Chapter 40 – Tanya Turley and Diane Devine (D2SOP17)

Domain 2 Standard of Proficiency 17

Be able to recognise all behaviour, including challenging behaviour, as a form of communication and demonstrate an understanding of the underlying causes in order to apply appropriate strategies.

|

KEY TERMS Behaviour as communication Challenging behaviour Underlying causes of challenging behaviour Behavioural management planning Behaviour management Strategies for everyday activities

|

Social Care is … a human centred sector. Social Care is the recognition of the inherent value of human beings and the strength of the human spirit. It is working with and advocating for the most vulnerable in our society – with children, with adults, families, and communities. Social care is journeying on the life path of those who have entrusted us to listen to their stories. It is offering a holding environment when they are at their most exposed, helpless, defenceless and at risk. |

Social Care is also a place where we advocate and give a voice to the voiceless, it is a place where we encourage a sense of belonging, of non-judgement and of acceptance of the individual. It is a place where respect is integrated into everyday life and relationships are cherished. Social Care is the place where personal, life skills and inclusion are promoted – it is the place where personal growth happens. It is a place where compassion and empathy are integral for all to be reassured, they are of value, their lives have purpose and have and give meaning on a personal level and equally to their family and community. Social Care is a privileged position where we recognise vulnerability as central to our everyday work and are faced with the complexity of human life – it is the place on a moment-by- moment basis where we are cognizant, connected, genuine in our understanding that each vulnerable person’s life is important and matters.

TASK 1

Describe a recent experience where you felt you were not being heard or could not communicate your point. How did it make you feel and how did you react to or internalise this experience?

Behaviour as Communication

Everybody communicates through behaviour. Communication allows us to express our emotions and it empowers us to interact with each other. We are communicating something through our behaviour during every moment in every day, even if we are not aware of it. Behaviour is shaped by social norms and cultural expectations that are passed from person to person in our daily encounters as members of a family, a community and society (Eysenck 2002). Behaviour is our fundamental method of making our voices heard as human beings, through our verbal and non-verbal communication. Understanding how our service user may communicate emotions, thoughts or feelings, either verbally or non-verbally, through sounds and gestures, is central to our role as social care workers.

TASK 2

Essential Reading

Before you begin, please read the following:

- Eleanor Fitzmaurice, ‘Managing Challenging Behaviour’ (Chapter 13) inK. Lalor and P. Share (eds) (2013) Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland, Dublin: Gill Education.

- P. Keogh and C. Byrne (2016) Crisis, Concern and Complacency: A Study of the Extent, Impact and Management of Workplace Violence Experienced by Social Care Workers. Dublin: Social Care Ireland.

What is Challenging Behaviour in Social Care?

All behaviour is communication, and behaviour that was viewed as an act of disobedience or non- compliance with formal authority was described as ‘challenging behaviour’ (Fitzmaurice 2013). The ‘challenge’ was for the service to overcome in order to appropriately respond to the person’s complex needs. However, the term ‘challenge’ was interpreted as ‘problem behaviour’, a disruption, a form of hostility and potential violence (Fitzmaurice 2013). More and more professional groups are adopting alternative terms to describe challenging behaviour, such as ‘behaviour that challenges’ and ‘behaviour of concern’ (Chan et al. 2012). This in itself is constructive and its causes as it removes the negative and sometimes harmful label from the individual and places it on the behaviour. This can be very helpful as it supports professionals, family, peers and community in the person’s life to understand and appreciate the whole person and objectively work with them in using tools and strategies to manage and regulate the behaviour, thus recognising that the behaviour doesn’t define them as a person.

The main forms of challenging behaviour have been identified as aggressive behaviour, destructive behaviour, self injurious behaviour, destructiveness, hyperactivity and socially unacceptable behaviours (Emerson and Einfeld 2011: 6). The ways in which these behaviours are generally communicated are through conduct and actions that can be aggressive, assertive, passive and/or passive aggressive. Kissane and Guerin (2010) describe the complexities of ‘challenging behaviour’ and how the person can present with behaviours that can meet with one or more of the following criteria:

- The behaviour causes repeated injury (e.g. bruising, bleeding, tissue damage), or repeated risk of injury, to self or others (e.g. hitting, head butting, biting, scratching others, spitting, biting, punching, hair pulling, kicking) and/or causes damage to property (e.g. throwing objects and stealing) or is stereotyped behaviour (e.g. repetitive rocking or echolalia).

- The behaviour seriously limits the use of, or results in the person being denied access to, ordinary community facilities (e.g. inappropriate sexualised behaviour – public masturbation or groping).

