Chapter 21 – Jennifer Mc Garr (D1SOP21)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 21

Be able to maintain professional boundaries with service users within a variety of social care settings and be able to identify and manage any associated challenges

|

KEY TERMS Professional boundaries Social care settings Associated challenges

|

Social care is … a profession concerned with meeting the needs of individuals, groups and communities through evidence-informed and strengths-based approaches to practice. |

Social care work is grounded in building capacity, in empowering service users and in recognising the individual as the expert of their own experience (Byrne-Lancaster 2014; Branfield & Beresford 2006; Lalor & Share 2013). Much of the work happens in the life space of the individual, where everyday opportunities and events are used to maximise growth and development (Ward 2002). This work is relational; the relationship between the worker and service user is the key ingredient in mobilising change, and the social care worker must draw on the ‘self’ in creating a relationship which is authentic and meaningful (Ingram & Smith 2018; Lyons 2013; McHugh & Meenan 2013). In the delivery of this work, social care workers are mindful of the context in which such work occurs and are attuned to the wider social and political structures within society, which privilege some but exclude others (Byrne-Lancaster 2014; Thompson 2012). This means that social care workers walk a tightrope between adopting an individualised approach to practice while also recognising the wider social and cultural context in which the individual in embedded (McGarr & Fingleton 2020).

Professional Boundaries

Relationships are at the core of social care work (SCWRB 2019; Ruch, Turney & Ward 2018). However, relationships can be complex and messy. Building meaningful and authentic connections with service users requires an awareness of boundaries and a constant renegotiation of our personal and professional selves (Ingram & Smith 2018). Boundaries are not an exact science. They are “nebulous, elusive and difficult to define” (McCann James et al. 2009: 108) and change according to the context and the relationship (O’Leary et al. 2012). At a most basic level, boundaries are “the parameters of the self” (Fewster 2011: 9) and we navigate personal and professional relationships through these parameters. We all occupy different roles in our lives, for example father, sister, partner, mother, worker, child. Each role has its own unique boundaries and expectations which determine how we engage with that relationship. The boundaries of what we might share, our use of touch, how we interpret the actions of the other, are unique to that individual relationship (Davidson 2009; Fewster 2011).

When we refer to professional boundaries, in essence we refer to the parameters of our professional selves. Cooper (2012: 11) defines professional boundaries as “a set of guidelines, expectations and rules which set the ethical and technical standards in the social care environment … (setting) limits for safe, acceptable and effective practice by workers”. However, personal and professional boundaries are not unrelated. Gender, culture, family background or religion shape our ‘limit-lines’ and how we engage in our personal and professional worlds (Cooper 2012). Furthermore, how we navigate relationships, including professional ones, can be a reflection of our internal working model (Bowlby 1969). How we engage and how we respond, particularly during times of stress, can be shaped by our own relational histories and the messages that we have received about what relationships are and how they function (Howe 2011). Therefore, the personal and professional selves are interrelated and boundaries can be dynamic and shifting. Workers are tasked with engaging in ongoing reflection to understand how values, attitudes, beliefs and personal histories shape their work, as the self is “the principal tool of the social care worker” (Kinnefick 2006, cited in Lyons 2013: 102).

In a professional context, boundaries provide ethical parameters to work that is often dynamic, contested and unpredictable. Inherent within any professional relationship is a power imbalance between the worker and the service user (Cooper 2012; Davidson 2009). Professional titles, access to information or funding, the ability to provide or deny access to a service, all confer authority and can position the worker as the ‘expert’ in the situation (Cooper 2012) despite commitments to co-produced, participatory practice. Boundaries reduce the risk of abuse, exploitation and discrimination, and provide a sense of certainty for both workers and service users in relation to role and expectations (Cooper 2012). In addition, with relationship based practice at the core of social care work (Brown, Winter & Carr 2018; SCWRB 2019), boundaries provide “a safe framework for this relationship to exist in” (Cooper 2012: 32).

