Chapter 48 – Jacqui McCann (D3SOP8)

Domain 3 Standard of Proficiency 8

Be able to evaluate intervention plans using appropriate tools and recognised performance/ outcome measures along with service user responses to the interventions. Revise the plans as necessary and, where appropriate, in conjunction with the service user.

|

KEY TERMS Strengths-based approach Positive behaviour support Opportunity and support Hope Motivation and role modelling Reflective practice and learning

|

Social care is … a platform for providing care to adults and young people who need support to manage in their daily lives. It is the opportunity to enhance and develop an individual’s needs which can in turn promote positive experiences and outcomes. |

Social care practice has evolved to create many different pathways of working with individuals in their life space to respond to their care needs. At the forefront of this practice is a drive, not just to respond to these needs, but to ‘do better ‘and provide high-quality standards of care. In terms of the provision of residential care for young people in care in Ireland this drive to ‘do better’ has been led by the by the institutional scandals that demanded reform. Young people in care in Ireland, whether in foster, residential or special care, are united by the impact or effect of the trauma or abandonment that resulted in them being placed in care and the transitions between care placements that contribute to these effects.

In this chapter the provision of special care in Ireland as an intervention will be discussed along with the individual intervention plans that are adopted. Special care is a purpose-built secure facility for young people in care who are detained by a High Court order because they pose a risk to themselves or others. Special care is an intervention for young people who have experienced significant trauma and are presenting with extreme risk-taking and/or highly challenging behaviours. The chapter will also identify the core intervention plans that are designed and implemented to respond to the specific care planning needs of the young people. These include responding to risk; health and wellbeing; behavioural, therapeutic and relational needs. How the intervention plans are developed and reviewed will be explained, along with how the outcomes for the young people are measured.

The care system in Ireland has the unique role to provide for and respond to the needs of these young people at the fulcrum stage of their development ‘during their childhood’. This is a critical period of our lives that shapes our adulthood. Young people who are placed in care have a complexity of needs. Alongside their primary emotional, physical, social and educational care needs, young people who have been placed in residential care, and specifically special care, also require intensive support and intervention regarding risks associated with their behaviour. But how do we identify what they need and what to prioritise? How do we intervene and provide the care they need? How do we identify the outcome and impact? How can we keep them safe from harm?

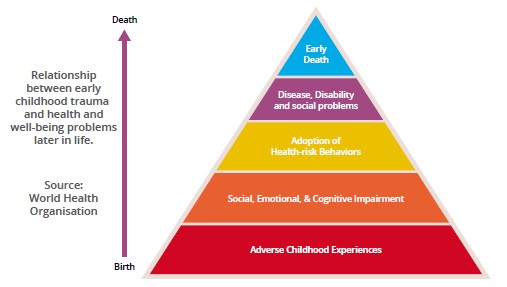

Recent research into ACES (adverse childhood experiences) by the CDC-Kaiser Permanente ACE Study in the 1990s (CDC 1997) and, more recently, by Spratt et al. (2019) suggests that there is a direct link between the impact of trauma and maltreatment on children and outcomes in their adult life. This research recognises the importance of identification and early intervention for young people affected by adverse childhood experiences in relation to outcomes in their future.

ACES can be manifested and are incrementally identifiable through the presentation of behaviours of concern. Young people in care can start to develop and demonstrate these issues in the forms of unhealthy coping strategies. This helps explain the pathways that can lead to poor health outcomes in later life. For example, if they lack emotional intelligence they are more prone to act out their emotions, resulting in risky behaviour including aggression and violence, running away, self-harm and suicidal ideation, criminality or the use of substances that block their feelings. These are behaviours that young people who are placed in special care will present with. They require high-end, intensive and holistic interventions from specific qualified and trained staff.

What is Special Care?

Residential and special care, under the care provision system in Ireland, sets out specific intervention plans and strategies that accommodate and take into account the needs of the young people placed in these services. As part of this continuum of care, special care provides the highest level of intervention to those young people in care with the highest level of needs. Special care is the provision of care to young people (12-17 years of age) in a purpose-built secure facility. Young people with severe and complex emotional and behavioural needs and deemed a potential risk to themselves and/or others, are detained under a High Court order. The placement is a short-term intervention to support their return to a community-based placement, usually residential care or, in some circumstances, foster or familial care.

Currently in Ireland there are three special care centres, which at maximum capacity can accommodate 26 young people. Most of these young people have been exposed to significant trauma and abandonment throughout their childhood and adolescent years. Over the last three years in Crannóg Nua Special Care Service young people on average are 15 or 16 years old during their placement in special care. The short-term intervention of three to nine months aims to respond to the trauma or the effects of trauma from the young people’s childhood years.

