Chapter 32 – Maeve Dempsey and Collie Patton (D2SOP9)

Domain 2 Standard of Proficiency 9

Be able to express professional, informed and considered opinions to service users, health professionals and others, e.g. carers, relatives, in varied practice settings and contexts and within the boundaries of confidentiality.

|

KEY TERMS Professional boundaries Communicating informed opinion Professional and ethical communication Boundaries of confidentiality Davidson’s Professional Relationship Continuum

|

Social care is … a relationship-based practice characterised by the dynamic and complex needs of vulnerable individuals within society. The role of the social care worker is to support and respond in a manner informed by knowledge and best practice, tailored to the individual’s identified needs, while being aligned to ethics, standards and engaged in accountable and reflective practice that is both respectful and boundaried towards the individual. By its very nature, care and support permeates social care relationships, which have the capacity to become a pathway and catalyst towards positive change. |

There are four other relevant proficiencies in the Standards of Proficiency for Social Care Workers (SCWRB 2017), outlined in the table below. This chapter focuses explicitly on the boundaries of confidentiality.

|

Domain |

Chapter in this book |

Focus on the Relationship |

|

D1 SOP10 (2017: 4) |

CH 10 by Anthony Corcoran |

Understand and respect the confidentiality of service users |

|

D1 SOP11 (2017: 4) |

CH 11 by Noelle Reilly |

Understand confidentiality in the context of the team setting |

|

D1 SOP12 (2017: 4) |

CH12 by Maria Ronan |

Understand and be able to apply the limits of the concept of confidentiality |

|

D1 SOP14 (2017: 4) |

CH14 by Teresa Brown and Margaret Fingleton |

Recognise and manage the potential conflict that can arise between confidentiality and whistle-blowing |

TASK 1

Please read Chapters 10, 11, 12 and 14 and answer the following questions: What is confidentiality? From your experience, are there limitations or situational contexts associated with confidentiality?

Defining Boundaries

Boundaries are ‘the limits that allow for a safe connection based on the client’s needs’ (Peterson 1992: 74) and are also the limits we set in relationships that allow us to protect ourselves. Through self-awareness, we develop clarity and insight into what is acceptable and unacceptable to us as individuals in terms of our boundaries, both personally and professionally. The concern about appropriate boundaries is, at least in part, a concern about the effects of the power differential between client and professional, recognising that we are working at a deep level with vulnerable individuals and thus there is a risk of boundary violations (Dietz & Thompson 2004). It is our responsibility to ensure that the support and care we provide to vulnerable individuals does not further disenfranchise or disempower them.

From a self-care perspective, social care work can be challenging and practitioners are frequently exposed to highly stressful and emotive situations. Consequently, maintaining strong and clear professional boundaries allows us to manage ourselves and regulate our emotions to ensure we are operating in a safe and ethical manner, cognisant of the limitations and boundaries of our role.

Professional Boundaries in Social Care

The relationship between social care practitioner and client is the central component in meaningful and effective social care work. How this relationship develops and functions is of significance when understanding the importance of boundaries and the limitations of confidentiality. In many ways, this relationship is born from an imposed and artificial situation and is characterised by a distinct imbalance of powers. This is inevitable because the worker’s role, influence, authority and access to confidential and sensitive information pertaining to the client and the client’s needs guide the relationship. The journey for both social care worker and client towards developing this relationship to a therapeutic one requires trust, effective communication, empathy and unconditional positive regard on the part of the social care worker. It also requires time and commitment. During this process, like any relationship, there is a ‘getting to know you’ stage which involves sharing information, often personal and significant to the client. It is at this stage that the foundations of clear and professional boundaries are laid, and the onus to both establish and maintain those boundaries must fall to the social care worker. This is not always an easy task and, in recognition of the dynamic and complex lives of clients, social care workers are often faced with ethical grey areas that challenge their professional boundaries and can result in lines being crossed. The context, the needs of the individual, the role of the social care worker, and the potential for misinterpretation are significant factors in understanding what constitutes balanced and boundaried practice.

TASK 2

Think about: Where do we draw the boundary between personal and professional relationships? How should social care workers present themselvesto service users?