Professional boundaries protect both staff members and service users in the following ways:

- Boundaries help service users to feel safe (Cooper 2012). Consistent, trustworthy relationships create feelings of safety (SAMHSA 2014) and contribute to what Winnicott (1960: 591) termed the “holding environment”. Service users often test these boundaries. Their behaviour may be communicating a need to feel safe, and they may be testing you to see if you can meet that safety need. Furthermore, some service users may struggle with interpersonal relationships. Through role modelling appropriate boundaries we provide relational safety while also supporting service users to work on their own boundaries and to navigate personal and professional relationships (Cooper 2012).

- Boundaries ensure the needs of the service user remain at the forefront of practice (McCann James et al. 2009). We all have our own needs, wants and desires, which can play out at a subconscious level. Understanding our motives, reactions and behaviours are key to practising in a reflexive way and ensuring that the care we give is person-centred and responsive to the service user’s needs (Cooper 2012).

- Boundaries can reduce the risk of burnout (Cooper 2012). Through managing our responses and maintaining controlled emotional involvement we protect against compassion fatigue and minimise the processes of transference3 and counter-transference4 (McCann James et al. 2009). See Chapter 70 D5 SOP9 for a more detailed discussion of these processes.

- Transference occurs when the service user projects feelings about a significant person on to a worker, for example a service user who reacts aggressively to a worker because (s)he reminds them of someone from their past (Cooper 2012).

- Counter-transference occurs when workers project feelings about a person or experience in the past onto something that is happening in the present, for example a worker who lacked parental attunement in childhood and feels rejected by a service user who will not engage (Cooper 2012).

- We work to support autonomy, minimise dependency and build capacity (Cooper 2012). Relationships in which workers are over-involved or are uninterested and detached can diminish resilience and undermine strengths-based practice (Davidson 2009).

Therefore, poor or mismanaged boundaries can contribute to both service user and worker stress and undermine the therapeutic potential of the relationship.

The Davidson Model

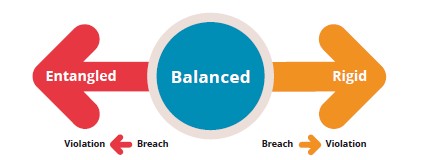

Social care practice is complex and nuanced, and knowing where to draw the boundary lines can prove challenging at times for even the most experienced worker. Davidson (2009) offers a framework for thinking critically about behaviour and understanding boundaries within professional relationships. Based along a continuum, she identifies three categories or boundary ranges: (a) entangled, (b) balanced and (c) rigid (see Figure 1) (Davidson 2009). Where boundaries have become compromised, workers may engage in boundary breaches or boundary violations (located at either end of the continuum). Boundary breaches refer to actions that have “transgressed a commonly accepted standard of behaviour for reasons that may be understandable”, whereas violations are actions whereby “a professional uses the relationship with the client to meet their personal need at the expense of the client” (Davidson 2009: n.p). According to Cooper (2012), boundary violations lead to the exploitation and abuse of service users.

Workers who display balanced boundaries adopt an authentic manner centred on meeting the service user’s needs (Davidson 2009). They are respectful, reflective in their practice, are aware of their feelings and motivations, and use their professional judgement accordingly (Davidson 2009; Cooper 2012). With entangled boundaries, the worker often subconsciously meets their own needs through the professional relationship (Davidson 2005). Boundaries become entangled when workers are over-involved in service users’ lives or when workers give too much of themselves to the detriment of their other relationships. For example, the worker who becomes upset or personally affronted when the service user does not attain a particular goal, or the worker who ‘gives it their all’ to the detriment of their own self-care and emotional and physical well-being (Davidson 2009). Commitment, passion and empathy are admirable traits for those working in helping professions, however over-involvement can sometimes stem from a need to “fix things for people, to make things right or undo the impact of injustices…in the world” (Cooper 2012: 176) or a tendency towards co-dependence within relationships (Cooper 2012). Workers who have rigid boundaries deliver care which is inflexible and unresponsive to the needs of the client, often ploughing ahead with their own agenda (Davidson 2009), for example the worker who cannot use discretion when implementing the organisational rules, who gives nothing of themselves or struggles to create meaningful connections. Rigid boundaries “create substantial distance within the relationship” (Davidson 2005: 518) and amplify the power imbalance between worker and service user.