The purpose of special care as an intervention is to respond to a comparatively high threshold of need or risk. This should meet a sufficiently high threshold to justify the deprivation of the child’s liberty. The potential benefit or gain of special care can be considered in terms of outcomes. (The term ‘outcome’ will have relevance later in this chapter.) However, my experience of working with these most vulnerable, at risk and emotionally dysregulated young people is that the interventions in special care provide them with safe and caring experiences that in turn will enable them to grow to progress positively into their future. This is achieved by promoting wellbeing and teaching young people to have hope.

Special Care as an Intervention

In Ireland the programme of care for young people in special care is legislated for under the Health Care Act 2007, the National Standards (HIQA 2015) and the Special Care Regulations 2018. These documents set out the framework of expectation that young people will be provided with safe care that responds to their individual needs. Since 2018, special care centres in Ireland have been legally defined as ‘designated centres’. There is a legal requirement for them to maintain ‘registration’ that deems them fit for purpose when inspected against the Special Care Regulations. These inspections are carried out by HIQA. There is a full inspection every three years with annual inspections carried out in related to targeted or identified regulations.

The Special Care Regulations comprise 25 regulations encompassing the different areas of the provision of special care that require compliance; and five related to administrative requirements, e.g., annual fees. Each regulation includes specific indicators of compliance. Some of the regulations and evidence-based intervention strategies provided for the young people in special care are:

- positive behaviour support

- risk management

- care practice – operational policies and procedures

- staff training

- programme of care and education

- individual needs

- religion, ethnicity, culture and language.

In all circumstances, the special care centre has a responsibility to provide evidence, including in care records (another regulation), which sets out how young people’s records are maintained.

At a high level this framework of the legislation demonstrates how these elements within the care programme is designed to function as an intervention to young people during an extremely difficult period of their life. Under these high-level requirements there are three types of intervention designed and implemented locally within the individual special care centres to directly respond to the individual needs, risk and behaviours of the young people. They are: the placement plan (Welltree model of care and outcomes framework); the placement support plan; and the individual therapeutic plan. In addition, the individual education plan is designed by the school in the special care centre and is specific to the goals of education as per the curriculum provided. However, how education is supported and developed is included in the placement plan.

All these documented interventions provide guidance and direction to staff working with the young people. These plans overlap and complement each other and are co-ordinated to provide a consistency of approach. Staff working to these planned interventions provide consistency, which is key – it reassures young people and ensures that they are responded to in a positive way.

Risk Assessments

These intervention plans are also implemented and safeguarded through risk assessments. These are used daily in staff practice to ensure that staff consider areas of risk associated with elements of the young person’s care, including activities, tasks, interactions or intervention responses. The idea is that if these risks are considered and planned for, taking into account the appropriate use of protective factors, the young person will have a better chance of engaging proactively and of having a positive experience. By using the strengths-based approach and completing work regarding their risk-taking behaviour, it is hoped that they will develop the capacity to manage these risks better.

Case Study 1

One example of this is an intervention to support a young person who has a history of absconding from special care. The plan focuses on taking the young person off-site. On the first few occasions there may be safeguards in place, such as visiting different locations that are not known to the young person, introducing them to a specific activity, and ensuring that two staff are accompanying them and going on a weekday, rather than at the weekend. All these measures, it is hoped, will support the young person in having a positive experience and reducing the opportunity for them to abscond. Through review, these safeguards are reduced, and the young person can demonstrate their ability to safely manage their time off-site. These situations are all fluid and based on the circumstances related to the young person at the time.

Although all special care centres implement the intervention plans mentioned, this chapter will focus predominantly on my seventeen years’ experience and the approach adopted in Crannóg Nua Special Care Service.

Placement Plan

All young people in special care have an individualised placement plan which includes the goals set out for their time in special care. Since 2018, special care has adopted the Welltree Model of Care. This was developed by Stuart Mulholland, a childcare consultant from Scotland who has worked closely with residential and special care in Ireland to drive and support the implementation of the model. The model is also applied in the UK and internationally. It aims to guide staff in their responses to the wide range of needs and risks presented by traumatised young people who display challenging behaviours that result in harm to themselves or others. The model is underpinned by and advocates adherence to the following principles.

The model focuses on trauma and attachment-informed interventions being at the forefront of staff’s approach to their engagement with the young person and the programme of care provided. This is promoted by the therapeutic alliance created by staff with the young person. This is how staff role model and engage the young people in a healthy and safe attachment to support the therapeutic development of the young person through their sense of physical, emotional and psychological safety. This model also applies a strengths-based approach through promoting the young person’s wellbeing by providing knowledge and supporting their skill development.

