Chapter 34 – Gillian Larkin and Marian Connell (D2SOP11)

Domain 2 Standard of Proficiency 11

Understand and be able to discuss the principles of effective conflict management.

|

KEY TERMS The brain and emotions Emotional intelligence Self-awareness Conflict styles Principles of conflict management

|

Social Care work is about being in relationships with another, compassionately understanding their narrative to help and support them to flourish in all aspects of their lives |

This chapter will outline key principles of conflict management (Weinstein 2018), drawing on case vignettes from social care practice to help explore ways to manage conflict in social care settings. It will also explore emotions and concepts for developing your emotional intelligence and explore different conflict styles.

At its core, social care work is a relational-based practice (RBP) (Mulkeen 2020). Social care workers engage in relationships not only with service users but also with colleagues, and central to the development and maintenance of such relationships are the concepts of trust and respect, underpinned by the key theoretical framework from Rogers (1957) that includes empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard, and working from a human rights-based approach. However, RBP understands that people are rational and emotional beings. According to McGarr and Fingleton (2020), the primary tool at the social care worker’s disposal is the ‘self’, and the ‘self’ brings into these relationships all their experiences, values, beliefs, ideas, attitudes, feelings and behaviours. This view can be applied to the service user too, and when there are differences between people, conflict can occur. Higazee (2105: 1) posits conflict as a dynamic process that can be positive or negative, healthy or dysfunctional within a work environment. A common misunderstanding is that conflict is in some way a breakdown of normality, and is viewed as detrimental to those involved; however, conflict can lead to new ways of thinking, new practices and the growth and development of the people and the organisation (Everard et al. 2004).

In addition, social care workers play different roles, including care provider, advocator, educator, mentor and manager. These roles lead to various types of connection between social care workers and their service users, work colleagues and the wider multi-disciplinary team, including family members of clients, which increases the possibility of conflict within a social care environment. Keogh and Byrne (2016: 78) argue the need for ‘social care workers to engage in ongoing continued professional development and professional supervision’ to develop ‘skills in managing resistance and/or defensive responses’ that can contribute to conflict management.

Reflection

Why do social care students need to understand the principles of conflict management in a social care setting?

Before we explore what conflict is, take a moment to think about your experience of conflict in your home life. Are discussions viewed as an argument or an exchange of views? When there are disagreements, are they viewed as one person winning and one person losing? Do disagreements lead to silences? Fear? Anger? Rejection? Are disagreements avoided at all costs? Or do they lead to hearing another viewpoint, learning, and developing an ability to agree to differ?

How we view conflict and our experiences of conflict impact on how we engage in conflict; whether we see it as a battle or a learning experience, whether we view it as a winner and loser scenario, whether we embrace it or hide from it, or whether we see it as an opportunity for growth and development.

What is Conflict?

Conflict, defined by Doel and Kelly (2014: 21) ‘is a group dynamic that occurs when there is a difference of opinion, or a disagreement regarding the work or functioning of the group’. Conflict is unavoidable and can occur between professionals, between staff and service users and/or their family members; thus, having the skills to manage conflict is essential in social care work.

Conflict between Professionals

Conflict may emerge within the team that we are working in or in a multidisciplinary team that we may work alongside. Unlike other professions, social care work is unique in several ways which can contribute to conflict arising, including workers spending much of their working hours sharing a daily living space with staff teams (Share & Lalor 2009), and working a shift with staff members who have different values and beliefs. Thus, the social care worker may have to use their conflict resolution skills to de-escalate conflict arising between themselves and colleagues, or, if they are in a management role, between staff members.

Conflict with Service Users

Service users engage with social care services to have their needs met. Sometimes it is their choice; at other times, such as when service users are placed in residential or foster care, they may have had no choice in who they live with or where they live. Additionally, social care workers may engage with service users who have experienced abuse or neglect, present with behavioural, psychological and mental health problems, disability or addiction that contribute to poor emotional regulation (Keogh & Byrne 2016), which may contribute to incidences of conflict. Conflict resolution skills are essential in this context.