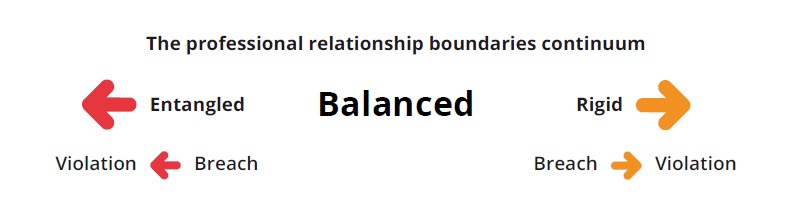

Davidson’s Professional Relationship Boundaries Continuum

A useful model for understanding and exploring appropriate professional boundaries is Davidson’s (2004) professional relationship boundaries continuum, a conceptual framework that encourages social care workers to engage critically with the complex relationships that exist with clients, between professionals, and subsequently identify boundary violations, increase self- awareness and critical reflective practice and initiate prevention strategies. Davidson (2004) provides both a point of reference and a common language for discussing the actions, choices and processes related to the boundaries of human service providers’ professional relationships.

According to Davidson (2009: np), ‘an individual who has an authentic and caring manner while maintaining clear boundaries is demonstrating balanced boundaries … They actively use professional judgment, consistently apply self-reflection skills, and are intentionally accountable to other professionals … Professionals with entangled professional boundaries are consistently over-involved in the lives of the clients they serve. They invest more of their time, emotional energy or favour in these relationships than in others, and they meet their own emotional, social, or physical needs through the relationship at the client’s expense.’

The significance of this framework as a ‘continuum’ acknowledges movement, progression and stages that are not clearly delineated. Therefore we can conclude that our boundaries have the capacity to change, are not concrete and can both progress and regress. In order to prevent regression to entangled boundary violations or rigidity in approach, and to ensure social care workers are practising with balanced boundaries, the topic of boundaries needs to be consistently on the agenda in team meetings and in supervision and should feature consistently within our own reflective practice. Research reflects that the more honest and open the communication between practitioners, the less likely it is that clients’ boundaries will be crossed (Thompson et al. 1995).

TASK 3

Using the Davidson professional relationship boundaries continuum (2004), describe and reflect on a recent experience in which you felt your professional boundaries were challenged. What insights and awareness have you in relation to what influences or impacts your boundaries?

Ethical and Professional Communication

The concept of relationship-based practice (RBP) has, at its core, the centrality of relationships and reciprocity in professional helping relationships (Mulkeen 2020). Acknowledging that the therapeutic relationship is at the core of social care practice, it would make sense that communication, an ability to express oneself appropriately and succinctly as a professional, is key to developing relationships between practitioner and client, and their families, but also between practitioners and other professionals. Language is a medium for communication, whether through words, images or symbols, and should be used appropriately to facilitate understanding. Furthermore, having a shared and common language and terminology is imperative for relevant and accurate record-keeping and communication between teams and disciplines. In all contexts, ethical and professional communication must be underpinned by respect and integrity towards freedom of expression, alternative perspectives and views, and the ability to tolerate dissent. To respond professionally, social care workers should take the time to understand and respect the contributions of others and subsequently evaluate for context. This means utilising silence skilfully as a means for essential space for thinking and reflection; asking questions to obtain clarity and stimulate thinking; and observing to comprehend non-verbal forms of communication, formulate hypotheses about what is happening and test the reliability of our perceptions against those of other individuals and other information available (Trevithick 2005: 121-2). In doing this, we are creating and promoting an environment conducive to effective and professional communication that allows for informed and effective decision-making by all parties. Practically speaking, this involves the social care worker understanding the communication needs of the individual they are engaging with, meeting them at their level, and ensuring that they suitably express informed opinions in a manner that is clear, succinct and appropriate. Avoiding jargon, using suitable and clear vocabulary, adopting a communication style that is inclusive and encompasses the entirety of expression, including verbal and non-verbal interaction, is key to a social care worker effectively communicating in a variety of settings and contexts.

Communication facilitates collaborative practice between professionals in social care practice. Deviation from this can result in the needs of service users and families not being met, and a failure to position the service user at the core of decision-making. Healthy communication takes place in ever-evolving social circumstances that are impacted by external influences and interpersonal factors. How social care practitioners and service users communicate with one another has a significant impact on the quality of care and on health outcomes such as service user satisfaction with care and overall improvement in health (Street 2003). Social care workers can often find themselves in a role where they are offering support to service users as part of a multi-disciplinary team. Indeed, these communications take place between social care workers and service users, family members, healthcare providers and others. Interpersonal health communication exchanges are part of a complex social system that influences health knowledge, behaviours and outcomes through information exchange (Nelson et al. 2004).