Boundary ranges are not fixed. Some social care workers may operate within the same boundary range for all their professional relationships; others may find themselves falling within a particular boundary range around a certain personality type, issue or situation (Davidson 2005). This is where reflective practice and supervision come into play, to create a space to identify triggers, unconscious motivations and patterns of behaviour.

TASK 1

Reflective Task

Using Davidson’s model outlined above, where do you place yourself on the continuum in relation to your work relationships?

Consider your relationships with service users, members of your staff team and management.

Why have you placed yourself there?

What impact might your behaviour have on the service user?

If required, what changes can you make to your practice in order to achieve balanced boundaries?

Social Care Settings

Social care workers work in a multitude of settings, from addiction services to disability services, residential childcare, mental health services, homeless services and family support, to name but a few (Lalor & Share 2013). Prescriptive rules do not easily translate, as each setting is unique. Boundaries are contextual and dynamic; the profile and needs of the service user, along with the organisational policy, physical setting and wider societal and cultural context, will shape what is acceptable within each particular setting (Davidson 2005; O’Leary et al. 2012). Therefore, it is important to tune in to where your boundaries lie, to understand what you view to be acceptable, and to be open to revising these as you reflect on and grow in your everyday practice.

Associated Challenges

There are some behaviours that are clearly unacceptable, and are in complete contravention of CORU’s Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics for Social Care Workers (SCWRB 2019). While major boundary violations are easily identifiable (for example, having an intimate relationship with a service user), they rarely occur in isolation and have generally been preceded by minor boundary crossings (Cooper 2012). We all have a responsibility to safeguard service users and hold ourselves and our colleagues to safe and accountable practice. Students will have explored ethical parameters of practice in Chapter 1 D1 SOP 1, where the discussion centred on ethical practice being the balance between professional autonomy and accountability. Boundaries are also discussed in Chapter 7 D1 SOP7, where graduates are expected to “be familiar with the provisions of the current Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics for the profession” (SCWRB 2017: 4). Chapters 1 and 7 contribute to our understanding of the nuanced nature of boundaries which, in day-to-day practice, can pose challenges for social care students and seasoned workers alike. Boundaries can be “difficult to identify but easy to cross” (Davidson 2005, p. 511) and “grey zones” are frequently present in the work (Davidson 2009: n.p). According to O’Leary et al. (2012) boundaries are about connection, not separation; therefore boundaries are fluid, not fixed. Students preparing for placement often find this fluidity frustrating, and lament the lack of a clear rule book.

Boundary Grey Zones

In social care work it is common to encounter “grey zones”, “circumstances where pre-scribed answers do not easily apply” (Davidson 2009: n.p). For example, physical contact is often a contested issue in social care settings: When is touch appropriate? What level of touch should I use? Should I wait for the service user to initiate this? Cooper cautions against the use of physical contact, suggesting that this should be kept “to a minimum and to a level appropriate to your role and your relationship” (2012: 45). He suggests that touching the hand or the lower arm may be safe way of using touch in the work. Byrne questions whether our current care context has led to a sanitised version of care that is devoid of love. He argues that, particularly in relation to working with children in state care, “the withdrawal of physical affection is arguably an abuse in itself” (2016: 154). This is an example of two valid yet conflicting messages, which can prove confusing for the social care student.

Sharing personal information is another area that often causes discomfort: What do I share? How much do I share? Could this information come back to haunt me at a later date? Relationships are fundamental to the work of the social care worker. Yet it is only through sharing something of ourselves that genuine and authentic connections are made. A student of mine offered this advice:

“For me it was important to carefully select which parts of myself that I wanted to share with both service users and the management team. I learned to use common conversation such as sport or TV programmes as a way to form a relationship and to gather an understanding of the person’s lifestyle” (3rd-year student). [1]

Social care workers may be drawn to the work as a result of personal experience, for example a worker in a homeless service who had previously experienced homelessness, or a person who had struggled with addiction now working in an addiction service (Cooper 2012). Workers in these contexts sometimes share something of their own experience to connect with the service user, to encourage change and to create hope. In circumstances like this it is crucial to reflect on our motivation for sharing the information by asking: (a) What am I planning to share?; (b) Why am I sharing this information?; and, most important, (c) How will it help my service user? (Cooper 2012).