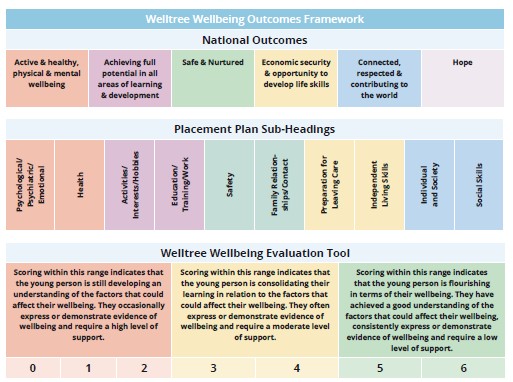

The Welltree Wellbeing Outcomes Framework

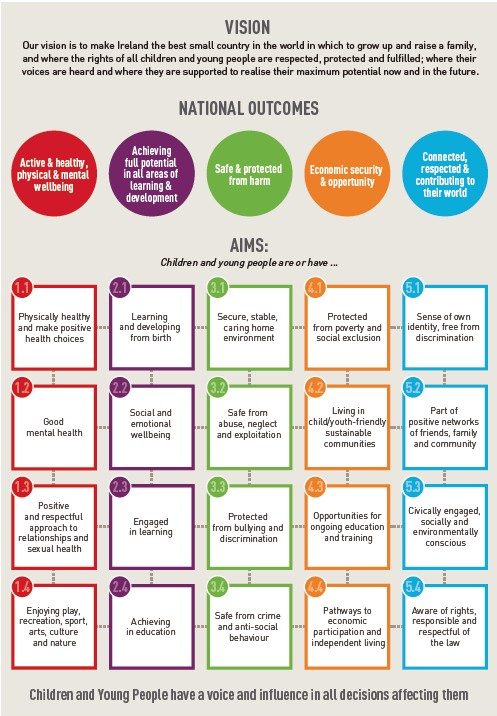

The Welltree Wellbeing Outcomes Framework was developed to support and accompany the Welltree Model of Care. The framework provides a structure for identifying goals related to wellbeing for the young person and how to measure the outcomes achieved. It is based in Ireland on Better Outcomes, Brighter Future: The National Policy Framework for Children and Young People 2014-2020. This is a comprehensive statement that sets out how we intend to achieve the best for young people under five national outcomes that include identified aims.

The Wellbeing Outcomes Framework uses the five domains from the National Outcomes and incorporates the aims within 33 indicators set out in the framework. Hope is an extra domain added to the framework because it has been proved to be of great importance in the development of wellbeing. Encouraging hope for the young person can effectively motivate them to have a positive attitude toward their future. It supports the young person to engage in setting out goals and developing their skill set in trying to achieve them. This concept is equally important for the optimism of staff in how they encourage young people in their placement in special care.

On admission, at the SCOAP (special care order application preparation) meeting, the baseline score for the young person under each outcome domain is identified. This is completed by the input of all professionals and the referral information provided. The placement plan is then designed, taking into account the priority of needs based under the domains of the outcomes framework.

In most circumstances, young people are on admission in the low developing stage in the Welltree outcomes framework. For young people to meet the criteria for special care there must be a risk to themselves or others, which is captured under the domains of ‘active & healthy, physical & mental wellbeing’ and/or ‘safe & nurtured’. Therefore, during their placement in special care, it is these domains that we want to see an increase in, as this demonstrates that the young person is ready to move on from the security/detention of the special care service. The aim is that the young person’s score has increased and in the ‘consolidating stage’, creating the opportunity for this progress and motivation to be continued in their placement in the community. This is achieved by engaging the young person in their placement plan goals and reviewing the outcomes of the plan.

How we engage the young person

Implementing the model has encouraged the centre to consider and plan for how we provide the principles set out in the model and framework. Staff have all received training so that we have a shared understanding of the language and goals and aims of the intervention; and so that we are educated on the effects of trauma and attachment. From admission, there is a shared understanding of the risks that have resulted in the young person being placed in special care, the requirement of the trauma- and attachment-informed interventions, and a clear plan for improving the young person’s wellbeing. Staff are supported to understand how their relationships and interactions with the young person provide a therapeutic alliance. This is achieved by recognising why we intervene with the young person.

Young people with past experiences of trauma and attachment can be mistrustful in their interactions with staff and will act out their feelings. Therefore, staff need to provide consistent and safe responses that allow young people to feel cared for. Utilising risk management strategies alongside a strengths- based approach facilitates staff to provide multiple opportunities in the life space for young people to exercise choice, develop skills and achieve their potential. This is balanced against how the young person’s wellbeing can be promoted in a careful assessment by staff. This helps to ensure that considerations of risk are weighed against the effects this may have on the short-, medium- and longer-term wellbeing of the young person. This is communicated to the young person to ensure that they develop the capacity to manage risk and promote their own wellbeing when they leave the special care environment. Carrying out this complex and extremely sensitive work demonstrates the skilled role social care staff have in using a relational and strengths-based approach to respond to the young people’s high levels of risk and wellbeing needs.