Case Study 1

Rosy is 35 years old and has a moderate intellectual disability and, as such, a reduced capacity to understand and process new situations and experiences. This is further complicated by literacy problems and communication problems. Rosy is a service user in a residential programme in which you work as a social care worker. Rosy’s parents are both engaged in her care and visit with Rosy regularly. A member of the residential social care team has noticed that Rosy has a lump on her side that is discoloured, and after they gave that information to the team, Rosy has had it explained to her that she would be going to the GP for a check-up. At this check-up the GP was sufficiently concerned about the lump that she has recommended Rosy go for a biopsy. As a social care worker, you have attended the appointment with the GP and will attend for the biopsy at the hospital. Rosy has noticed the lump and it has been causing her discomfort. The GP has explained to Rosy what is happening but is unsure how much of the situation Rosy has understood.

How can you support Rosy in understanding what is happening with her body and what the next steps are in her medical treatment?

Informed Opinions within Boundaries of Confidentiality

The boundaries of confidentiality are in place to keep the information of children, parents, carers and the members of staff confidential. It is the responsibility of all members of staff to keep the records of children and staff members, which contain personal information, safe and confidential.

The boundaries of confidentiality are in place to keep the information of children, parents, carers and the members of staff confidential. It is the responsibility of all members of staff to keep the records of children and staff members, which contain personal information, safe and confidential.

As previously stated, the relationship between social care worker and client is dominated by a power differential due to the social care worker’s access to sensitive information pertaining to the client, remuneration for their work, the relationship being led by the client’s needs and the influence the social care worker has in terms of decision-making. In most settings, the social care worker will be considered the expert. Clients will therefore believe you have the knowledge and experience to develop informed opinions and subsequently to give these opinions authority. How a social care worker develops this informed opinion is of relevance here. Information-gathering occurs not just through direct communication with service users and their families but through observation, and through attending both team and multidisciplinary meetings.

The social care worker can subsequently be found at an impasse whereby they are in receipt of knowledge or information relating to the client that has not directly been shared with them by the client. The human nature of the work does not allow us to disregard or forget this information, regardless of professional boundaries. We are therefore faced with recognising the importance of sharing information relating to our clients on a ‘need-to-know basis’. There is no scientific formula or direct theoretical guidance for making these decisions and so the social care worker takes the role of being discerning within the parameters of confidentiality, taking context, situation and time into consideration and ultimately their own professional intuition. Therefore, ethical decision-making is inevitably influenced by values, context and human fallibility.

It is in these situations that a scientific approach or formula may provide comfort and security to the worker, but in its absence the importance of the worker receiving support from their team and management when developing informed and considered opinions is imperative. Understandably, there is a culture of fear associated with making such informed decisions and the potential of negative professional repercussions due to a boomerang culture underpinned by accountability. What is meant by this is the acknowledgement that every decision made has the capacity to come back to the practitioner with significant professional implications. While accountability in practice is essential for quality and delivery of safe and effective care, it brings its own challenges and without adequate support can result in practitioners shying away from making informed and considered decisions.

An effective model of informed and shared decision-making that highlights the importance and benefits of inter-agency communication can be observed through Tusla’s Meitheal partnership approach. Meitheal is a targeted, co-ordinated intervention for families who do not meet the threshold for social work intervention but would benefit from a multi-agency approach where agencies can communicate and work together effectively and respond to families with a range of expertise, perspectives, knowledge and skills. The service user is at the centre of deliberations and considerations and is privy to and involved in the decision-making process throughout.

Boundaries of Confidentiality in Relation to Information that must be Shared

According to HIQA (2012), confidentiality in the health and social care context refers to the duty a practitioner has to safeguard information that has been entrusted to him or her by their service user. A duty of confidence arises when one person discloses information to another in circumstances where it is reasonable to expect that the information is held in confidence, such as between GP and patient (HIQA 2012). In general, it is essential that social care workers respect confidentiality and keep sensitive information pertaining to the service user confidential. Deviation from this can have a detrimental impact on the therapeutic relationship and result in a breakdown of trust. Generally, sharing confidential information, even between professionals or family members, should require informed consent from the client. If service users are confident that their information is being appropriately protected this increases trust between practitioner, service and client, which could result in the client feeling comfortable enough to share more information, ultimately improving safety and quality of care at an individual level (HIQA 2012).