Types of conflict (Hizagee 2015)

While conflict can be healthy, Prendiville states that conflict is ‘an indication of competition between people which has surpassed a healthy level’ (2008: 65), and the figure above identifies different type of conflict that can be experienced (Higazee 2015). Scannell (2010) cites how unaddressed conflict can cause groups to collapse, while Jones et al. (2019) state that unresolved conflict in the workplace can cause low morale, poor performance, frequent absenteeism, and an increase in stress, combined with feelings of hostility, anxiety and anger.

Reflection

Reflect on the different types of conflict you have experienced working in a team. What was your emotional response to experiencing conflict?What strategies have you used to deal with conflict?Can you link your response to your previous experiences of conflict?

To support social care workers in engaging in conflict resolution, learning commences in their undergraduate training where students have multiple opportunities to engage in exploring their core values and beliefs through practice-based professional practice, workshops and practice placement. This learning advises social care students to seek resolutions to issues that emerge with their peers through identifying emerging triggers and developing clear communication patterns and active listening skills. Excellent critical reflection and self-awareness skills are a prerequisite in assisting with this process and students are encouraged to adopt a more open-minded view of conflict while utilising a compassionate approach to themselves and others. These topics are explored in more detail later in the chapter.

Why does Conflict Occur?

Research carried out by the nursing profession (Jones et al. 2019; Marquis & Huston 2012; Kleinman2004; Tomy 2000) highlight many reasons for conflict – limited resources; competition between professionals; variations in economic and professional values; reform; poorly defined roles and expectations; the ability to work as a team; interpersonal communication skills – and these can be equally applied to the social care profession.

Case Study 1

Monieka, aged 12, is living in a residential care home. Due to an acquired brain injury Monieka is unable to understand when she is full, resulting in overeating. A plan devised with a dietitian that involved structured meal plans, portion control and treats was implemented. When Monieka’s key worker was not working, staff in the unit brought Monieka out for treats to the tea shop and failed to adhere to her plan. At the team meeting, Anne, her key worker, was very cross and became red in the face and her heart raced when she talked about the plan not being adhered to. She became even more irritated when staff member Queen, raising her eyebrows, said it had only happened a couple of times and she was over-reacting. Paul, another staff member, said in a raised voice that he did not like his work to be analysed by staff not on duty.

- What is the cause of the conflict?

- Why did Anne respond as she did?

- What are the emotions emerging for the team?

- What are the reasons for the emotions?

What are Emotions?

According to Hockenbury and Hockenbury (2007), an emotion is a complex psychological state that involves three distinct components: a subjective experience; a physiological response; and a behavioural or expressive response. The first component, the subjective experience, relates to how we understand the emotion. To illustrate, the emotion of anger may translate into mild annoyance for one person to blinding rage for another. Emotions can also be mixed; for example, you might be excited and nervous about starting a new job, and these emotions can occur either together or separately. The physiological response relates to a physical reaction we experience when we have an emotion, e.g. sweaty palms, heart racing, shallow breathing, stomach unsettled, redness, trembling and so on. The behaviour response is the display of emotion, so the smile indicates happiness, the distorted face anger and so on.

We as social care workers spend a large part of our time interpreting the emotions of the service users we work with, but also of our colleagues. Equally, they are interpreting our emotions through our behaviour. Looking back to Case Study 1, we can ask: Why was Anne cross? Why was Queen dismissive of Anne’s feelings? Why did Paul raise his voice? By being able to correctly interpret the emotional displays of other people, we can respond appropriately. This is very important in conflict as to not understand yourself or others can lead to a negative emotional response due to amygdala activity.

The Brain and Emotions

Have you ever completely overreacted to a stressful situation/person/event? This is known as an emotional overload or, as coined by Goleman (1995), an amygdala hijack. You usually know you have had an emotional hijack if afterwards you or someone else asks, ‘What were you thinking?’ The usual response is ‘I wasn’t thinking’ and this would be correct.