- The behaviour causes significant management problems (intervention requires more than one member of staff for control and/or the behaviour causes daily disruption for the duration of at least one hour (Fitzmaurice 2013: 182).

While the above highlights behaviour that may be viewed within certain social care settings it is important to note that challenging behaviour is often not as pronounced as this. Indeed, it can be obvious or antagonistic behaviours (see Mark and Jess in the Case Study below) or more negative actions that are indirect and undermine the relationship (see Kelly’s Case Study – passive aggressive). Community Mental Health for Central Michigan (CMHCM 2012), in its training programme for managing crisis behaviours and de-escalation, describes challenging behaviour as conduct that can be considered under the following categories.

- Behaviour can be considered challenging when it affects an individual’s life in a negative way, or the behaviour has a vast bearing on how others relate to them. For example, if the person is ‘labelled’ as having a behavioural problem or being ‘difficult/challenging’.

- Behaviour can be considered challenging if:

- It causes actual harm – physical, psychological or emotional – to the individual or to others.

- It causes damage to property or belongings of self or others.

- It prevents the person from learning new skills, forming or maintaining relationships.

- It prevents the person from participating in social and recreational activities or if carrying out regular typical activities such as sports, drama, music, social groups necessitates risk management or a high degree of forward planning to carry out the activity (CMHCM 2012).

Task 3

Read the four case studies and answer the following questions: what do you Think is happening, how do you Feel about the event, what Behaviour is being expressed, and what Action will you take?

- Mark* (9 years old) returns from school, asks ‘Where are my headphones, you moved them, you took them, you bitch you robbed them, I’ll burn the place down, I’ll wreck it.’ He begins to shout and kick, and punches the door beside where you are sitting.

- Dean* (16 years), a young man who presents as sullen and often on edge, comes into the club. It’s his birthday and no one in his life has mentioned it. You start to sing (badly) ‘Happy Birthday’ and dance around with a chocolate muffin and candle while he responds, ‘Shut up, you’re thick and you can’t sing.’ One of the other lads starts to make negative comments about him – ‘He’s built like he’s six, not sixteen’ and Dean begins to get agitated and walks over to the young person who made the comment with fists clenched.

- Kelly* (38 years) refuses to answer your question about dinner, turns her back on you, stares at her phone, will not make eye contact, rocks back and forth while uttering something that you cannot hear. This is the third time this week this has happened when you speak with her. Then she makes a comment to another day service user who is nearby.

- Jess* (14 years) on late return to the house (emergency accommodation) from missing in care turns the radio on loudly in the kitchen, slams cupboard doors, opens and shuts presses, hums when you try to speak with her and begins constantly tapping the butter knife she removed from the drawer on the sideboard, ‘This would cut, you know, it would hurt.’

* Names and Details have been changed.

Underlying Causes of Challenging Behaviour

As social care workers, the very ‘challenge’ in challenging behaviour may be to remember that the person’s behaviour is a form of communication and at that moment they are trying to communicate something to us. According to Fitzmaurice (2013: 182) there are five elements to consider when developing a support plan for behaviours that challenge, which may help us as workers to understand what the person is communicating through the behaviour. These are biological, social, environmental, psychological and organisational.

Biological

This is behaviour as communication of pain or feelings of distress, anxiety, depression, neglect or frustration (Fitzmaurice 2013). From birth, infants are completely dependent on another person for their survival. Babies are born with three basic survival strategies – fight, flight, freeze responses – supported by the limbic system in the brain, which is triggered in reaction to different situations (Carter 1998). Through socialisation, upbringing and life experiences, people learn how to read situations, respond to people and control emotions and actions when in difficult situations or facing what may be perceived as confrontation. As adults, we keep the limbic system under control by rationalising and making judgements on the best outcome based on previous experiences. If an adult or child has experienced trauma, poor attachment or any experience that may have caused developmental delays, any new event that is perceived as stressful or challenging may cause the limbic system to become overwhelmed (Cairns 2002). In this case, the person or child begins to react without engaging the thinking part of the brain and responds with a fight, flight or freeze response (Carter 1998). Consider the Mark case study: What happened that day for Mark? Was there an incident at school? Is he tired or upset by something? At nine years old, is his biological system developed enough to manage profound emotion?

Social

This relates to adverse family situations, communication difficulties, boredom, maltreatment, seeking social interactions, the need for an element of control or independence, lack of advocacy, anxiety caused by lack of understanding in relation to community rules and appropriate behaviours, insensitivity of staff and services to the person’s wishes and needs. These can all impact on behaviour (Fitzmaurice 2013).