Cooper (2012) cautions against favourable treatment of some service users over others and that the giving and receiving of gifts can signify the marking of a special relationship. Yet key-working, a cornerstone of person-centered and relationship-based practice, could be considered a special relationship therefore definitive rules can be difficult to apply here. Through an attachment lens, one of the functions of the key working intervention is to provide consistency, continuity and relationship security (Payne 2009), and key workers sometimes give small gifts at birthdays or Christmas as part of this role. Aside from the key working relationship, in some organisations small tokens of appreciation are accepted but valuable gifts are not. In others, gifts are not accepted or are shared amongst the staff team. One might need to ask: What is the nature of the gift? Why was the gift given? What monetary value is attached to the gift? What is the organisational policy on giving and receiving gifts? A student recently shared this experience with me.

“On one occasion a service user brought me a gift. I was unsure about how to approach the situation and felt uncomfortable declining the gift. I explained to them that I was not allowed to accept gifts within the organisation. The relationship was not affected and I was able to maintain the trust and respect of the service user as I was honest” (3rd-year social care student).[2]

Other grey zones include bumping into a service user outside the service and knowing how to respond, or beginning and ending the relationship appropriately. These scenarios are not always straightforward and require an individualised response based on the needs of the service user. A student shared how she supported a positive ending:

“During my last week of placement in a disability service, a service user asked if they could have my phone number as he was not going to be there on my last day. I explained that it is not appropriate to give out my personal number. After being asked multiple times, I agreed to give my email to the staff and the staff could help them to type up an email to me. In other circumstances, I would have explained that maintaining contact after my placement was not appropriate. However, this service user was especially attached to me and found endings difficult. It aided in preventing feelings of abandonment by providing a sense of closure, while still ensuring any contact made was formal and regulated through staff” (3rd-year social care student).[3]

Much of the work happens in the grey and working interpersonally with service users can present challenges. When working within these grey-zones, one must:

- Pay attention to the power differential that exists within the professional relationship;

- Engage in ongoing self-reflection to understand our own motivations, feelings and behaviours;

- Remember that the relationship with each service user is different; and

- Work within the parameters of ethical practice and sound professional judgement, including paying attention to organisation policy and context.

Maintaining Balanced Boundaries

Boundaries shape the type of relationship that is forged and the expectations and interactions attached to that relationship (Davidson 2009; O’Leary et al. 2012). Each pie might have different ingredients or look slightly different – for example, workers may have the same title or job description, but how they go about the work is unique to their working style. However, a crust that is too rigid holds the relationship in a way that is inflexible. Conversely, a crust that is too soft lacks solidity and reassurance. Both compromise the “live adaptation to the [service user’s] needs” (Winnicott 1960:563), which is the essence of the holding environment.

Boundaries shape the type of relationship that is forged and the expectations and interactions attached to that relationship (Davidson 2009; O’Leary et al. 2012). Each pie might have different ingredients or look slightly different – for example, workers may have the same title or job description, but how they go about the work is unique to their working style. However, a crust that is too rigid holds the relationship in a way that is inflexible. Conversely, a crust that is too soft lacks solidity and reassurance. Both compromise the “live adaptation to the [service user’s] needs” (Winnicott 1960:563), which is the essence of the holding environment.

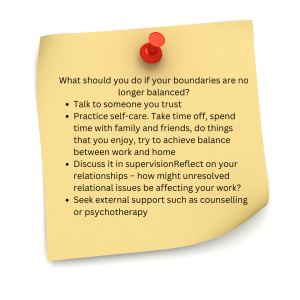

There is no doubt that we all experience times where our boundaries are not well managed. Perhaps we overshared or became too invested in our service user’s goals or choices. Or the opposite; we experienced disconnection and apathy, or shared nothing of ourselves. According to Davidson (2005), this is most likely to happen when the worker is feeling vulnerable or is not maintaining good physical and emotional self-care. We cannot care for others if we do not care first for ourselves.