From admission, the young people are encouraged to be actively involved in their programme of care. The model also recognises the participation of key stakeholders in the young people’s life, including family, social workers and other professionals, and how the integration of interventions will provide positive outcomes and support to the young person in their participation. The placement plan incorporates a holistic action plan to support the goals set out. There is careful consideration given to how young people are encouraged to achieve their placement goals. This could be through daily routine, creative ways for key-working or individual work, and behaviour management plans. The key workers meet with the young person monthly and identify with them the areas that they are going to focus on for the coming month. The key workers then also build structured individual work sessions into the young person’s weekly plan for them to complete.

How do we evaluate and review?

At the end of each month, related to the placement plan, the keyworkers review the evidence of work completed by the young person in relation to the indicators set out. This is not solely restricted to the individual work, but all evidence of how the young person has managed in that aspect of care. For example, the goal may be related to the indicator ‘learning & development’ – The young person understands the importance of education or training and demonstrates this through positive behaviour and attitude. The evidence may be that the young person has engaged in structured individual work regarding the importance of attending school and demonstrates this understanding by having improved attendance at school as part of the programme. The following table is an example of the evidence for a score of 2, ‘under-achieving full potential in all areas of learning & development’.

|

Achieving full potential in all areas of learning & development SCORE 2 |

||

|

Reason for indicators chosen: Mary’s educational attendance has historically been inconsistent and can often require support within Crannóg Nua Mary appears to manage her behaviour better when she is kept active and channels her energy in a positive way. |

||

|

2(a)The young person understands the importance of education or training and demonstrates this through their positive attitudes and behaviour |

||

|

Action needed |

Identified person required |

Status |

|

The staff team will continue to follow Mary’s placement support plan, in relation to supporting her attendance in Crannóg Nua special care school. Complete individual work (1) on the importance of education and future education goals. |

Staff team |

Action in progress |

|

2(b)The young person understands the importance of hobbies/activities and demonstrates this through their positive attitudes and behaviour |

||

|

Action needed |

Identified person required |

Status |

|

Mary’s assigned staff will continue to complete a daily plan with her. This will include identified pro-social activities, both on and off site – in keeping with her placement support plan. Complete individual work (1) on interests/hobbies and the benefit of participating in these within the community. This individual work is to be related to transition visits with onward placement and the importance of positive engagement in these, prior to transitioning back to their centre. |

Staff Team |

Action in progress |

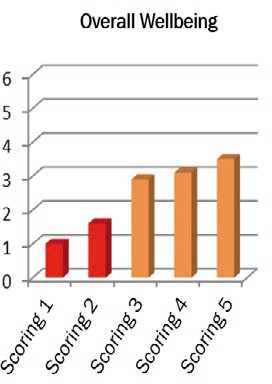

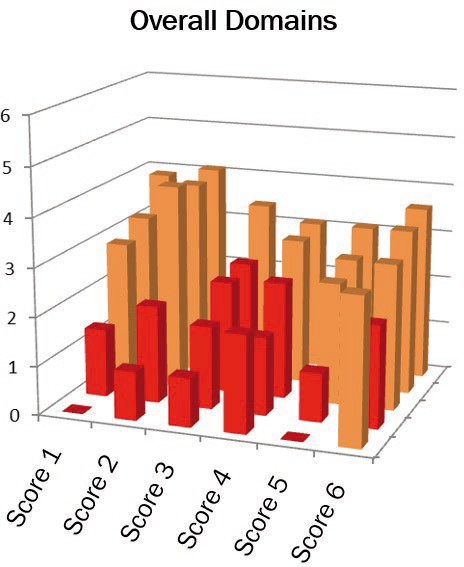

The scoring is completed and reviewed by the multi-disciplinary team, based on the evidence provided. The framework adopts a strengths-based approach and it can be difficult to apply in practice, but we encourage the professional team not to draw on the negative behaviours. However, the framework does also avoid this by looking at how much of the time the young person has been successful in demonstrating the behaviour. The framework has also supported changing the perspective from how many significant events has the young person has: the approach now supports and recognises how the young person has engaged positively outside these periods and also how they have managed or responded when a significant event has occurred. The graphs demonstrate how the interventions implemented within special care are successful in improving these young people’s wellbeing. There is a conscious effort to set out achievable goals to encourage the young people’s participation and motivation to engage them and for them to be proactive in their overall placement plan. The scores of the outcomes are then included in graphs, which provide a visual aid in representing the improvements in the young person’s wellbeing. If the young person is having difficulty, the scoring allows for a re-focus of the goals required and also for the multi-disciplinary team to review the cause of the deterioration.