As human beings we have an innate need for relationship, a sense of belonging to, attachment with, a ‘container’ to hold our thoughts, feelings and emotions (Bion 1962). For service users, or people who are acting out in a challenging manner, developing new relationships is a difficult process. By forming relationships with social care workers, and other professionals, they risk opening themselves up to the potential of caring and being cared for and the possibility of being hurt. Closeness or proximity to other people can cause a sense of uncertainty, raise emotions and trigger a sense of danger. It is often easier to be defensive, to lash out, to attack than to admit or be able to consider why they feel this way. Paradoxically, the human connection or closeness that can aid our healing, support us in times of crisis or keep us safe from harm, can be the trigger for the challenging behaviour. Think of Jess (who has returned home). You welcome her back, say, ‘I am so relieved you’re safe. Are you okay? Let me make you something to eat – what can I get you?’ As a social care worker you want to ‘care’ – what happens when you try to display this care to Jess, if her previous experiences of relationships has been neglect, lack of care or inconsistent trust? How does she respond to you in this social situation and why?

Environmental

This relates to external stimuli, such as noise, lighting or change in routine, limits imposed by a structured setting, or an unsuitable physical environment. Winnicott (1965) highlighted the significance of a ‘facilitating environment’ in order to provide a safe space for children and young people to heal. Lack of a facilitating environment means the real work of healing, processing and building a relationship to soothe hurts cannot happen or becomes stuck. This does not necessarily mean that the environment must be physically perfect, but that at its core it has warmth, openness, a flexible structure ready to adapt to the needs to the persons accessing it or living within it (Ward & McMahon 1998). Things such as a favourite food on the shopping list or in the fridge, being able to incorporate people’s favourite colours in a bedroom or shared living space, and knowing the way a person takes their tea or coffee or if they prefer juice. Remember Kelly and her response to dinner? (What happens if you have been asked by six separate staff members over two days what you want to eat? What if no one remembers what you like or don’t like for meals, or you struggle to make even simple decisions? How would you respond?)

Psychological

Feelings of isolation and exclusion, feelings of loneliness, being devalued, labelled, disempowered, others’ limited expectations, not having someone to listen can all result in acting out and challenging behaviour (Fitzmaurice 1982).

Angry, violent, aggressive responses can be frightening, especially if the person – adult or child –is unaware of the source of their rage. The very behaviour that they are using to defend themselves against pain, or as a method of communication to say ‘hear me, see me, help me’ becomes the very behaviour that drives people further away and results in more loss and exclusion. Small steps or one piece at a time is the only way to build a foundation for significant work with vulnerable people. This is only going to transpire if we can hear beyond the words and actions to what they are really trying to convey. Dean saying ‘Shut up, you’re thick and you can’t sing’ could be perceived by the staff member as a personal insult at the thoughtfulness a birthday song and a muffin, if not viewed through the lens of a hurt, ignored child by those attuned to him. If unaware, the staff member could internalise Dean’s reaction as an insult, with the result that an effort will not be made again. With recognition of the child’s lived experience, a simple gesture could be viewed as a psychological hug or handshake – a feeling of being recognised, of being seen, and a special day valued. Furthermore, staff reminding the other young people in the club who made negative comments, ‘Ease up, guys, remember we don’t speak to each other like that here,’ or, ‘Well, if you want a song, just say so – I can serenade you too’ not only recognises Dean and his bruised emotions but also deflects the attention from him and the extra hurt that the comment may bring to him, unintended or not. Awareness by a professional of the psychological underpinning of aggressive behaviour in this situation is not defending negative reactions or a cure-all for the possible hurt, but it is a prompt to remind individuals of expectations, allowing the person who is spilling out to have space to recover, to not lose face in front of others but also to realise that they are truly seen and understood.

Organisational

Braye and Preston-Shoot (1995) highlighted reasons for difficult behaviour stemming from the organisation itself, they voiced concerns regarding service provision in itself been oppressive, examples in practice can be limits imposed by a structured setting, by an inadequate physical environment, by an over-controlled routine, and lack of choice and freedom. At the beginning of the chapter the question was posed – how did you feel if you were not able to use your voice, if you felt unheard? Did you want to react, to hide, to freeze, and have repeated conversation in your head about what you should do? Did you want to shout, feel frustrated or angry? If the problem is down to communication, this can frustrate the individual. Examples of these challenges could include difficulty in processing information that they are given – the information not being explained in a way that is specific and appropriate to the individual; not being able to express their feelings and difficulty in discussing issues they are worrying about; lack of control over their decisions and their independence. Unstructured time can be problematic, as can over-sensitivity or under-sensitivity to sensory stimuli.