Case Study 1

Mary has been working in social care for approximately 10 years and is currently working in a family support service. Mary has recently been allocated a case; a mother, Joyce, who is parenting alone, and her two children, aged six and eight.

Joyce has mental health issues and is struggling to cope. Her situation is compounded by social disadvantage, poor housing and the absence of support. Joyce had come to the attention of Tusla, the Child and Family Agency, due to concerns around alcohol, and the level of supervision and basic care received by the children. Following an assessment completed by the Social Work Department, Mary had been assigned to work with Joyce to support her around parenting. As part of the Child Protection Plan, Joyce had agreed to start a rehabilitation programme to tackle her alcohol misuse, had been attending her appointments and keeping to her plan.

Mary has personally found this case very draining. Growing up with a parent who had problems with alcohol, Mary knows first-hand the impact this can have on young children. Mary is worried that Joyce has started to slip. When Mary rang the clinic for an update on Joyce’s progress (with Joyce’s consent), the clinic informed Mary that Joyce had missed a couple of her appointments. This left Mary feeling very frustrated. The most recent conversation with Joyce about this became quite heated and Mary felt she lost control. This resulted in Joyce yelling at her to ‘Get out of my house and leave me alone.’

What is happening in this scenario?

Why did Mary react to Joyce missing her appointments?

What does Mary need to do next?

To conclude …

Boundaries are not an exact science (McCann James et al. 2009) and due to the diverse nature of social care settings, prescriptive rules cannot apply. Each setting has its own unique expectations and requirements, while working within the bounds of ethical, safe and quality practice. Social care work is relational, therefore the role of self cannot be underestimated (Ingram & Smith 2018). However, we must consider what ‘self’ we are bringing to practice. The first step towards building meaningful relationships with others is to start building a meaningful connection with oneself. Tuning into our own emotional world is key, along with practising self-care and using opportunities to reflect, question and grow. This is no doubt a lifelong endeavour; however, in the words of Aristotle, “Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom”.

TASK 2

Activities Cooper (2012) ‘How Tight Are Your Boundaries’. A self-assessment questionnaire to think about how you respond’ in Professional Boundaries in Social Work and Social Care: A Practical Guide to Understanding, Maintaining and Managing Your Professional Boundaries.

Tips for Practice Educators

Pre-placement

Students often feel anxious before going on placement about maintaining appropriate boundaries. They worry about making a mistake, not ‘getting it right’, or worst of all, not making it through their placement. Creating a safe space within the classroom to explore these concerns and tease out the nuances of boundaries is very important. Activities such as case studies based on ethical and boundary concerns can be a useful starting point, as can role plays based around common placement experiences, such as:

- a service user asks to add you as a friend on Facebook or for your telephone number

- a service user asks you out on a date

- a service user confides something of concern to you ‘as a friend’ and asks you not to tell anyone

- a member of your local community/neighbourhood accesses the service.

- you meet a service user on the bus on the way into town

Furthermore, individual reflective activities based around the student’s own experience and personal journey, for example listing what they feel comfortable sharing versus what they don’t feel comfortable sharing, can be valuable. These activities allow students to explore some of these issues within the confines of the classroom and to practise the skills that they will draw on in the placement setting.

During Placement

Students on placement should be able to provide their practice teacher with an example of boundaries within the workplace. Students could be asked to reflect on a time when they encountered a boundary challenge and how they resolved or addressed this. Practice educators do not expect students to ‘get it right’ all the time. However, it is important that the student has demonstrated some awareness of self, has engaged in critical reflection and can demonstrate the learning. My practice teacher used to say, “Once you stop learning, it is time to retire” and these words continue to ring true to me today.Students should also display a knowledge of whistleblowing and the Protected Disclosure Act 2014. Students may not have observed major boundary violations while on placement, however practice educators could present the student with a hypothetical scenario and ask them to identify the appropriate response.

References

Brown, T., Winter, K., and Carr, N. (2018). ‘Residential child-care workers: Relationship based practice in a culture of fear’. Child and Family Social Work, 23, pp. 657-665.

