Chapter 22 – Danielle Douglas (D1SOP22)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 22

Be able to evaluate the effect of their own characteristics, values and practice on interactions with service users and be able to critically reflect on this to improve practice

|

KEY TERMS Self and social care Values Critical reflection Relationship

|

Social care is … about working in partnership to support and empower individuals and groups at a vulnerable time in their lives through relationship-building and the delivery of personalised programmes and interventions |

Self and Social Care

This proficiency requires social care workers to engage in continuous critical reflection to evaluate possible impacts of their own characteristics, values and practice on their interactions with service users. Reflecting on personal values and characteristics is an area of the human personality that has become known as the ‘self’ or sometimes the ‘self-image’ (Kidd & Teagle 2012: 65). This chapter has the dual objectives of conceptualising ‘self’ and suggesting ways of critically reflecting on the ‘self’.

Social care is a relationship-based profession in which the social care worker and service user work in partnership to identify needs, achieve goals and enhance quality of life. Social care workers strive to support and empower their service users and facilitate their voices at every opportunity. People who avail of social care services often have certain vulnerabilities or aspects of their life they are struggling with and require either short- or long-term interventions. Social care workers must always be acutely aware of the role they play in the lives of their service users and the possible impacts their values, characteristics and interventions have. To be able to evaluate the possible effects your ‘self’ have on the people you work with, you must first understand who the ‘self’ is and how it develops. Integral to this process is being aware of the values and characteristics that make up this self and the factors that contribute to the construction of self.

As a species capable of reflection and development, we having been asking ‘Who am I?’ for aeons, and despite the hundreds of thousands of academic articles and texts, and pop psychology self-help books, that attempt to address this question, a conclusive answer is yet to be determined. Rose (2012) offers four key characteristics that are useful for exploring the factors associated with self.

1. Self as Open to Change

It is important to understand that ‘self’ is not something that develops and remains static for the rest of your life. When we meet new people or experience new situations, we change and develop different ways of thinking, feeling and working. An awareness of this as a social care worker is necessary because you may find the relationship between you and your service user has the capacity to change how you both think about yourselves and each other. This is a two-way process and can lead to positive changes, but it can also raise some difficult questions about aspects of the self that have not previously been explored. This does not mean that all aspects of your self will inevitably change, but it acknowledges that personality is not something that is rigid and resistant to external influences. It is also important for service users to be aware of this in order to understand that they have agency and control over their lives. Reminding service users that people have the capacity to grow and, with the right supports in place, become the version of themselves they want to be is often related to the strengths-based approach that is used in social care work.

Practice Example 1

Self as open to change

Each year, as first-year students are deciding where to go on placement, I invite them to engage in a reflective exercise. I read the following statement: ‘I’m sure they’re grand, but I wouldn’t like to live next door to them’, and ask the students to think about the first person or group of people who popped into their head. Rather than share their answers, students are invited to reflect on where these thoughts come from and the possible impacts they may have on their practice and/or potential service users. Most students acknowledge that the view originates from preconceived ideas from family/friends or the media rather than personal experience or fact. Once we have discussed the possible consequences for their service users of such attitudes and/or biases, I encourage the students to challenge themselves to try at least one placement where they know people with similar issues or from those communities attend. The student should keep a journal to carefully monitor their views and/or values in relation to this person/people and observe if and how they change over time as the relationship develops. Students are also encouraged to reflect regularly and meaningfully on the possible impacts their values and beliefs may be having on their service users. (Lynda Monk has written a useful article to help students get started with journalling and highlights how it contributes to professional wellbeing (Monk 2011).) The majority of the time, students report being surprised by how fundamentally different they feel at the end of the placement and how their values have shifted through a combination of journalling/reflecting and the power of connection with service users. This proves that our selves are always changing and influenced by those we work with. The saying ‘If nothing changes, then nothing changes’ is pertinent here. Challenging assumptions and negative stereotypes will help students to develop healthier and more inclusive attitudes to those they work with.