Challenging behaviour is often a reaction to not being heard; it is a challenge not only to the staff and the service but to the organisation as a whole – to the system at large: ‘Hear me, I want you to listen, I want to make you understand!’ Van der Kolk (2015) outlined that in order to thrive we need relationships and opportunities to feel heard. We must move beyond the superficial conversation, but only if the place, people and system allow it. If the organisation, system or staff are felt or perceived as not understanding, not acknowledging, inflexible, the emotions, beliefs, thoughts held by a child, adolescent or adult, especially those who often feel at the mercy of a system, must escape somewhere. This fountain of emotion can no longer be held back and spills over in excessive anger, freezing or disengaging, or violent behaviour to self or others, as anger is often easier to experience than pain. You may see the organisational reasons that lead to the behaviour witnessed in Mark, Kelly and Jess (‘not my own home, different adults every day asking the same questions, can’t leave my things lying around, report keeping; everyone writes things down about me all the time – my whole life is a book’). Braye and Preston-Shoot (1995) advocate for ‘a balance of power’ in the relationship between staff and client – through self direction, respect and tolerance for the clients to participate in their own service design and delivery.

Behaviour Management Planning

The life of a vulnerable person in our care is not always an easy one and we need to recognise that all behaviour has a function, and there could be several reasons for it. The ability to see, understand and acknowledge behaviour is the opportunity to witness the child’s, adolescent’s or adult’s inner world. Furthermore, if we are attentive, we can acknowledge that the behaviour, whether conscious or unconscious, is describing the service user’s lived experience. To develop a relationship, and to offer structured supports and strategies to aid positive change, begins through learning from experiences of challenging behaviour. Managing behaviour, especially challenging and potentially aggressive behaviour, begins with a recognition of triggers and stress points. During relationship-building, look at what the person’s baseline (or everyday) behaviour is like, and what they experience as triggers (things that upset them, make them angry or that they struggle with). Listen to the service user when they are calm and work with them on how to avoid future overreactions. Examine de-escalation or support strategies to help them communicate what they need us to understand. Examples of de-escalation techniques include humour, taking time out or space alone, going for a walk, having someone to talk with, or using a punchbag when they feel heightened.

We need to remember that the individual should always be at the centre of all interventions, as one approach does not suit everyone. The most fundamental way of ensuring this is to ask the person what works or does not work for them at a time when they are calm or when they are able to explain in their own words. ‘What upsets you or makes you feel more angry or like running away?’; ‘Are there things that make it worse?’ Reflect for yourself what it feels like when you are angry and someone says to you, ‘Calm down’. Ask the question, ‘What makes you feel a bit better; do you like to be left alone or does it help to get out of the room/house?’ There is always an opportunity for learning; it may be just planting the seed within the person that YOU are the one who knows best, YOU have control over this, we want to support you in learning the skills to apply what you know.

Our aim should always be to improve the individual’s overall quality of life. As professionals in social care, it is our responsibility to protect the individual not only from any potential risks but also from themselves and others around them. By treating them with respect, using a measured response and working with them to understand that such behaviour is not acceptable, and a range of other appropriate communication methods are acceptable, you can ultimately help reduce flare-ups by helping them understand why they felt they need to act this way in the first place. Challenging behaviour can only realistically be handled with positive responses and a full understanding of the real cause behind it.

Behaviour Management Strategies

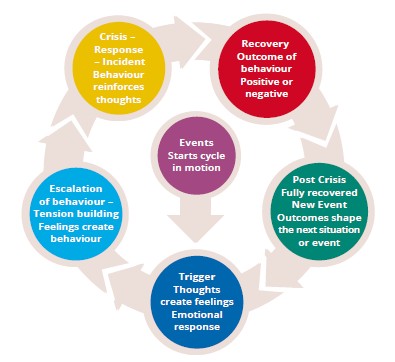

The employment of a specific approach to behaviour management by an organisation endeavours to make sure that the safest possible work practices are followed with positive consequences for the continued emotional and physical wellbeing of all the people in the organisation, staff and service users alike. But when we think about challenging behaviours and our experience of challenging behaviours, we recognise that behaviour generally occurs in a cycle which is known as the assault cycle (Kaplan & Wheeler 1983). It consists of: trigger; escalation; crisis; recovery; and post-crisis.