However, there are exceptions and boundaries of confidentiality and the right to confidentiality is not absolute. Situations can arise relating to safeguarding of vulnerable individuals where confidentiality cannot be maintained. It is important to have transparent and detailed conversations informing clients about the limitations and boundaries of confidentiality from the beginning of the relationship. This clarity provides security to both worker and client and also ensures that the client is informed from the start in relation to conditions where limitations of confidentiality exist and that, even though social care workers are responsible for promoting and protecting confidentiality, situations exist where this cannot be maintained or guaranteed. The professional’s opinion about what to do in cases where confidentiality cannot be maintained is contingent on the degree and severity of the risk to the service user or another vulnerable party.

TASK 4

As a social care worker at the beginning of your career, can you think of a list of people who might appropriately influence your informed opinion-making process? Consider professional supports you would have access to and personal support networks the client may have.

Case Study 2

John is a 15-year-old boy who has been in the care of his maternal grandmother, Mary, since his mother passed away ten years ago. John’s father is incarcerated and John has never had any contact with him. John has had a turbulent couple of years and has struggled in terms of engagement with education and youth reach. Currently, John is not engaged with any form of education and has come to the attention of the police several times in the last year for anti-social behaviour. John’s placement with his grandmother has become unstable due to a combination of behavioural issues, anti-social behaviours and also the deterioration of his grandmother’s health. The Tusla Social Work team have suggested the possibility of John moving to a residential placement. When this has been mentioned to John he has responded vehemently against the idea as he wants to stay with his family. Mary is upset by this idea of John being ‘taken away’ as she feels responsible as John’s only family; however, Mary also accepts that she can no longer meet his needs in the home. As a social care worker in non-residential day services you have engaged with John over the past year and have developed a close relationship with the family. You are keen to support John during this difficult time. When you go to the house for your weekly session with John, Mary has asked you to explain what all of this means and what you think is the best option for John. Mary is upset that John is being ‘taken away’ but also acknowledges that she cannot meet his needs any more. The social work team have described to Mary the nature of residential care, but Mary’s understanding is that it is a form of incarceration. John is scared that he is being taken out of the family home and that fear is being expressed as anger.

Now consider the following questions:

What is your role as a social care worker in this situation? Consider effective and professional communication in your answer.

How would you respond to Mary’s questions about residential care in this context?

What is your understanding of this situation in terms of professional boundaries and boundaries of confidentiality?

Final Thoughts

From a practitioner’s perspective, it is imperative that we do not make promises pertaining to confidentiality that we cannot keep. If we do this we are in breach of and violating professional social care boundaries and subsequently putting our clients or other vulnerable individuals at risk. As previously stated, we frequently find ourselves in situations that call for careful ethical and professional decision-making and consideration of the SCWRB Codes of Professional Conduct and Ethics. Ensuring a commitment to our own professional boundaries will facilitate our ability to express professional, informed and considered opinions to service users, health professionals and others within the boundaries of confidentiality and will prevent us practising in an automatic, unthinking way. The juxtaposition that exists within practice that is concerned with maintaining boundaries, upholding rights of clients and the conduct and duties of social care workers compared to the narrative associated with choice, collaboration and care highlights the intricacies and human nature of social care work and the importance of understanding context, the complexity and sensitivity of the social care relationship and the need for a continued commitment to informed and knowledge-based practice.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

Understanding the context of the environment that students in the allied health professions will work in is key to effective practice education support (Mulholland et al. 2005). This context includes the interpersonal professional relationships that students develop within the placement environment. Students develop direct relationships with service users over time and through ongoing contact. However, students will also engage on an ad hoc basis with professionals from multi-disciplinary teams and personal support networks of these service users. Additionally, the interpersonal relationship and communication between the student and the practice educator plays an important role in the success of the placement learning experience (Mulholland et al. 2005). An understanding of social context is also important in navigating these tricky and complex interpersonal relationships (Ackerson & Viswanath 2009). Social context requires an understanding of the impact of macro-level environmental factors such as socioeconomic disparity, ethnicity and race, access to social networks, social support and social capital. Additionally, communication inequality should be considered when expressing professional, informed and considered opinions to service users, health professionals and carers or relatives. Communication inequality is defined as differences among social groups in the generations, distribution, manipulation of information at the population level and access to and ability to take advantage of information at the individual level (Viswanath & Ackerson 2011).

How can you prepare a student for these different roles and interpersonal relationships?