2. Self as Contextual

According to González et al. (2004), identities can be enacted, constructed and/or ascribed by others and therefore are transient and develop within households, schools and communities. When addressing questions such as ‘Who are you?’ and ‘What are your values?’ people usually seek additional information in order to shape their answer. The context in which the question is asked is integral to the reflection that follows. Further questions must be considered, such as ‘Who is asking the question?’, ‘What is my relationship with them?’, ‘What impact will my answer have on the situation I am in or the people I am with?’ Having this contextual information is vital to the reflection and communication process. So too is the knowledge that it is impossible to separate ourselves from the communities, cultures, societies and times that we live in. Rose (2012) argues that if we are to reflect properly and learn about ourselves, it must be done within these contexts. At a macro level, this involves thinking about political systems, historical movements, physical environments, and cultural and economic contexts that shape our experiences. At a micro level, it is much more personal and requires reflection on the different relationships we share and the role we play within those. ‘The bigger and smaller picture are intimately interwoven in ways that are not always readily recognised, and this forms part of the exploration ahead’ (Rose 2012: 5).

Practice Example 2

Self as contextual

Imagine you are a student who holds strong religious beliefs and regularly practises your faith. You begin a practice placement where there is a service user who holds different and/or opposing beliefs to you but with the same conviction. Part of their care plan involves addressing their spiritual needs, which requires you to accompany them to their place of worship. How do you think you would feel about that? What would happen if you refused to do it because of your values? How do you think the service user would feel? Knowing that this is a scenario you are likely to come across in this context will help prepare you to examine your values in relation to it and explore possible impacts it may have on your relationship with the service user. Thus, when preparing for practice placement, it is vital to find out as much as possible about the agency before you begin. Who are the service users? What are the key issues they face? What are their needs and the interventions used to address these? What are the values associated with the agency? What is the funding situation? Where is the agency located in the wider context of care? These are all questions that it would be beneficial to have the answers to either prior to beginning or certainly within the first couple of weeks of starting. Having contextual information from a range of sources (perhaps agency websites, agency literature, e.g., annual reports/ leaflets, up-to-date research) places the student in a position where they can already identify how they might think, feel and act on their placement. Of course, there is no way of knowing for certain how you will react in different situations, but identifying aspects of the work that may be challenging or rewarding through reflecting on this material will provide a better sense of your ‘self’ in the context of your placement. ‘The more we can grasp of the context, the better our understanding of ourselves’ (Rose 2012: 5).

3. Self as Multiple

Many people believe that individuals have a ‘true’ or ‘core’ self that is associated with a consistent pattern of behaviours, thoughts and emotions. Relationships are valued because we value the consistency of knowing how someone will act based on previous encounters with them. From this viewpoint, when we encounter new people or situations, especially if there is a conflict of values, it can destabilise our sense of self because it requires us to figure out who we are when we are with them. Others believe we should end the quest to find our ‘true’ selves and instead embrace the multiplicity of selves and the richness and complexity it brings to the human experience (Schaffer 2006). The term ‘role’ is often used as a way of making sense of this concept. We draw upon these different selves or roles depending on the context we are in and the interactions we have. Katsiaficas et al. (2011) expand upon this notion and introduce the term ‘hyphenated selves’ by way of explaining identity construction in young people in shifting social and political contexts and in everyday interactions. For example, if I ask a person sitting before me in the classroom ‘Who are you?’, they might answer ‘A student’ because that is the identity they most associate with in that particular setting. If a stranger asked them the same question they might say ‘I am a parent’ or ‘I am captain of the football team.’ Each role will have certain characteristics and behaviours that are consistent with what is generally expected of that position. Esteban-Guitart and Moll (2014) put forward the idea of identity funds as a way of understanding how we can draw from the different selves we need in order to behave and/ or communicate effectively and appropriately in different situations. Think about the language you use when you talk to your friends versus when you talk to your parents, grandparents, a boss or small child. In general, it is unlikely the same words are used because we deem some language to be inappropriate or disrespectful to certain people, or at least that it might be interpreted that way. Regardless of the reason for not using that language, the awareness that it is not conducive to a positive outcome in an interaction requires the individual to draw on an alternative more appropriate self.