Goleman (1995) argues that we usually process information through our cortex or ’thinking brain’; this is where logic (thought, judgement) occurs. However, there may be occasions where the ‘thinking brain’ is bypassed and signals are sent straight to the ‘emotional brain’ (limbic system). When this happens, there is an immediate, overwhelming emotional response disproportionate to the original event. The information is later relayed to higher brain regions that perform logic and decision-making processes, causing you to realise the inappropriateness of your original emotional response. In social care, there may be times when service users experience this kind of emotional overload, due to previous trauma and an inability to regulate their emotions. While social care students and workers tend not to experience this emotional overload, they can and do still experience an emotional response due to the activity of the amygdala. This can often be brought on by stress, fear, anxiety or anger and can result in conflict.

A stressful situation such as an approaching work deadline, service user/colleague difficulties, difficult tasks, role conflicts or emotional exhaustion can trigger a surge of stress hormones such as adrenaline, norepinephrine and cortisol that produce physiological changes such as the heart pounding, breathing quickening, muscles tensing, the appearance of beads of sweat and the ‘fight- or-flight’ response. This immediate emotional response was essential to early humans who were exposed to the constant threat of being killed or injured, so to increase survival, the fight-or-flight response evolved – an automatic response to physical danger that allows a person to react quickly without thinking.

In today’s world, you are unlikely to experience the same threats as our forefathers; however, you are likely to experience other kinds of threat, such as behaviours that challenge from service users or colleagues, people in in your daily life, and stress. When you sense danger is present, your amygdala automatically activates the fight-or-flight response. However, at the same time, the frontal lobes in your neo-cortex are processing the information to determine if danger really is present and, if so, the most logical response to it. When the threat is mild or moderate, the frontal lobes override the amygdala, and you respond in the most rational, appropriate way. However, when the threat is strong, the amygdala acts quickly. It may overpower the frontal lobes, automatically triggering the fight-or-flight response, which while not leading to a hijack of emotions, may lead to you reacting, resulting in negative behaviours such as raised voices, silence, avoidance, withdrawing or forcefulness, which impact the individual, the work environment and often the service users (Howard 2004).

Case Study 2

Sarah regularly cleans out the bedroom where staff stay when on a sleep-over. One day, she unknowingly throws out Martin’s toiletries, which he always leaves in the wardrobe. The next day, Martin discovers his toiletries are missing and erupts at Sarah. She responds by saying he should have clearly marked them as his belongings. They both leave this exchange feeling angry: Sarah feels under-appreciated for the work she does to clean the staff bedroom while Martin feels that no one respects his personal belongings.

- What is the cause of the conflict?

- What are the emotions emerging for Sarah and Martin?

- What has been left unsaid?

- How might this be resolved?

The Amygdala Response and Conflict

To gain a better understanding of what happens when we experience a threat or stress which can result in a fight-or-flight response, let’s look at Mary’s experience:

I was in a disagreement with a colleague who would not let me speak and constantly talked over me. I started to experience some physiological responses – my heart rate increased, my breathing became rapid, my body started to shake, and my voice was quivering. The active amygdala also immediately shuts down the neural pathway to my prefrontal cortex, so I become disoriented in the heated conversation. I was unable to make any kind of decision and could not see my colleague’s perspective, only mine. As my attention narrowed, I found I was only concerned with my safety, which in this instance was ‘I’m right and you’re wrong.’ Even though I knew my colleague well I could not remember a positive thing about her. [When our memory is compromised like this, we cannot recall something from the past that might help us calm down and instead we feel the amygdala indicating ‘Danger, react. Danger, protect. Danger, attack.’ When the amygdala is active, we cannot choose how we want to react because the old protective mechanism in the nervous system does it for us.] I shouted at my colleague to be quiet, which resulted in my colleague snapping back at me.

How to Manage Conflict

Key to managing conflict is not allowing our emotions drive us and making sure to respond and not react. In the example above, Mary allowed her emotions to take over and she reacted to her colleague, rather than responding. To manage conflict constructively, we need to be able to take charge of our emotions; in essence, we need to be able to override our automatic response to a threat or stress, as this will enable us to respond more appropriately.