- Keep the topic of boundaries on the agenda for both individual supervision and team meetings. Our boundaries have the capacity to change throughout our career and should not just be a focus during student placement. Encourage discussion relating to professional boundaries and ethical scenarios.

- Ensure that students understand the boundaries and limitations of their role. Interpersonal relationships can get complicated in any setting and this can be even more apparent when working with vulnerable populations (Cooper 2012).

- When possible, allow students to engage with and/or observe the functionality of a multidisciplinary team and the sensitivities associated with boundaries of confidentiality in practice.

- Ensure that those with practical and recent experience of their professions take on the role of practice educators. Kilminster and Jolly (2000) recommend that practice educators have at least one year full-time post-registration experience prior to taking on the practice educator role.

- Placement educators should support students in their various forms of interpersonal communication such as information seeking, observation, uncertainty management, and stress buffering (Nelson et al. 2004).

- An effective practice educator needs good communication and interpersonal skills as well as practice proficiency and the ability to facilitate learning opportunities (Mullholland et al. 2005).

References

Ackerson, L. K. and Viswanath, K. (2009) ‘The social context of interpersonal communication and health’, Journal of Health Communication 14(S1): 5-17.

Banks, S. (2001) Ethics and Values in Social Work (2nd edn). London: BASW/Macmillan.

Cooper, F. (2012) Professional Boundaries in Social Work and Social Care: A Practical Guide to Understanding, Maintaining and Managing Your Professional Boundaries. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Davidson, J. C. (2004) ‘Professional relationship boundaries: A social work teaching module’, Social Work Education 24: 511-33.

Davidson, J. C. (2009) ‘Where do we draw the lines? Professional relationship boundaries and child and youth care practitioners’, CYC-Online issue 128, October. Available at <https://cyc-net.org/cyc-online/ cyconline-oct2009-davidson.html>.

Dietz, C. and Thompson, J. (2004) ‘Rethinking boundaries: Ethical dilemmas in the social worker-client relationship’, Journal of Progressive Human Services 15(2): 1-24.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2012) Guidance on Information Governance for Health and Social Care Services in Ireland. Dublin: HIQA.

Kilminster, S. M. and Jolly, B. C. (2000) ‘Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: A literature review’, Medical Education 34(10): 827-40.

Lehmann, P. and Coady, N. (eds) (2001) Theoretical Perspectives for Direct Social Work Practice: A Generalist-Eclectic Approach. New York: Springer.

Mulholland, J., Mallik, M., Moran, P., Scammell, J. and Turnock, C. (2005) ‘An Overview of the Nature of the Preparation of Practice Educators in Five Health Care Disciplines’, 6th Occasional Paper. London: Higher Education Academy: Health Sciences and Practice.

Mulkeen, M. (2020) ‘Care and the Standards of Proficiency for Social Care Workers’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies 20(2): 8-26.

NCI (National Cancer Institute) (2009) HINTS: Health Information and National Trends Survey. Available at <https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/Briefs/HINTS_Brief_14.pdf> [accessed 8 August 2021].

Nelson, D., Kreps, G., Hesse, B., Croyle, R., Willis, G., Arora, N., Rimer, B., Vish Viswanath, K., Weinstein, N. and Alden, S. (2004) ‘The health information national trends survey (HINTS): Development, design, and dissemination’, Journal of Health Communication 9(5): 443-60.

Peterson, M. R. (1992) At Personal Risk: Boundary Violations in Professional-Client Relationships. W.W. Norton & Co.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Thompson, P., Shapiro, M., Nielsen, L. and Peterson, M. (1995) ‘Supervision strategies to prevent sexual abuse by therapists and counsellors’ in B. Sanderson (ed), It’s never OK: A Handbook for Professionals on Sexual Exploitation by Counsellors and Therapists. Minneapolis: Minnesota Department of Corrections.

Trevithick, P. (2005) Social Work Skills: A Practice Handbook. London: Open University Press. Street, R. L., Jr (2003) ‘Interpersonal Communication Skills in Health Care Contexts’ in Handbook of Communication and Social Interaction Skills (pp. 927-52). New York: Routledge.

Viswanath, K. and Ackerson, L. K. (2011) ‘Race, ethnicity, language, social class, and health communication inequalities: a nationally-representative cross-sectional study’, PLOS One 6(1): e14550.

Wolvin, A.D. (2010) Listening and Human Communication in the 21st Century. UK: Wiley-Blackwell.