Practice Example 3

Self as multiple

It is essential to consider the multiplicity of self when establishing and maintaining boundaries in practice. Knowing that it is not only probable but necessary to display different aspects of ourselves when in a professional setting helps establish clear boundaries and appropriate ways of being. Consider the following scenario: You are a nineteen-year-old student on practice placement in a youth setting. It is Friday and you are stacking away chairs after the last session of the day. One of the young people, who is eighteen, asks if you have plans for the weekend. You reply that your favourite band is playing that evening, but you cannot go as all your friends have plans. The young person says that they also like that band and will go with you if you like. If you viewed the self as a unitary concept you might agree to go along with the service user as the facts are: (a) the person is over 18; (b) you like the band; and (c) you want to go – which all satisfy your personal self. However, through your training in college and awareness of policies relating to the agency, you should also be developing a ‘professional social care worker self’ or ‘social care identity’ and it is this self who will guide you in situations where your boundaries are tested. Drawing from this professional self and acting accordingly will also have a ripple effect on the service user, who will be influenced by your behaviour. Reminding the young person of professional boundaries will also help them to develop a suitable self for the youth club (a self who knows it is not appropriate to ask a worker out for a drink or to a concert).

Viewing the self as a unitary concept is particularly problematic in terms of the risks associated with service users internalising the labels assigned to them. In a study I conducted on the link between resilience, outcomes and children in foster care, I asked some of the care-leavers to comment on their identity. One young person replied, ‘growing up I was just a foster kid I guess (Douglas 2012). This description of himself was despite the fact he was also someone’s son, brother, friend, uncle, a hockey player and a good student, but his memories of the time did not reflect these multiple roles. The potential to label individuals and have their identity solely associated with that label is a risk that social care workers must be aware of. Labels such as ‘foster child’, ‘addict’, ‘homeless person’ and ‘autistic child’ can be internalised by the service user and can play an integral role in the construction of their identity or sense of self.

Viewing the self as a unitary concept is particularly problematic in terms of the risks associated with service users internalising the labels assigned to them. In a study I conducted on the link between resilience, outcomes and children in foster care, I asked some of the care-leavers to comment on their identity. One young person replied, ‘growing up I was just a foster kid I guess (Douglas 2012). This description of himself was despite the fact he was also someone’s son, brother, friend, uncle, a hockey player and a good student, but his memories of the time did not reflect these multiple roles. The potential to label individuals and have their identity solely associated with that label is a risk that social care workers must be aware of. Labels such as ‘foster child’, ‘addict’, ‘homeless person’ and ‘autistic child’ can be internalised by the service user and can play an integral role in the construction of their identity or sense of self.

4. No Self without Other

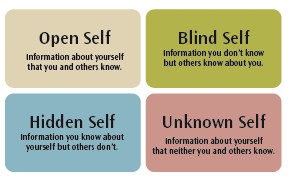

The proficiency that this chapter is focusing on is proficiency 22 (Domain 1): ‘be able to evaluate the effect of their own characteristics, values and practice on interactions with service users and be able to critically reflect on this to improve practice’. The final characteristic in Rose’s (2012) typology that is useful to consider in order to be competent in this area is that there can be no self without other. Rose uses the example that every single baby is born into particular social groupings based on their family, class, society, race and culture. All these factors contribute to the individual’s value system and understanding of who they are and who they ought to be according to a learned set of norms and rules. When we encounter individuals or groups with different values or priorities from our own, we can sometimes view them as less developed or less important. This is where the significance of critical reflection becomes apparent. If a social care worker is working with an individual from a different culture or with different priorities, they must ensure they are actively reflecting on what impact any conflict of values may be having on the service user, on themselves and, most important, on the practice. Although reflection on the self is often a personal exercise it relies on thinking about others too. To become self-aware requires the individual to be aware of others who are and have been instrumental in their lives. It is through reflecting on these interactions and relationships with others that a greater sense of self emerges. Giddens (1 991) notes this as ‘the reflexive nature of self-identity’ which is consistently revised according to life events, circumstances and interactions. Reflecting critically on who we are through our own and other people’s eyes is one of the key principles of the Johari window method. This is a simple yet effective tool that incorporates similar concepts of self as laid out thus far in this chapter. Fisher-Yoshida (2003) offers an interesting discussion on the use of the Johari window in becoming self-aware and attuned to the role individuals (influenced by their values) play in the co-construction of conflict. It also explores other methods useful for the critically reflective social care worker.