Self-Awareness

Self-awareness is the exploration of our feelings, behaviours and thoughts. It is about recognising our skills and limitations and what impact they may have on others. It is also about recognising how external and internal events affect us and how we respond to them (Sharples 2013, cited in Stonehouse 2015: 1). Hayes (2004: 37) states that ‘the more we are aware of our values, beliefs and attitudes (and how these affect the assumptions we make about ourselves, others and the situations we encounter), the better equipped we will be to read the actual or potential behaviour of others and to construct effective courses of action in accordance with our reading.’

The Role of Emotional Intelligence (EI)

Emotional intelligence (E I) has been identified as an important component of self-awareness. EI has been noted as playing a significant role in positive workplace outcomes, and that includes managing conflict constructively (Schlaerth et al. 2013). EI has been defined as the individual’s ‘ability to motivate oneself and persist in the face of frustrations; to control impulses and delay gratification; to regulate one’s moods and keep distress from swamping the ability to think; to empathise and to hope’ (Goleman 1995: 34). Employees who have high levels of EI can accurately perceive, understand and appraise others’ emotions and build supportive networks.

They are also considered more interpersonally sensitive and understanding, warm, protective of others, less critical and deceitful, and more likely to turn to the better perceivers for advice and reassurance (Abas et al. 2012). Howe (2008: 12) notes that the emotionally intelligent worker understands that emotions affect behaviour, beliefs, perceptions, interpretations, thoughts and actions. If you have EI competence you will understand when a friend is feeling sad, when a colleague is angry, and you will understand when you are angry, sad, happy, scared. This knowledge will enable you to manage your emotions in a more positive way, which can reduce or eradicate conflict. Daniel Goleman’s (1996) model of EI comprises five realms: know your emotions, manage your emotions, motivate yourself, recognise and understand other people’s emotions, and manage relationships (others’ emotions), and these are broken into four quadrants as detailed in the diagram below.

Figure 1: Emotional intelligence model (Goleman 1998)

|

|

Recognition |

Regulation |

|

Personal Competence |

Self-Awareness

|

Self-Management

|

|

Social Competence |

Social Awareness

|

Relationship management

|

Becoming more self-aware through increased awareness of how we are perceived by others is important for our emotional development. For example, it allows us to reflect on the emotional impact of our behaviours on others and can enable us to change our behaviours and regulate our emotions more efficiently. In essence, EI competence can reduce conflict. Although conflict is a main function of work culture, it leads to desirable outcomes only if resolved constructively and managed effectively (Schlaerth et al. 2013). To think rationally and respond rather than react emotionally, we need to allow the information to reach the logical part of the brain and we can do this by becoming aware of our emotional triggers and learning to take a moment before reacting. This is achievable through having EI competence, and according to Salovey and Mayer (1990) EI competences can be learned and developed[1], so students and workers can cultivate skills that support conflict resolution.

Awareness about your Conflict Style

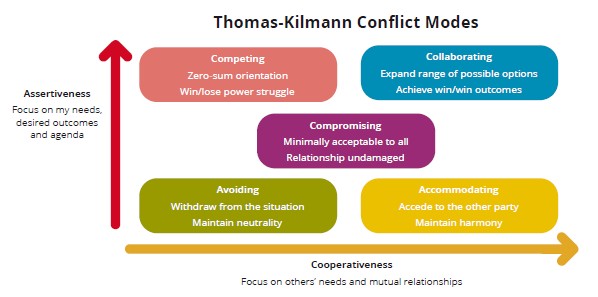

In addition to developing EI competence as a means of managing conflict constructively, an individual can learn what conflict style they have. The Thomas-Kilmann conflict mode instrument (TKI)[2] has been used successfully to help individuals in a variety of settings understand how different conflict styles affect personal and group dynamics. The TKI measures five ‘conflict-handling modes’, or ways of dealing with conflict: competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding and accommodating. These five modes can be described along two dimensions, assertiveness and co-operativeness. Assertiveness refers to the extent to which one tries to satisfy one’s own concerns, and co-operativeness refers to the extent to which one tries to satisfy the concerns of another person (Thomas & Kilmann 1974 2007).