By using the assault cycle as an analytical tool it can support us in understanding antecedents and reasons for behaviours. It can support us develop a range of strategies to help reduce or remove the triggers that cause challenging behaviour and to teach more appropriate behaviours. It can also assist us in providing positive and negative reinforcement and consequences of behaviour that will encourage more appropriate responses. The Mansell Report in 1992 classified four essential features that would inform organisations on how to respond to challenging behaviour. These were ‘prevention, early detection, crisis management and specialised long term support’ (Fitzmaurice 2013: 183). This was the beginning of the development of a model of care that offers normalised, individualised and personalised support, which has been influential in the creation of the approaches and combined strategies used today.

It must be recognised that for the safety and wellbeing of all and in relation to positive role modelling within a service by staff it is never appropriate to ignore behaviour that is potentially abusive, destructive, threatening or dangerous. The decision to intervene and manage injurious behaviours requires professional judgement (Fitzmaurice 2013). The assault cycle (Kaplan & Wheeler 1983) as a system reflects the basic premise that underpins many of the therapeutic behaviour management programmes. The main ethos of all behaviour training programmes is not just avoiding and managing the situation but working with and developing life skills to aid individuals in regulating their behaviour that will have lifelong positive outcomes for those involved. There are a range of behaviour programmes for social care professionals to upskill and as part of their continuous professional development. Under the National Standards for Children’s Residential Centres (HIQA 2018) and the Policies and Procedures for Children’s Residential Centres (DoH 2009; TUSLA 2013). It is mandatory for all staff to complete behaviour management training, a full course initially and then a refresher course within one year.

Working with Challenging Behaviours

In working with and managing challenging behaviour, especially high-level chaotic or aggressive behavioural disturbance, social care workers may take the following into consideration:

- All behaviour has meaning: What is this behaviour trying to communicate? When Mark was kicking the door, saying you stole his headphones, what did he want to verbalise but was unable to? A difficult day at school? What does he feel is missing/has been taken from him? Does he need some individual attention? The Therapeutic Crisis Intervention Handbook (Cornell University 2012: 27) asks, ‘What does this person feel, need or want?’

- Timing: Always try to intervene at the escalation of the behaviour to offer strategies for the person to vent the emotion, discharge the feeling in a manageable way and return to baseline before the situation gets out of hand, e.g. ‘Mark, you sound and look really upset and angry, can you tell me why?’ or ‘Come on, will we go kick the ball in the garden and we can chat?’ Or in response to Dean, ‘I’m aiming for the next season of The Voice but while I’m practising my act will you take out the cups and we can have a cuppa to go with your birthday muffin?’Read the environment and the situation at hand: Early intervention can often stop escalation. Review the people, the situation and the environment. If the situation may calm down, leave it alone and do not interfere. All individuals need to find a way to regulate and manage differences with others. However, also read the room: was there an antecedent that has resulted in the person’s behaviour beginning to escalate, or is the person still becoming heightened, e.g. pacing, fidgeting, foot tapping, muttering under breath? (Think of Jess returning from being missing in care, the potential impact of her being reported missing, the possible consequences for her, fear of reprisal. This may need intervention to prevent the situation developing.) Choose the time, place and moment to intervene; the main focus is safety and aiding a return to baseline behaviour. Consequences for actions and process work can be done at a time and in a space that is right – which may not be right now. ‘Jess, it’s very late and we’re all tired. We can talk about this tomorrow – for now let’s get you sorted and get a good night’s rest, we’ll figure it out together tomorrow.’ If necessary, distance yourself physically from the situation. This is not an admission that you are not able to manage the situation, but being astute and intuitive enough as a social care worker to recognise that this is not the correct time. Active engagement around an emotive topic now may be more detrimental than helpful in the long term.

- Conscious use of self: Asking yourself ‘How do I feel now? What are my thoughts?’ might seem impractical when a situation is becoming difficult, but taking a second to check in with yourself may prevent a situation from becoming more uncontained (McDonnell 2010). As practitioners it is fundamental to be able to read our own internal responses to a situation, acknowledge our own emotions, reaffirm our ability to manage the situation and be aware enough to know when more support is required. Even though the content may be channelled at you, the motive behind it is not usually you. Instead, it is related to the person’s prior experiences and how something has resulted in them being triggered, and their inner child is reacting in the only way they know how – fight, flight, freeze. If we are not attuned to this, how might we respond to a distressed person? Our tone of voice might be too sharp if we are irritated or tired; we might interrupt, use too many words or name consequences because we feel threatened or anxious; we might blame the person for the consequences; our body language might be unhelpful, e.g. staring, showing defensiveness by crossing our arms, putting out our chest, raising our voice to make our point?