Staff actively encourage young people to participate in their scoring to develop an understanding of what supports them in their progression towards their placement goals. What has also been highly beneficial is where the placement that the young person has come from, or is going to, uses the Welltree Model of Care. Previously, when the scoring was completed on admission of a young person, the score was in line with the scores of the residential placement. This also means that the goals can be set out and adapted to promote joint working between the services and support the transition for the young person back to their placement. The scores also provide feedback to the special care centre regarding the overall progress in each of the domains. It allows for analysis of how the special care unit is doing with regard to improving the overall wellbeing of the young people and also the individual domains. This is something which has not been available in the past in relation to providing data on the outcomes from the interventions provided in special care.

TASK 1

What does wellbeing mean to you? How have you promoted your own wellbeing? How has it been promoted by individuals in a social care setting

where you have worked? What intervention plans support this?

Individual Therapeutic Plan

On admission to special care the therapeutic rationale of the placement is considered and agreed by the multi-disciplinary team. This takes into account the therapeutic needs of the young person based on their presenting risks and previous trauma. Each special care unit has an in-reach ACTS (Assessment Consultation Therapy Service) team. These are made up of multi-disciplinary clinicians including psychology, speech and language, social work and substance misuse. On admission, the identified ACTS clinicians will complete the AIM 40 from the Ambit Model which assists them in identifying the priority of therapeutic needs.

‘Aim 40’ is used to plan and sequence the intervention for the period of special care, to assist the team in gathering information from all the multi-disciplinary team involved and the young person to ascertain what they believe to be the key problems. It involves 40 questions which look at areas from daily living skills to clinical need. Typically, these young people/families are enmeshed in multiple services with multiple professionals involved and can be working towards different individual goals. The objective of ‘aim 40’ is to create alignment among the network of clinicians about the key problems and to focus the intervention with the young person on working towards agreed goals. This information informs the development of the individual therapeutic plan (ITP) for the young person. It will take into account any diagnosis, learning or mental health needs and effects of trauma that needs to be addressed. The ACTS team will work with the young person, their family, the staff team in special care and their identified onward placement as part of the AMBIT model that they implement. The ACTS psychologist or clinical team manager may also liaise with the community-based psychiatrist if the young person has significant mental health needs or is prescribed medication related to mental health. The ACTS team engages the young people with, for example, self-regulation, responding to self-harm and suicidal ideation, family work, speech and language/processing needs, responding to diagnoses such as ADHD/ADD/ASD and life story work. The ACTS team may also complete assessments based on the needs of or concerns for the young person.

How we engage the young person

As with all intervention plans multi-disciplinary engagement is critical if we are to achieve positive outcomes for the young person. This is ensured by having multi-disciplinary participation in all meetings pertaining to the young person’s programme of care. Although ACTS retain ownership of the ITP, the other professional groups, including the staff team in the centre, can support how the young person is engaged to achieve the goals set out for them. For many reasons young people can struggle to engage with this therapeutic plan. This can be due to fear, stigma, not thinking there is something wrong with them, the formality of therapy and maintaining self-control. However, there are ways that this process can be assisted and supported for positive outcomes.

On admission to special care, it is crucial that there is a there is a culture promoting the benefits of the young person engaging in their therapeutic plan. Although young people should never be forced into therapy, it should have a similar weight of importance as education. When staff actively promote their therapeutic plan, it can be influential for the young person. This is certainly enhanced when the staff team have a positive and proactive working relationship with the ACTS team.

Young people in special care will generally have high levels of anxiety as a result of their adverse childhood experiences and in dealing with the whole process of the admission to special care. As part of this, young people are educated and informed regarding the role of ACTS through individual work and information captured in the young person’s (information booklet) statement of purpose. Where a one-to-one session for the young person and their ACTS clinician is required, staff incorporate this into the young person’s weekly plan so that they are aware when it is happening. The time of the day, where the meeting will happen and a fun activity after the session, are all considered to support the session. On occasion, if appropriate and requested by the young person, staff can remain with them as support. Staff can really demonstrate skill in supporting the most reluctant young people to attend these sessions – again, relationships and trust are key.

To further support the engagement of the young person in their ITP there are regular interactions between ACTS and the staff team. This can also help in circumstances where the young person won’t engage directly with the ACTS clinicians. Staff may complete information required for assessments or complete planned individual work that supports the therapeutic goals, for example the ‘Reduce the Use’ programme for substance misuse, or self-regulation techniques for self-harm.