Figure 2: Models of conflict management (Thomas & Kilmann 1976, cited in Darjan & Tomiță 2015)

In essence, the Thomas-Kilmann instrument (TKI) evaluates the behaviours of individuals in a conflict situation, how they react to certain situations and what is the most appropriate way to intervene (Ciorţă 2020). Those using the competing style demonstrate a high concern for self, which is evidenced by the need to maximise individual gain, even at the expense of others. At the other end is the collaborating style, which seeks to find solutions to meet the needs of all involved. The avoiding style disengages from conflict completely, demonstrating a low concern for self, while the accommodating style puts others’ needs before one’s own, thereby sacrificing self-interest. Those with a compromising style tend to stand between co-operativeness and assertiveness and make concessions so that a resolution can be found (Thomas & Kilmann 1974).

This model does not assume that individuals have only one style in managing conflict, but it does suggest that they may have a preferred style that they defer to in conflictual situations. Similarly, the model does not purport to state that only a collaborating style is always the most suitable, but rather different style may be relevant to different situations (Darjan & Tomiță 2015). For example, if an issue is not important and confronting may be time-consuming, the avoiding style may be best. However, if the issue is considered important, a competing style may be used. If we refer to Case Study 1, it could be assumed that Anne, the key worker, sees the issue as important and will use a competing style.

In helping to manage conflict effectively, it might help to ask the following questions, as the response may be influential when selecting a conflict style:

- How much do you value the person or the issue?

- Do you understand the consequences?

- Do you have the necessary time and energy to contribute?

Reflection

When conflict occurs, a social care student or worker has a choice – they can either react in a way that creates more conflict or respond in a way that create growth and harmony. According to Hocking (2006), when in conflict, professionals tend to use three styles to handle the situation – avoiding, forcing behaviours, and negotiating. This demonstrates that people usually deal with conflict in unhealthy ways, by either suppressing it or escalating the conflict. Suppression can include avoiding conflict, yielding during conflict, and withdrawing during conflict. Escalation can include forcing others, manipulation, being argumentative, threats. The use of reflection can help a student or worker to manage conflict in a healthy way.

Reflection is the purposeful rethinking of an action, the beliefs driving it and the resultant outcomes, to gain insight and understanding. Reflection enables the individual to step back and become critically aware of the assumptions, beliefs, values, hunches, biases and justifications that are pulling them into the conflict, and thereby provide insight through self-evaluation (Hocking 2006: 255). This reflection can occur prior to entering a conflict as well as throughout and after it, and it can help us avoid destructive scenarios, and create new communication patterns. While it can be a challenge to consider reflection when it feels like you are under threat or stress, the ability to pause and reflect does provide significant help. By taking the time to reflect, we are more likely to make some space within ourselves for understanding the actions, behaviours and viewpoints of ourselves and the other person.

Using the iceberg analogy, what we see in others is what is above the surface: tension, silence, withdrawal, stress, exhaustion, anger and disappointment. What we do not see is what is under the surface: fears, sadness, vulnerability, powerlessness, self-doubt and other beliefs that drive others to protect themselves[3] (University of Florida 2017). They equally only see what is above the surface in us too, and without self-awareness, EI and reflection, there is a propensity to view just the behaviours, which can result in conflict occurring.

Examples of Conflict in Social Care Practice

Case Study 3

Cathy is sitting in the office fuming. This is the third shift she has worked with Robert where she has had to make the dinner and he has done nothing to help. Cathy spoke to Mary and Princess about Robert not helping and they laughed and said, ‘Ah, Robert just comes to the table hungry, like the kids.’

What is the cause of the conflict? How might the conflict be resolved?

Case Study 4

Paul is Tommy’s key worker and is part of the care in review team. As Tommy is leaving the unit soon, discussions are ongoing as to where Tommy might live. Paul has been advocating for Tommy to go and live with his aunt as he has a good relationship with her and her family, and he will be near his mum, so building relationships will be possible. Tommy’s social worker, Kay, considers another residential unit the best option for Tommy, due to ongoing behavioural issues. Paul is aghast at this suggestion and engages in a very hostile manner with Kay. Voices are raised and Paul is asked to leave the meeting to calm down.