Practice Example 4

No self without other

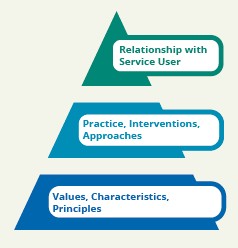

The pyramid below highlights how our personal and professional values often influence the interventions we use, how we approach our practice and how this in turn impacts on the relationship with the service user.

As you have undoubtedly read in many other chapters of this book, the foundations of social care work are based on the relationship between service user and social care worker. It is important then to engage in self-reflection regarding values and their possible impacts on the relationship. Accurately interpreting and assessing the values of service users is an equally important activity that is central to social care work, but it is something that we don’t always get right. One example of this comes from my 2011 research on outcomes and foster care. Young people (in and from foster care) and professional stakeholders (foster carers and social workers) were asked to list what they felt were indicators of successful outcomes for young people in foster care.

All the young people (n=8) referred in some way to feeling ‘happy’ in their answers. Contrastingly, all the professionals (n=87) listed ‘doing well in education’ as their number one or number two indicator of a successful outcome. The implication here is that the professionals placed a strong value on education and therefore interventions designed were often associated with improving educational engagement and attainment. The young people also mentioned education as an indicator of success, but given the traumatic background many of them had lived through, they felt that interventions should also be aimed at celebrating other definitions of success, such as a young person feeling genuinely happy. During the follow-up interviews with young people, I asked them about this and the consensus was not that they did not value education or wish to attain certain levels of education but the majority felt that if they were happy then it would increase their confidence and therefore the likelihood of wanting to further their education.

TASK 1

Interpretation of values

This exercise will help you to assess your own value system and to examine how your values compare with others’. It will also highlight the importance of language, interpretation and experience when reflecting on the possible impact values can have on practice.

Values for discussion: Achievement, Fame, Family, Freedom to Express Opinions, Friendships, Helping other People, Intellectual Status, Keeping Ireland Irish, Looking out for Number One, Religion, Truth, Wealth.

(Note to Facilitator: some of these values have been deliberately phrased in ways that are open to interpretation and to prompt discussion. The facilitator should change or adapt the particular set of values according to needs. This exercise works best as a visual piece, so I recommend printing each value on an A4 page and getting students/ members of the group to lay out the different lists. Halfway through the exercise the groups can walk around and look at how other groups are doing. If they decide to change the order of their list as a result of this, a discussion on how easily influenced we can be by others might be useful.)

- Instructions

Look at the list of values and think about how important each one is to you. List the values in order of importance. Think about what each one might mean and why you are putting it in a particular place. How influential are your previous experiences and/or relationships to this process? - In groups of four or five, agree on the overall order of the list and place in a way that is visual to all (on the floor or desks depending on space available). Everyone must agree on the order, and values cannot be placed side by side. Generate discussion on what the different value statements might mean and how easy or difficult it is to come to an agreement on where the different statements should go.

- As a group, reflect on how decisions were made. Were there any disagreements? If so, what were the reasons for this? What were the statements that groups found easy to place? Why? What were the statements that groups struggled to agree on? Why?

- Think about how these values might apply to social care practice. What impact might the value you put on any particular statement have on your relationship with service users? What would happen if you and the service user had conflicting values about certain issues?

Personal Values

Now that you have an understanding of how presentations of the self emerge through relationships, interactions and values, let’s take a look at how you can analyse your own values. In my years as a personal and professional development lecturer and, more recently, a Year 1 tutor, I have had many opportunities to chat with students regarding their motivations for doing the course and ultimately becoming a social care worker. What is apparent is that most of these students’ decisions come from a place of personal experience that is now rooted in their personal value system. The values of wanting to help vulnerable people, celebrate diversity, reduce inequality and be part of a team that supports individuals and groups to reach their full potential are often cited as being central to the decision- making process. These values are valid and in line with the professional values we strive to promote in social care work.