How do we evaluate and review?

The ITP is reviewed by ACTS every month. A representative attends the young person’s child in care review or multi-disciplinary team meeting to provide feedback and support the update of the care plan. There is also an ACTS meeting every fortnight with staff and management to review the aims and progress of the ITP. Where difficulties have arisen, possibly relating to the young person’s engagement or an escalation of behaviour, alternative strategies can be considered. There are also regular focused meetings between ACTS clinicians, the unit case manager and key workers. The ACTS team also attend staff meetings to provide information on how to support the young person. This is another example of the joint approach in responding to therapeutic needs.

Finally, ACTS complete workshops relating to the individual young people at intervals throughout their placement. They provide therapeutic support and understanding to the staff in relation to the young person’s trauma/attachment and presentation of behaviours. They review the frequency of behaviours and also how to address and support risk management strategies on discharge. When the young person has an identified onward placement, the emphasis and priority is on a collaborative approach. Where appropriate the ACTS team support the young person and the team in the onward placement to support them managing successfully in the community.

1 Individual Work. This is direct work completed by staff with the young person. It is goal- oriented and documented and recorded as part of the programme of care. It can be planned as part of placement plan goals or can be opportunity led.

2 Emotional Intelligence. ‘If you are tuned out of your own emotions, you will be poor at reading themin other people’ (Goleman 2011).

Placement Support Plan

The placement support plan (PSP) is the document that sets out the behaviour management interventions for the young person in the context of therapeutic security. This is necessary because young people placed in special care demonstrate a range of extremely challenging behaviours that cannot be safely managed in the community. They might include substance misuse, exploitation, absconding behaviours, violence and aggression, self-harm, allegations of abuse and seeking medical treatment. There is a significant complexity in the behaviours presented by young people in special care and the needs that these behaviours meet. This is particularly challenging for staff when young people are placed together in special care units.

At an organisational level there are provisions relating to the application of therapeutic security principles in special care that support the daily implementation of positive behaviour support and behaviour management. The centres incorporate a number of safety features, including, among others, secure doors and windows, locked internal doors, CCTV, personal alarms for staff, and identified safe rooms. The centre is designed to be able to respond to significant high- end behaviour to support both staff and young people to be safe. As a balance to this focus on safety, the environment is decorated to provide a homely and warm feeling so that young people feel welcomed and comfortable. The young people are encouraged to participate in creating the décor of the centre, including how they decorate their own rooms.

In relation to staffing, there is a least a 1:1 staff to young person ratio, staff working night shifts, and all staff are trained in TCI (therapeutic crisis intervention). A significant part of this training is that staff are trained to physically restrain the young person if considered necessary to protect the young person from harming themselves. De-escalation techniques are the principal method employed by staff to assist the young person to regulate their behaviours. These are reviewed regularly by both internal and external professionals to ensure that practice is adhered to and developed in a manner that safeguards the young person’s wellbeing. The optimum outcome of this training is that staff are confident to respond to challenging behaviour and the young people feel safe and secure. It also supports an understanding of the indicators of escalation in challenging behaviour to ensure that interventions are put in place earlier and with low-level responses that enhance the young person’s own self-regulation. The PSP outlines how the young person can respond and react in times of difficulty. The intervention plan identifies the challenging behaviour that the young person may engage in, signs of triggering and/or escalation and the incremental stages of responses and de-escalation methods that can be implemented within the special care environment.

How we engage the young person

On admission, significant individual work is carried out with the young person. This includes their understanding of the rationale for their placement in special care, the expectations and routines of the centre and how they will be supported to manage their challenging behaviour. Staff work exceptionally hard and can develop relationships in a really quick time period. These relationships underpin how staff can support the young people to feel safe and secure and in turn promote appropriate coping mechanisms. Staff utilise all opportunities outside crisis cycles to proactively engage the young people in their wellbeing. This includes promoting good sleepbygiene and routine, attending school, eating a healthy diet, keeping physically active and having fun, all of which can reduce incidents and support the development of appropriate coping mechanisms.

Young people are made aware that they have a PSP. The aim of this intervention plan is to provide direction in how to respond to and manage challenging behaviour displayed by the young person. Where appropriate, the young person is supported to engage in developing or updating their PSP. The plans are all unique to each individual’s needs, risks and cognitive ability. Many young people in special care have speech and language and/or language processing needs. This can mean that when they are emotionally heightened they are less likely to be able to communicate effectively or respond to verbal prompts or commands from staff.