What do you think has caused this conflict?

Review it from Paul’s point of view. Review it from Kay’s point of view.

How might a resolution be found?

Whether you are a student, a social care worker or a manager it is important to understand how conflict arises, the causes of conflict, and the best ways to defuse conflict situations or to prevent them escalating. Conflict cannot always be avoided and while the above aspects of EI and knowing and understanding our conflict styles can help us to manage ourselves through self-development and awareness, we need to know how to manage conflict when it arises. Weinstein (2018) has articulated seven principles to effective conflict resolution, which will enable both an individual and an organisation to understand, discuss and resolve difficult situations.

Seven Principles of Conflict Management

The first principle is acknowledging the conflict. Often when conflict arises, an individual may worry about it, avoid the person they are having the conflict with, talk about the person behind their back and so on; however, this often leads to an increase in stress and anxiety about the issue and it can grow ‘bigger’, so it is best to accept that there is a conflict. Weinstein (2018) states that at this stage you may be acknowledging the conflict just to yourself, but it is important to do this as it allows you to reflect on what happened, what caused the conflict, how you feel; and this reflection can help to bring some clarity to the situation. Wachs (2008) describes this as assessing the situation, and it is preparation for the next principle, which is to take control of your response. Here our EI competencies can help. If we have good awareness of ourselves and our triggers, and understand the impact we have on others, we are likely to be able to respond in an appropriate way. Similarly, if we are sensitive to the other person, we are likely to understand what they are feeling and thinking, and their emotions. If action is required, it is best to think clearly about the conflict – the issue, your feelings, the choices available to you – before you respond. Often, it is safest to take a break as this allows you to step away and think logically rather than emotionally about the issue, and thereby avoid an emotional reaction, which can lead to consequences for you.

The next principle suggests that you construct a resolution using a conflict resolution framework (Weinstein 2018)[4]. In Weinstein’s framework there are two steps: the first is to prepare the conversation: this includes areas such as managing your physical and emotional response, writing down your initial fears, wants and needs, accepting responsibility for how you act and respond in the dialogue, ensuring that you have all the correct information, and identifying potential outcomes. In the second part of the framework, where you are talking to the other person, use active listening, paraphrase and summarise to ensure clarity, and be aware of the importance of body language. When responding, Wachs (2008) highlights the importance of using words appropriately so they do not hurt and emphasises speaking factually, using ‘I’ statements, using words such as ‘and’ and ‘instead’, rather than ‘but’, as the former can lead to constructive discussions, while the latter can lead to a defensive response. The Thomas-Kilmann framework is useful at this stage as our style is very important in the negotiation element of conflict.

The first three principles can lead to an effective resolution between parties: however, if resolution cannot be reached, principle four discusses managing the resolution via a third party. This person will generally have a vested interest in the matter being resolved and could be the unit manager, or a colleague of the two parties. Their role is nonetheless one of neutrality and of ensuring a satisfactory outcome.

Whether conflict is resolved by the parties or via a third party, Weinstein (2018) discusses the importance of creating a culture of early conflict resolution and this is principle five. This means creating a context in which all people in the organisation can accept their role in conflict and use such situations to increase learning. This does require a cultural shift within organisations: the use of policies and procedures, conflict training, identified ‘resolution agents’, coaches, mediators and a positive attitude towards conflict modelled from senior management supports the development of a new culture. When addressing conflict and ways to resolve it, the role of the manager or team leader in a social care setting cannot be undervalued. Part of their role is to contain and hold feelings that arise out of conflict and facilitate appropriate ways of expressing these emotions to bring about resolution for their team (Winnicott 1964; Bion 1959). This may be achieved through formal or informal supervision, peer support and mentoring, debriefing following a critical incident and open and honest discussion at team meetings.