- Awareness of the value of relationship and the individual’s strengths, challenges, trigger points and baseline behaviours (Kemshall et al. 2013). Familiarise yourself with the individual’s crisis management plan (ICMP) or behavioural support plan. Consider which tool to use at that particular moment to allow the person time to pull back, to deflect the agitation or reduce tension, e.g. humour, just being present with, ignore, etc. With Kelly, you might ignore the interaction with the other resident and return to it at a later time, and use encouragement and humour – put on an apron, use the chef’s voice from Sesame Street or tell her dinner is going to be a game of ‘Come Dine with Me’ or the ‘Blind Taste Test’ – you cook and the young people must guess what it is, those who guess correctly winning a takeout night. Intuition might tell you that the individual may need particular attention at that moment but is seeking it in a negative way.

- Kinesthetics: Body language, eye contact. How you approach a situation, the tone of your voice, your language and body language are crucial factors in helping or hindering (McDonnell 2010). For example, ‘I want to talk with you’ could be construed as ‘trouble’; having other people around as an audience can impede the work. Visualise Kelly – she may feel that she cannot be seen to ‘give in’ to staff. Ask the second young person if you can have a moment with Kelly, sit beside or in proximity to her (being in front of a person can often be viewed as too confrontational), use a low, gentle tone of voice, make eye contact if possible, but vary eye contact (staring can be disconcerting), and ask open questions – ‘What’s happening at the moment?’ – or ‘door openers’ such as ‘What’s up?’ – which require more than a yes or no answer (Cornell University 2012).

- Ignore or redirect: On occasion a behaviour is best dealt with at that moment by the simple expedient of ignoring or redirecting it. You might choose not to engage Kelly at that particular moment in relation to her behaviour around dinner or you could offer alternatives, e.g. you will do ‘pick and mix’ for dinner, but does she want to get her chores done before or after the meal? With Jess you might say, ‘Well I’m sure it would hurt very much, Jess, getting cut with a knife, but imagine the blood – red is not my favourite colour’ or ‘ I’m going to have a toastie, would you like one? Would you butter the bread?’ or ‘It’s late now and you must be tired, we can chat about this in the morning.’ This is not ignoring the behaviour but offering space to rethink the situation as needed, and calming the environment; you can return to the event and reflect on it at another time when there is the opportunity to spend time processing the reasons for it, its impact, what could be amended (Briggs 2002).

- Distraction: Can you change rooms, or get some other activity going that will minimise the emotion in the situation and support the person to regulate? Diverting the individual’s attention elsewhere in the preliminary stages of a behaviour that challenges by focusing on other movements, environments, activities, can defuse tension. For example, with Jess: ‘Do you want to take a shower or get into some comfortable clothes?’; with Mark: ‘Come on, I’ll help you look for your earphones, I’m sorry they’re missing, but don’t worry, we’ll hunt them down’ (CMHCM 2012).

- Silence: Not every silence needs to be filled with noise, if appropriate, sit with the emotions, allow the person to vent and your presence alone will be enough. Sometimes people need time to process their thoughts or think out loud or have a sounding board. If needed, reassure the person that you are there and you are listening to them – ‘I am here for as long as you need.’

- Alternatives and directives: Many people, when caught up in emotion, become ‘stuck’ in the fight, flight, freeze loop. They may be unsure what to do or be unable to consider other rational alternatives to acting out or how to extract themselves from the situation. Consider what choices are available and what method best fits the person – remember, individuals are key. Some service users will respond to direct language, short, concise and direct, e.g. Dean – ‘Please move back from …’; Mark – ‘Please stop kicking the door.’ Other situations and persons may be best met with options – offering a choice but also giving back a sense of control. Offer limited choices; too many will add more turmoil, e.g. with Mark, ‘I can see you’re upset. We can do two things – one, let’s go look for the earphones together now; or two, come into the garden and we can figure this out together.’

- Compassionate movement: This is not a reinforcement of negative behaviour but a recognition of the person and their distress. Assess whether this is appropriate or could escalate the situation more. Any physical touch is dependent on your relationship, your experience of the young person and their history. Approach the person from the side, not the front, as it is less confrontational, sit down as opposed to standing when chatting with them. If the situation is between two young people, can you sit or stand between them as a buffer? A hand on the forearm or shoulder can be enough to say, ‘I’m here and I am holding you (metaphorically).’ Remember, physical touch is completely dependent on the person’s wishes and level of distress at the time. It should never be used when a person is moved beyond irritated and agitated and very heightened (Cornell University 2012).