As part of their placement plan, the at-risk behaviours that led to the young person being admitted to special care is a strong feature of the structured key working or individual work carried out by staff with the young person. This is an opportunity to discuss these issues in a planned and safe way when the young person is at baseline. It can also support engaging the young person around de-escalation techniques and self-regulation skills. An example of this is where occupational therapy guidance has been provided regarding their sensory issues. It can also include encouraging the young person to use sensory tools such as fidgets or soft balls to self-regulate instead of possibly resorting to self-harm.

One of the most significant parts of how we engage the young person in their intervention plan is conducting an LSI (life space interview) after an incident. This is part of the TCI model. It is a structured discussion with the young person after a significant event. It explores what happened, tries to identify the trigger, links the feelings to the behaviour and tries to consider alternative behaviour management strategies for the future. This empathic and relational approach allows the young person to address and reflect on their perspective of the incident and be supported by staff to explore alternative coping mechanisms for the future. It may also provide staff with learning or information, including possible triggers and/or responses that can be updated in the PSP.

How do we evaluate and review?

The evolution and development of special care has led to greater sophistication in how we review behaviour management and promote positive behaviour support. In my experience this is an area that has developed significantly and has benefited from reviewing systems that ensure best practice and positive outcomes. It is imperative that risk assessments, positive behaviour support and behaviour management remain live and are updated and reviewed as required. Staff in their practice are trained and guided in their responses to challenging behaviour. They are also prompted to take learning from each significant event and amend or update the PSP as required.

There are robust incremental reviewing systems within the service which feed into the PSP for the young person to support their individual needs. When an incident has occurred, the staff completing the significant event report will consider and include any learning or possible updates required for the PSP based on the event. This will also include anything pertinent raised by the young person in the LSI. The staff may also complete a shift review to discuss how the shift/incident was managed and this can also provide feedback or follow-up. The deputy social care manager will then review the significant event document and a ‘manager review & response’ form will be completed by the social care manager. This ensures that the PSP was followed in line with policies and procedures.

On some occasions there may be a response meeting following a significant event. This consists of the management team, social care leaders and some staff. The meeting reviews what has occurred and what is the response plan. Following the meeting, changes to the PSP may be required. A debrief meeting may be provided for the staff involved in the incident. This is usually facilitated by the person in charge or a manager to provide emotional support to the staff member by letting them discuss the incident in a structured and protected forum. It allows staff to gain clarity or discuss the actions or decisions made during the incident. It is also generally very productive in providing further learning and reflective practice.

In addition, there are higher-level reviews. A monthly centre SERG (significant event review group) is attended by a Tusla National Training Lead, a Welltree consultant and a health & safety representative. The centre’s management team, including the director and PIC (person in charge), staff and ACTS attend. The previous month’s significant events are reviewed based on level of restrictive practice used, a pattern or theme emerging, or on consideration of challenges or concerns in relation to the significant event. The group then review the incident or patterns of incidents. Not only is learning achieved, but there is also a recognition of the good practice that has been achieved. This forum is extremely effective and has been pivotal in supporting and responding to the challenges of significant events and high-risk behaviour in the centre. At national level, a SENRG (Significant Event National Review Group) is made up of representatives of senior management from each special care centre. High-end themes are reviewed and addressed at this meeting.

In the centre, in addition to the focused review of significant events, trend analysis is completed. This looks at the statistics related to the data on incidents and behaviours presented. Each month, quarter and year there is a review to provide information on the rationale or antecedents to behaviour and to identify where high-end service-level responses or strategies are required. All of these reviewing mechanisms and reflective practice support the development and implementation of the intervention plan to promote positive outcomes. In special care, this top- level governance is required to ensure that the most appropriate and safest response is applied to the behaviour that occurs. Constant reflection and learning supports the young person’s participation in the intervention plan. This is achieved through the consistent and competent actions of the staff in the form of trauma-/attachment-informed responses that promote wellbeing.

Task 2

Using the ICMP (Individual Crisis Management Plan) template from TCI (Therapeutic Crisis Intervention), develop an intervention strategy for

a service user in your placement.

Special care is one of the highest-end interventions that can be provided to a young person in the care system in Ireland. As outlined above, there are influential factors involved in how individual interventions are implemented and how young people are supported to have positive outcomes. The plans should all complement and work cohesively together to support the overall care plan of the young person so that they successfully step down from special care. In addition to the evidence and information provided, in my experience there are other elements that can be provided within the service to enhance the successful delivery of individual interventions.

In the first instance, the centre needs to be creative in how it reviews and maintains motivation in implementing the plans. Part of this is recognising how to engage the young people in the environment. In Crannóg Nua there is always consideration given to the environment, taking into account both the requirements of the intervention of special care, including safety and security, and also the need for the environment to be comfortable and inviting for the young people. This ensures that the centre is both safe and able to support responses to challenging behaviour and also a space that is pleasant and homely for young people so that they engage positively in the therapeutic programme.