Principle six is walking the walk. This is a particularly important part of conflict resolution. Weinstein (2018) posits that if we belong to a culture that accepts and engages with conflict, we need to take responsibility for our behaviour and conflicts at work and with the relationships we have with the people we engage with every day. How do we respond to conflict? Do we contribute to conflict? Are we willing to look at how we respond and react? To help us, Weinstein provides the CAN inventory, a quick personal check that we can run through daily to raise our Consciousness about the conflicts in our lives, Acknowledge them as potential triggers for change and growth and Now take action[5].

The final principle discussed by Weinstein (2018) is the necessity to engage the safety net. In some instances, informal resolution will not work, so it is important for the individual to know what polices are in place within the work environment should a resolution not be possible.

|

Summary

|

|

7 Principles of Conflict Management Principle 1: Acknowledge the conflict Principle 2: Control your response Principle 3: Construct a resolution Principle 4: Discuss managing the resolution via a third party Principle 5: Create a culture of early conflict resolution Principle 6: Walk the walk Principle 7: Engage in the safety net (Weinstein 2018)

|

TASK 1

Revisit Case Studies 3 and 4 and consider how you would apply Weinstein’s (2018) seven key principles to resolve the conflict emerging.

- Identify a situation where you recently experienced conflict.

- What was your emotional response?

- What differing viewpoints, values or beliefs created the conflict?

- How did you resolve the conflict?

- What could you have done differently?

- Identify skills and competencies that you drew on to resolve the conflict.

- What policies, legislation and support are in place to support you?

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Conflict Resolution for Students/Practice Educators/Managers

- Accept that conflict can be positive and can lead to growth and development.

- Take responsibility for your responses.

- Acknowledge conflict and ‘take a breath’ before responding.

- Use supervision as a means of reflecting on practice and learning and developing new skills in managing responses to difficult situations (Keogh & Byrne 2016).

- Engage in continuous professional development to understand self and emotional responses (Keogh & Byrne 2016).

- Create a culture of openness and commit to improving staff communication mechanisms and make discussions part of team meetings.

References

Abas, N., Surdick, R., Otto, K., Wood, S. and Budd, D. (2012) ‘Emotional intelligence and conflict management styles’, International Journal of Organizational Analysis 27(3). Available at <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267368228_Emotional_Intelligence_and_Conflict_ Management_Styles> [accessed 15 December 2020].

Bion, W.R. (1959) Experiences in Groups. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Cioarţă, I. (2020) ‘Dealing with conflicts in social work: A discussion on Thomas-Kilmann model applicability in social work’, Revista de Asistenta Sociala 2: 33-44.

Darjan, I. and Tomiță, M. (2014) ‘Helping Professionals:The bless and the Burden of Helping’, Second World Conference on Resilience: From Person to Society, Timisoara, May. Available at <https://www. researchgate.net/publication/273133270_Helping_professionals_-The_bless_and_the_burden_of_ helping> [accessed 15 December 2020].

Doel, M. and Kelly, T. (2014) A-Z of Groups and Group Work. UK: Macmillan International.

Everard, K., Morris, G. and Wilson, I. (2004) ‘Managing Conflict’ in Effective School Management (pp. 99-121). UK: Sage.

Goleman, D. (1996) Emotional Intelligence: Why it can Matter More than IQ. London: Bloomsbury.

Greene, A. (2017) ‘The role of self-awareness and reflection in social care practice’, Journal of Social Care 1(3).

Hayes, J. (2004) Interpersonal Skills at Work (2nd edn). London: Routledge.

Higazee, M. (2015) ‘Types and levels of conflicts experienced by nurses in the hospital settings’, Health Science Journal 9(6): 1-7.

Hockenbury, D. and Hockenbury, S.E. (2007) Discovering Psychology. New York: Worth Publishers. Hocking, B.A. (2006) ‘Using reflection to resolve conflict’, AORN Journal 84: 249-59.

Howard, D. (2004) ‘Stress, Relaxation and Rest’ in M. Mallik, C. Hall and D. Howard (eds), Nursing Knowledge and Practice: Foundations for Decision Making (2nd edn) (pp. 175-98). Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Howe, D. (2008) The Emotionally Intelligent Social Worker. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Jones, L., Harden, J., Radford, M. and McKenna, J. (2019) ‘Workplace conflict: Why it happens and how to manage it’, Nursing Times 115(3): 26-8.