Bowlby, J. (1969) Attachment and Loss Vol. I: Attachment. London: Hogarth Press.

Branfield, F. and Beresford, P. (2006) Making User Involvement Work: Supporting Service User Networking and Knowledge. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Byrne, J. (2016) ‘Love in social care: Necessary pre-requisite or blurring of boundaries’ (Joint Special Issue, Love in Professional Practice), Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care 15(3) and International Journal of Social Pedagogy 5(1), pp. 152-8.

Byrne-Lancaster, L. (2014) ‘Outcomes of social care practice’, Cúram 48, pp. 10-12.

Cooper, F. (2012) Professional Boundaries in Social Work and Social Care: A Practical Guide to Understanding, Maintaining and Managing Your Professional Boundaries. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

CORU (2019). Update on the registration of social care workers-2019 updates. Available at: https://coru. ie/about-us/registration- boards/social-care-workers-registration-board/updates-on-the-social-care- workers-registration-board/update-on-the-registration-of-social-care-workers/ (accessed 24 January 2020).

Davidson, J.C. (2005) ‘Professional relationship boundaries: A social work teaching module’, Social Work Education 24(5), pp. 511-33.

Davidson, J.C. (2009) ‘Where do we draw the lines? Professional relationship boundaries and child and youth practitioners’, CYC-Online. Available at: <https://www.cyc-net.org/cyc-online/cyconline- oct2009-davidson.html> [accessed 24 January 2020].

Fewster, G. (2011) ‘Commandment 8: Gradually replace rigid rules with personal boundaries’, CYC- Online 154. Available at: <https://www.cyc-net.org/cyc-online/dec2011.pdf#page=4> [accessed 18 December 2019].

Government of Ireland (2014) Protected Disclosure Act 2014. Available at: <http://www. irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2014/act/14/enacted/en/html> [accessed 20 December 2019].

Howe, D. (2011) Attachment across the Lifecourse: A Brief Introduction. London: Palgrave.

Ingram, R. and Smith, M. (2018) Relationship Based Practice: Emergent Themes in Social Work Literature. Scotland: IRISS.

Lalor, K. and Share, P. (eds) (2013) Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (3rd edn). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Lyons, D. (2013). ‘Learn About Your “Self” Before You Work with Others’ in K. Lalor & P. Share (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (3rd edn). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, pp. 98-108.

McCann James, C., de Róiste, Á. and McHugh, J. (2009) Social Care Practice in Ireland: An Integrated Perspective. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

McGarr, J. and Fingleton, M. (2020). ‘Reframing social care within the context of professional regulation: Towards an integrative framework for practice teaching within social care education’. Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies, 20(2), pp. 26-42.

McHugh, J. and Meenan, D. (2013). ‘Residential Childcare’ in K. Lalor & P. Share (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (3rd edn). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, pp. 243-58.

O’Leary, P., Tsui, M. and Ruch, G. (2013) ‘The boundaries of the social work relationship revisited: Towards a connected, inclusive and dynamic conceptualisation’, British Journal of Social Work 43(1), pp. 135-53.

Payne, M. (2009). Social care practice in context. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ruch, G., Turney, D. and Ward, A. (2018) Relationship-based Social Work (2nd edn). London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) (2014). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services: Tip 57. USA: SAMHSA. Available at: <https://store.samhsa.gov/product/ TIP-57-Trauma-Informed-Care-in-Behavioural-Health-Services/SMA14-4816> [accessed 17 November 2020].

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2019) Social Care Workers Registration Board code of professional conduct and ethics. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at https://coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for- social-care-workers.pdf.

Thompson, N. (2012) Anti-discriminatory Practice: Equality, Diversity and Social Justice (Practical Social Work Series). England: Palgrave Macmillan.Ward, A. (2002) ‘Opportunity led work: maximising the possibilities for therapeutic communication in everyday interactions’, Therapeutic Communities 23(2), pp. 111-24.

Winnicott, D.W. (1960) ‘The theory of the parent-infant relationship’, International Journal of Psychoanalysis 41, pp. 585-95.