As professionals in social care it is important to recognise that all attempts to manage challenging behaviour must happen in the context of duty of care to both the vulnerable people and the staff with whom we work. Management of challenging behaviour, whether it is mild, moderate or severe, must take into account the personal attributes of the vulnerable person based on a needs assessment of the physical and social environment in which the person’s care takes place. All challenging behaviour is communicative and happens within a social context: it always has meaning. As social care workers we need to always remember that the service user can be helpless and vulnerable to exploitation and harm, therefore special attention needs to be paid to managing respectfully and safely the challenging behaviour presented by the individual and understanding what they are trying to communicate to us. As social care workers we also need to acknowledge that the effects of working in crisis situations every day can be arduous and demanding. Continuous professional training, personal supports through a team system and reflection through professional supervision is vital in helping us to identify and cope with the personal and professional challenges implicit in this often highly stressful aspect of social care practice. By acknowledging our strengths and vulnerabilities and through mutual respect, planning effective, consistent strategies together will support us in working and responding appropriately and in respecting individual differences within our professional team and with people with challenging behaviour (Fitzmaurice 2013).

TASK 4

- Be a self-reflective social care practitioner. What behaviours are you at ease with? What behaviours challenge you most? Can you consider why?

- Review one previous event in relation to a difficult behaviour you experienced. How did you handle it? What went well or perhaps what did not? What could you do if it happened again?

- Be creative. Look at the interests of vulnerable individuals and recommend activities that are enjoyable that could be used as an antecedent to a behaviour.

- Choose a service user who has challenging behaviours and look at friendships. Recommend activities using a ‘buddy systems’ approach where s/he supports another service user in the activity or another service user supports them. Observe them together to see if they regulate their own behaviour or each other’s behaviour and identify if they find this behaviour management easier or less conflicting than with a staff member.

- Study the management approaches used by the organisation and examine how they are realised in the services Challenging Behaviour Policy. Make a time in the day where everyone within the service can sit down together to share a challenge or a pleasurable experience of their day and discuss how it made them feel.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

A founding requirement for the achievement of this proficiency is the student being able to recognise all behaviour, including challenging behaviour, as a form of communication and demonstrate an understanding of the underlying causes in order to apply appropriate strategies.

- To help a student comprehend behaviour as communication, ask them to describe a recent experience when they felt they were not heard or could not communicate their point, how it made them feel and how they reacted to this experience.

- Then encourage the student to talk with a service user about how they communicate their feelings to the staff and what type of communication method is the most beneficial to them in their lives. If the student is working with service users for whom verbal communication is challenging it might also be useful for them to talk to staff and gain assistance in adapting to the service users’ communication techniques.

As well as understanding that all behaviour is communication it is also important that the student has a level of self-awareness about what to them constitutes challenging behaviour.

- What are their own comfort limits in relation to experiencing or dealing with challenging behaviour? We must be aware of our own boundaries and limitations in order to support others to learn theirs.

- Additionally, for practice educators an intellectual understanding of challenging behaviours in social care and the main forms and multiple factors that underlie challenging behaviour is essential. If social care workers do not have a grasp of the root of behavior, we cannot anticipate the events that may be triggers.

Having the conversation and asking the student to explain it from a factual/theoretical experience first and then to give examples of challenging behaviors practically – where they observed it and how it was managed – will allow you to informally assess the link between the student’s understanding of challenging behaviour and their observations on the behaviour management strategies used by the organisation. Remember, because of the complexity of challenging behaviour and the professional judgement by staff on how a behaviour is managed, for example when a behaviour is ignored, redirected, averted or reported on for assessment by a specialised team, can be confusing, so you may need to guide the student through this multiplicity of decisions on challenging behaviour cases. If a deficit in the student’s understanding is identified, you can either direct them to review knowledge they encountered in their academic study or provide them with reading material associated with challenging behaviour. It is imperative that you provide a time frame in which you will follow up on the reading, thus creating a cyclical learning relationship between task ascription, task completion and professional development.

Once the student can converse about the multiple factors that underlie challenging behaviour and how it is used as a communicative mode, you can ask them to consider the challenging behaviour management method used within the service and the strategies they have observed staff use since beginning placement.

- You could ask the student to personally reflect on their concept of challenging behaviour and how it might inform or challenge their practice as a professional and the experience of the vulnerable service user. While potentially uncomfortable, it is important that this analysis happens so the student can use in-action reflection, thereby maximizing the opportunity for service user support, respect, safety and care.

