff and managers make. What effect, if any, will the decision have on the service’s budgets and the resources of the organisation? Social care, like all other services, must live within its budgetary limits. There will always be tension between frontline workers who are client-facing and who will argue about the need for more comprehensive services, and those social care staff who are the budget holders. This tension has been in existence since the development of services and it has an impact both on the delivery of services and, inevitably, on our decision-making process.

Social Care Staff Team

When I first started in social care back in the 1980s, staff turnover was low, and residential care was seen as a positive career choice. People spent many years in the same setting, which allowed new members the opportunity to learn from an established team, and to grow and develop their own skills in building relationships and managing young people. In my experience an established staff team also had the time to mentor and support new staff. Smith (2009) notes that ‘in the past, experienced staff picked up how to work with groups through an apprenticeship model where they learned the tricks of the trade from older hands’ (2009: 88). In my own experience I was the new staff for almost a year. This is compared to residential services where there is considerable turnover and the expectation is for staff to stay only between three and five years in the residential care setting. This has resulted in a loss of ‘corporate knowledge’ and constantly having to train new staff, which leads to a poor retention cycle.

In the absence of cohesive experienced social care teams, it is important that the care staff team have a good culture and feel supported by the management structure. Staff need to feel that they can grow in their role as social care workers and be able to develop their decision-making capabilities. Organisations should strive to become learning organisations as this gives the staff the best chance of developing. However, this learning culture has to be created and to be created the senior management team have to invest in the social care team, and this is a 24/7 process: ‘becoming a learning culture has to rest on the values and style that is driven and championed by the senior team and becomes part of the operating fabric of the way the service runs’ (Stanley & Lincoln 2015: 200).

Creating stability and a stable staff team in which the social care worker is able to make decisions is one of the first goals of managing a team. In research conducted by Roncalli and Byrne (2016) into psychologists working in the mental health services in Ireland they found that supervisors had a seminal role in developing the staff who worked with them. The senior staff needed to show appreciation to the new staff, offer constructive feedback and be able to reward innovative practices conducted by these newer staff. Once you, as leader/manager, can rely on your staff to make the right decision at the right time you can tackle the other important principles of decision-making.

TASK 3

Think of an example of constructive feedback you received from a manager or supervisor. What was the feedback and what impact did it have on you?

Risk-Averse Culture

Professional decision-making in a risk-averse culture has sadly become part of my experience of working in special care. Services that are involved with young people at risk can often move towards making defensive decisions and practices. This is due to the risks that the young person may have demonstrated or was exposed to prior to their admission to special care. It can also be described as a societal shift in the avoidance of harm and not wanting to re-expose a young person to risk they were involved in prior to admission to special care. Within this risk-averse climate, preventing the young person coming to harm drives decisions. As Brown (2018: 658) describes, society views harm as an outcome of irresponsible behaviour and the social care worker and the multidisciplinary team often feel that, if some harm befalls the young person, their decisions will be viewed through this black and white lens. Research by Kirkman and Melrose (2014) has highlighted the damage done to young people by these defensive cultures. As social care staff, we have to ensure that we are working with the young person to ensure that the best decision is made with them, and this is not just about avoiding risks.

Failure to comply with standards will have a negative impact on the service and could ultimately affect the registration of the service. We make decisions as professionals, and we need to be able to stand over the decisions that we have made and believe we have made them for the right reasons. Improved decision-making within an organisation leads to increased benefits for both young people and staff and helps to foster a stable culture.In conclusion, making decisions on a professional level is a very complex task. However, we engage in this task throughout our working day. These areas are key to supporting good decision-making. However, these principles on decision-making are only as good as the team that is implementing the decisions. Residential care’s history in Ireland has not been seen as one in which a healthy reflective culture existed. Residential care still carries a stigma both for the young people who are resident and for the social care workers who practise in the services. This is possibly due to constant ethical dilemmas that staff have to consider when dealing with vulnerable people on a 24/7 basis. Therefore, it is extremely important that social care staff who work in these areas are aware of their decisions and the impact these decisions will have on their client group. As discussed above, good decision-making is supported by good leadership. This leadership has to have a clear vision that both supports the client’s rights and also focuses on the development of the staff member. In any ethical issue, social care workers must work through the ethical considerations to inform their decision-making. In summary, it is through reflection, ethical considerations, supervision and inclusion of the voice of service user that we work towards excellence in social care practice.

Tips for Practice Educators

When making decisions I have found it very useful to discuss the potential decisions with a trusted colleague. In these discussions it was helpful to consider all possible actions, even the possibilities that might sound ridiculous, and then talk through the possible outcomes of each decision. It has been my experience that what starts off as a ridiculous suggestion often turns out to be close to the desired outcome with a successful conclusion for all parties.

- Provide three examples of recent decisions made by you and your colleagues and explain the process, what was considered, what was rejected and why and how this decision was finalised.

- If possible, allow your student to attend team meetings and give them the task of focusing on the decision-making process in the team, who made the suggestion, who spoke, etc. This can be the starting point for your next supervision session.

References

Barksdale, S. and Lund, T. (2006) 10 Steps to Successful Strategic Planning. Virginia: Association for Talent Development ASTD Press.

Brown, T. (2016) ‘Hear Our Voice: Social Care Workers’ Views of Effective Relationship-based Practice’, PhD thesis, Queen’s University, Belfast. Retrieved from <http://isni.org/isni/0000000464238827>.

Brown, T., Winter, K. and Carr, N. (2018) ‘Residential child care workers: Relationship based practice in a culture of fear’, Child and Family Social Work 23: 657-65.

Harrison, P. (2006) Managing Social Care: A Guide for New Managers. Dorset: Russell House.

Kirkman, E. and Melrose, K. (2014) ‘Clinical Judgement and Decision-Making in Children’s Social Work: An Analysis of the “Front Door” system’, research report, Department for Education, UK.

Roncalli, S. and Byrne, M. (2016) ‘Relationships at work, burnout and job satisfaction: A study on Irish psychologists’, Mental Health Review Journal, 21(1), 23-36 <https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-01-2015- 0002>.

Smith, M. (2009) Rethinking Residential Care: Positive Perspectives. Bristol: Policy Press/University of Bristol.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2019) Social Care Workers Registration Board code of professional conduct and ethics. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at https://coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for- social-care-workers.pdf.

Spears, L. (2002) ‘Tracing the Past, Present, and Future of Servant-Leadership’ in L. Spear and M. Lawrence (eds), Focus on Leadership: Developments in Theory and Research (pp. 1-16). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stanley, T. and Lincoln, H. (2015) ‘Improving organisational culture: The practice gains’, Practice: Social Work in Action 28(3), 199-212, 22 September.

Taylor, B. and Whittaker, A. (2018) ‘Professional judgement and decision-making in social work’, Journal of Social Work Practice 32(2): 105-9, DOI: 10.1080/02650533.2018.1462780.