Keogh, P. and Byrne, C. (2016) Crisis, Concern and Competency: A Study on Extent, Impact and Management of Workplace Violence and Assault on Social Care Workers. Dublin: Social Care Ireland.

Kleinman, C.S. (2004) ‘Leadership strategies in reducing staff nurse role conflict’, Nursing Administration 34: 322-4.

Lim, N. (2016) ‘Cultural differences in emotion: differences in emotional arousal level between the East and the West’, Integrative Medicine Research 5(2): 105-9.

McGarr, J. and Fingleton, M. (2020) ‘Reframing social care within the context of professional regulation: Towards an integrative framework for practice teaching within social care education’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies 20(2): Article 5.

Marquis, B.L. and Huston, C.J. (2012) Leadership Roles and Management Functions in Nursing: Theory and Application (7th edn). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Mulkeen, M. (2020) “Care and the Standards of Proficiency for Social Care Workers,” Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies: Vol. 20: Iss. 2, Article 4.

Prendiville, P. (2008) Developing Facilitation Skill: A Handbook for Group Facilitators (3rd edn). Available from https://www.academia.edu/37232772/Developing_Facilitation_Skills_A_Handbook_for_Group_ Facilitators.

Rogers, C. (1951) Client-Centred Therapy, Houghton Mifflin, New York.

Salovey, P. and Mayer, J.D. (1990) ‘Emotional intelligence’, Imagination, Cognition and Personality 9(3): 185-211.Scannell, M. (2010) The Big Book of Conflict Resolution Games. New York: McGraw Hill

Schlaerth, A., Ensari, N. and Christian, J. (2013) ‘A meta-analytical review of the relationship between emotional intelligence and leaders’ constructive conflict management’, Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 16: 126-36.

Share, P. and Lalor, K. (eds) (2009) Applied Social Care. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Stonehouse, D. (2015) ‘Self-awareness and the support worker‘, British Journal of Healthcare Assistants, 9(10): 479-81.

Thomas, K.W. and Kilmann, R.H. (1974, 2007) Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument. Mountain View, CA: Xicom.

Tomy, A.M. (2000) Guide to Nursing Management and Leadership. St Louis, MO: Mosby. University of Florida (2017) ‘Mastering Conflict through Self-awareness’. Available at <http://training. hr.ufl.edu/resources/LeadershipToolkit/job_aids/Mastering_Conflict_Through_Self_Awareness.pdf> [accessed 15 January 2021].

Wachs, S.R. (2008) ‘Put conflict resolution skills to work’, Journal of Oncology Practice 4(1): 37-40.

Weinstein, L. (2018) The 7 Principles of Conflict Resolution: How to Resolve Disputes, Defuse Difficult Situations and Reach Agreement. UK: Pearson.

Winnicott, D.W. (1964) The Child, the Family, and the Outside World. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Resources to discover more about EI, questionnaires and exercises to increase EI: https://positivepsychology.com/importance-of-emotional-intelligence/ https://positivepsychology.com/emotional-intelligence-skills/ https://positivepsychology.com/emotional-intelligence-frameworks/ ↵

- This Kilmann diagnostic website provides a range of resources, research and instrument to determine conflict styles: https://kilmanndiagnostics.com/overview-thomas-kilmann-conflict-mode-instrument-tki/ This document provides the instrument and interpretative report: http://www.lig360.com/assessments/tki/smp248248.pdf ↵

- This resource offers different questions you can ask to increase your knowledge of self and healthy conflict resolution: http://training.hr.ufl.edu/resources/LeadershipToolkit/job_aids/Mastering_Conflict_Through_Self_Awareness.pdf ↵

- Weinstein’s The 7 Principles of Conflict Resolution (2018) offers an in-depth appraisal of conflict and ways to resolution with a variety of activities and case studies to support understanding and development in this area. ↵

- For more detail on the CAN inventory go to: https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/the-7-principles/9781292220949/html/chapter-010.html. ↵