However, what students sometimes struggle with are the more personal values that can influence how we think and feel about certain situations. Once we start to peel back the layers of meaning and interpretations associated with aspects of life that hold varying degrees of importance to different people, the impact of personal experience in shaping those values becomes clearer. Let’s look at the example of family. Most students cite family as being the most important factor in their lives and the thing they most value or hold dear. The reasons for this are often related to the feelings of belonging, security and support that being part of a family often affords. However, if we look at the family situations of some of the vulnerable people who avail of social care services, this definition often does not apply to the same degree. For some individuals, the mention of family conjures up feelings of stress, loss or rejection. It is important for students to reflect on how their value on family may differ from that of their service users and any impact this may have. If a social care worker has a strong connection to their family and believes that ‘family should stick together’ there might be a temptation to allow this belief to impact on their relationship with a service user. Someone who holds this belief may, for example, struggle when working with a parent whose child is in the care of the state because of neglect or inability to cope.

Non-judgemental practice requires individuals to consistently examine any preconceived ideas, biases or past experiences that may be affecting the relationship and approach taken with the service user.

TASK 2

- Using the template provided at https://wehavekids.com/family-relationships/ find-create-family-crest-coat-of-arms-heraldry or https://www.therapistaid. com/therapy-worksheet/coat-of-arms-family-crest.

- Design a crest that identifies the people, beliefs, attitudes and things that are most important to you in your life, now and in the past, and that contribute to your sense of self.

- You can use words, quotes/lyrics, draw pictures, use collage or other creative methods. This is a personal exercise for you so you should use methods that make most sense to you.

- Reflect on why these things are important to you and where they come from. What have been the influences/experiences in your life to bring you to this point?

- Think about the following social care settings: homeless services; intellectual disabilities; residential care for young people; and members of the Traveller community. Do you think your values would be similar or different? What positive points/challenges might this have on your relationship with that person/people?

References

Douglas, D. (2012) Fostering Resilience: An Exploration of the Link between Resilience, Outcomes and Foster Care in Ireland. MA thesis: unpublished.

Esteban-Guitart, E. and Moll, L. (2014) ‘Funds of identity: A new concept based on the funds of knowledge approach’, Culture and Psychology 20(1): 31-48. Available at: <https://www.researchgate. net/publication/262637825_Funds_of_Identity_A_new_concept_based_on_the_Funds_of_Knowledge_ approach>.

Fisher-Yoshida, B. (2003) ‘Self-awareness and the co-construction of conflict’, Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation & Management 14(4): 169-82. Available at: <https://www.schillingcts. com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Self-Awareness-and-the-Co-construction-of-Conflict.pdf>

Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-identity. London: Stanford University Press.

González, N., Moll, L. and Amanti, C. (eds) (2004) Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Katsiaficas, D., Futch, V., Fine, M. and Sirin, S. (2011) ‘Everyday hyphens: Exploring youth identities with methodological and analytic pluralism’, Qualitative Research in Psychology 8: 120-39.

Kidd, W. and Teagle, A. (2012) Culture and Identity (2nd edn). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Monk, L. (2011) ‘Reflective Journal Writing for Social Worker Well-Being’, Self-Care Perspectives, September. Available at: <https://bcasw.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Reflective-Journal- Writing-H1.pdf>.

Rose, C. (2012) Self Awareness and Personal Development: Resources for Psychotherapists and Counsellors. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schaffer, H.R. (2006) Key Concepts in Developmental Psychology. London: Sage.

Zimba, R.F. (2002) ‘Indigenous Conceptions of Childhood Development and Social Realities in Southern Africa’ in H. Keller, Y.P. Poortinga and A. Scholmerish (eds.), Between Cultures and Biology: Perspectives on Ontogenetic Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.