- An aspect of professional practice the student needs to adapt to is the responsibility to adapt practice, so that service users experience a high level of support through the means of their individual communication methods.

- As the student grows in confidence it is important to encourage them to identify activities that could potentially support the prevention or aversion of a behavioral outburst and to discuss them with the key staff working with specific vulnerable individuals.

- Within supervision these opportunities could be considered in terms of viability and included in the service users’ personal behavioural plans or in the organizational strategy.

Part of analysing activities is to identify if they are feasible, useful and relevant to specific individuals – has the student observed and accurately interpreted the service user correctly?

- The student may provide suggestions and creative activities, but it is not the student’s responsibility to enact these activities.

- Ask the student to create a picture communication booklet with a service user (or group) that represents the service user’s interpretation of feelings and emotions when communication is acceptable and they feel heard or where they felt frustrated where they feel not listened to and misunderstood. The booklet should include activities that promote positive behaviour and that help with behavioural balance, and strategies to support or regulate the behaviour. This could be fruitful as a means of increasing the student’s awareness of the proficiency or a way to demonstrate their capacity to enact the proficiency.

References

Bion. W. (1962) Learning from Experience. London: Karnac Books.

Braye, S and Preston-Shoot, M (1995) Empowering Practice in Social Care. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Briggs, S. (2002) Working with Adolescents: A Contemporary Psychodynamic Approach. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. Cairns, K. (2002) Attachment, Trauma and Resilience: Therapeutic Caring for Children. London: British Adoption and Fostering Federation.

Carter, R. (1998) Mapping the Mind. Weidenfield Nicholson. Chan, J., Arnold, Samuel RC., Webber, Lynne S., Riches, Vivienne C and Parmenter, Trevor R (2012) Is it Time to Drop the Term Challenging Behaviour. Learning Disability Practice 15 (5): 36-38 [online] available at http://www.researchgate.net

CMHCM (Community Mental Health for Central Michigan) (2012) Positive Approaches to Challenging Behaviors, Non-aversive Techniques & Crisis Interventions https://www.cmhcm.org/userfiles/ filemanager/541/ (cmhcm.org) [accessed 29 December 2020]. Cornell University (2012) Therapeutic Crisis Intervention Handbook. Available https://rccp.cornell.edu/ downloads/TCI_7_SYSTEM%20BULLETIN.pdf” https://rccp.cornell.edu/downloads/TCI_7_SYSTEM%20 BULLETIN.pdf (accessed 3 January 2021)

DoH (Department of Health) (2009) Policies and Procedures for Children’s Residential Centres, HSE Dublin North East. Available at <https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/children/policies> [accessed 2 January 2021].

Emerson, Eric and Einfeld, Stewart L (2011) Challenging Behaviour 3rd ed. UK: Cambridge University Press Eysenck, M.W. (2002) Simply Psychology. Psychology Press.

Fitzmaurice, E. (2013) ‘Managing Challenging Behaviour’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (2013) Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill Education.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2018) National Standards for Children’s Residential Centres. Available at <https://www.hiqa.ie/reports-and-publications/standard/national-standards- childrens-residential-centres> [accessed 17 January 2021].

Kaplan, S.G. and Wheeler, E.G. (1983) ‘Survival skills for working with potentially violent clients’, Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, <<https://www.journals.sagepub.com>.

Kemshall, H., Wilkinson, B. and Baker, K. (2013) Working with Risk: Skills for Contemporary Social Work. Cambridge UK: Polity Press.

Keogh, P. and Byrne, C. (2016) Crisis, Concern and Complacency: A Study of the Extent, Impact and Management of Workplace Violence Experienced by Social Care Workers. Dublin: Social Care Ireland.

Kissane, S. and Guerin, S. (2010) ‘Meeting the Challenge of Challenging Behaviour’ (Paper 4). Dublin: National Disability Authority. Available at https://www.nda.ie.

McDonnell, A. (2010) Managing Aggressive Behaviour in Care Settings: Understanding and Applying Low Arousal Approaches. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

TUSLA – The National Standards for Protection and Welfare of Children and Family Services (July 2012),Dublin: Health and Safety Authority

van der Kolk, B. (2015) The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books.

Ward, A. and McMahon, L. (1998) Intuition is not Enough: Matching Learning with Practice in Therapeutic Childcare. Sussex: Routledge.

Winnicott, D.W (1965) The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment. London: Karnac Books.