After the centre re-opened as a special care service in 2017 it was evident that the building’s acoustics were not supporting a trauma-informed approach. There were concerns regarding how the noise travelled and the effect of this on the young people, with doors banging, people shouting or talking and general echoes. Sound boards were installed, and the impact was immediate. There is now a pro-active approach to review how the environment can be developed to respond to the sensory needs of the young people to support their engagement in the intervention plans. Examples are using colour, creating texture and managing light with curtains, having different surfaces to sit on (sturdy couches, beanbags), taking account of the purpose of rooms, having blackboards to write on instead of graffiti and use of diffusers or air fresheners to scent the rooms. There is significant consideration given to making the young person’s bedroom feel safe, comfortable and individual to their taste. These developments demonstrate to the young people that their needs and wishes are taken into account, which really helps to develop the relationship and therapeutic alliance.

The fulcrum of the service is the staff team. Interventions will only be as successful as the team that is working with them. The team need to be supported to become confident in implementing intervention plans. They need recognition and understanding to process the challenges in the special care environment. There should be a culture and drive to ‘do better’ and use reflective practice in all aspects of the care provided. This also includes staff accountability and places an emphasis on professional development. The leadership and culture of the centre will guide how this is received and achieved by the staff team.

The implementation of these interventions in special care supports the young person to progress within their programme of care. In the short term the outcomes for the young person can be measured, depending on how they progressed within special care and the placement that they stepped down to. However, there is currently no data or research on the outcomes for young people post-discharge from special care. Other than the contact that staff may maintain with the young people or information provided to staff or professionals, the young person’s outcomes are unknown. This research and data would be very beneficial to support the ongoing development of the programme of care based on outcomes or feedback from the young people. In the absence of that, the best outcome or measure comes in providing the young people with what they feel is a positive period and opportunity of their life that they were kept safe and care for. And that there was hope.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

Special care is a unique environment that can provide a student on placement with a wealth of knowledge and experience. To support this, they need to be active and engaged in their approach and armed with the relevant information on the service prior to the placement

Beginning of placement: Ask the student to review a programme of care for a young person they are working with in the placement. While upholding confidentiality and data protection, ask them to identify the intervention goals set out in the intervention plans.

Middle of placement: This is the time for the student to immerse themselves in the progression of the intervention plans and understand how they are implemented, evaluated and reviewed. This will be supported by:

- Meeting with the identified key team and case manager and agree some individual work in line with Welltree outcomes framework goals that the student can complete with the young person in the company of a staff member.

- Attend key training provided in the centre, if available. This may include behaviour management, including TCI, and Welltree.

- Using the outcomes framework, complete a scoring for a young person with a key worker and young person, if appropriate.

- Attend a staff meeting, ACTS meeting and SERG to see how intervention plans are evaluated and reviewed.

- Attend a child in care review if appropriate. This will give the experience of multi-disciplinary working and how the full programme of care is reviewed to update the care plan.

End of Placement: Ask the student to identify any other evidence of practice by the staff, the programme or environmentally that supports the young people’s responses to the interventions.

References

Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families (2020) Online AMBIT Manual. Available at <https://manuals.annafreud.org/ambit/index.html> [accessed 24 June 2021].

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (1997) CDC-Kaiser Permanente ACE Study. Available at <https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html> [accessed 24 June 2021].

Goleman, D. (2011) ‘Emotional intelligence’, interview with Daniel Goleman on Leadership and the Power of Emotional Intelligence, Forbes, 15 September. Available at <https://www.forbes. com/sites/danschawbel/2011/09/15/daniel-goleman-on-leadership-and-the-power-of-emotional- intelligence/?sh=7b3de5d76d2f> [accessed 24 June 2021].

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2015) National Standards for Special Care Units. Available from <https://www.hiqa.ie/reports-and-publications/standard/national-standards-special- care-units> [accessed 24 June 2021].

Office of the Attorney General (2017), S.I. No. 634/2017 – Health Act 2007 (Care and Welfare of Children in Special Care Units) Regulations 2017. Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2017/ si/634/made/en/print> [accessed 24 June 2021].

Spratt, T., Devaney, J. and Frederick, J. (2019), ‘Adverse childhood experiences: Beyond signs of safety; reimagining the organisation and practice of social work with children and families’, British Journal of Social Work 49(8). Available at <https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/article/49/8/2042/5372389>.

Welltree (2020) Developing the Welltree Model of Care. Available at <https://socialcareireland.ie/wp- content/uploads/2020/11/Presentation-Social-Care-Ireland-2020-Copy.pdf> [accessed 24 June 2021].