Chapter 58 – Delores Crerar (D4SOP3)

Domain 4 Standard of Proficiency 3

Be able to evaluate and reflect critically on own professional practice to identify learning and development needs; be able to select appropriate learning activities to achieve professional development goals and be able to integrate new knowledge and skills into professional practice.

|

KEY TERMS Core values and belief systems Impact of your past Use of self Trauma-informed Learning activities

|

Social care is … a working relationship with self and others which is based on the right to respect, dignity, empowerment, choice and self-determination. |

Underpinning this proficiency is an understanding that in order to reflect critically on our professional practice we need to understand the role of values, attitudes and beliefs. The importance of critically reflecting on our practice is a consistent theme in the social care literature; however, from my experience as a family support manager how we do this warrants more attention. This chapter adopts a three-pronged approach to critical reflection: values, attitudes and beliefs.

|

Values |

A value is a measure of worth that a person attaches to something; values are reflected in the way we live our lives, e.g.,‘I value my job.’ |

|

Beliefs |

Ideas that are accepted to be true, even though they may be unproven or irrational, e.g.,‘I believe in life after death.’ |

|

Attitude |

The way a person applies or expresses their values and beliefs through words and/or behaviour, e.g.,‘I hate college.’ |

|

Use of Self |

The merging of a practitioner’s professional training, knowledge and techniques with their personal self, which includes personality, belief systems, life experiences and self-awareness, to support a client in a therapeutic relationship. |

Core Values and Belief Systems in Professional Practice

Core values can relate to a personal, business or professional setting. The importance of reflecting on our own practice starts with an awareness of factors that shape our practice. Values are inherent to a person and can help them to distinguish right from wrong. When a person or business cannot identify their core values, it can become very difficult to plan for or achieve a clear vision of the life or business that is wanted. When a person is clear on their values and beliefs, they can assess their actions and behaviour accurately. Some core values have been transmitted to us through the family or the community in which we live or grew up. Core values should not be viewed as a fixed asset or definitive list; they are malleable. Some core values may strengthen over time, while others are adjusted due to personal growth and development, the impact of life experiences, or the personal processing of societal pressures or influences. We make a conscious decision to adjust or change our values when they are no longer in alignment with who we believe ourselves to be or our future vision of the type of person we want to become. Below are some reasons why it is important for social care workers to be aware of the core values they hold:

- Define the essence of your character (who are you when no one is looking).

- Reflect the situations and topics you stand for and care about as a person.

- Communicate to others your philosophy of life.

- Guide your behaviour and influence the decisions you make in life.

- Guide your behaviour and influence your actions when working professionally with others.

TASK 1

Make a list of your most prominent personality traits. Identify how these traits can act as strengths and limitations when relating to those you supportin professional relationships.

Studies have demonstrated that while a theoretical knowledge base and mastery of skills are fundamental to social care work practice, better outcomes with people are achieved when a social care worker demonstrates authenticity and can harness their personality traits as a therapeutic tool when working with others (Edwards & Bess 1998; Baldwin 2000). To do this effectively we as practitioners must take time for self-discovery, so that we are presenting our ‘authentic self’ at all times.

TASK 2

Reflect on the following points and discuss how this information is relevant to your professional practice.

What are my strengths and limitations regarding skills, knowledge and aptitude for professional practice within the social care sector?

What people and goals in my life are most important to me?

What aspects of myself am I unwilling to compromise in relationships or employment?

What are the factors that motivate me or drive me into action?

What does success look like to me?

Additionally, belief systems do not necessarily relate to our religious or spiritual orientation, rather they help us to organise and make sense of the world. It is important as social care workers to ensure that we are not imposing our own values or belief systems on those we work with; by doing so we fail to honour the individual’s personal life journey and right to self-determination. We must be cognisant of developing strong foundations in all our helping relationships by demonstrating empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard (Rogers 1957). Each person is unique, and each person has developed a unique worldview.

Impact of Your Past on Professional Practice

This section explores the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and life experience on personal and professional identity formation and your practice. Since 1995, the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study has assembled evidence of the effects of ACEs on people’s life outcomes. In the original study, two-thirds of more than 17,000 subjects who filled out confidential surveys about their childhood reported having experienced at least one ACE (ten being the highest number of ACEs the test accommodates). The ACE test is divided into three groups: abuse, neglect, and household challenge. People with higher ACE scores are at increased risk of experiencing anxiety, panic or depressive disorders, of becoming an alcohol or substance user, of engaging in promiscuous sexual behaviours, and of developing obesity, heart disease and cancer. ACEs in the general population are common and many individuals have experienced at least one ACE in childhood. Some population groups in society are more vulnerable to experiencing ACEs because of the economic and social conditions in which they live.

Anda et al. (2004) identified that employers and medical practitioners have difficulty managing relationship issues, absenteeism, emotional distress, substance abuse and somatic symptoms in employees who are not addressing the impact of their own ACEs on work performance. We cannot thrive as individuals or practitioners while we are still learning to survive the impact of our past life experiences and trauma. We need to acknowledge how common trauma is and to understand that practitioners and clients alike will have their own unique relationship with trauma. Becoming personally and professionally aware of trauma-informed practice requires us to make a paradigm shift from asking, ‘What is wrong with the person?’ to ‘What has happened to this person?’ (Harris & Fallot 2001) or indeed from ‘What is wrong with me?’ to ‘What has happened to me?’ As professionals we can commit to undertake training in trauma-informed care so that we become more aware of approaches to supporting ourselves and our clients in ways that enable us to feel safe, seen, heard and respected.

The nature of the social care system can often create a fast-paced and action-based practice whereby ‘doing’ is often a more predominant model than ‘thinking’ within the daily interactions with others. As social care practitioners we are required to work in a reflexive manner, and this does mean taking the time to stop and explore the conscious and unconscious factors influencing our ‘doing’ with others. Reflexivity enables us to identify what aspects of our life experiences are resonating with the stories of those we support and what aspects are triggering uncomfortable feelings or unprofessional responses in our working relationships. This reflection is core to understanding the gaps in our knowledge, the areas of professional practice we need to improve, to identify learning and development needs.

The nature of the social care system can often create a fast-paced and action-based practice whereby ‘doing’ is often a more predominant model than ‘thinking’ within the daily interactions with others. As social care practitioners we are required to work in a reflexive manner, and this does mean taking the time to stop and explore the conscious and unconscious factors influencing our ‘doing’ with others. Reflexivity enables us to identify what aspects of our life experiences are resonating with the stories of those we support and what aspects are triggering uncomfortable feelings or unprofessional responses in our working relationships. This reflection is core to understanding the gaps in our knowledge, the areas of professional practice we need to improve, to identify learning and development needs.

Learning Activities

This section provides examples of learning activities and tools to help you identify and achieve your professional development goals and integrate this new knowledge and skills into your professional practice.

1. Frozen, Unfreezing and Flourishing Practitioners

Frozen practitioners are those whose values and belief systems are rigid and uncompromising; they view the world with a fixed mindset. They may be new to the field of social care or may have become rigid in their practice due to resistance to change, poor management, lack of supervision or compassion fatigue. Through the supervision process they may be encouraged or challenged to unfreeze their thinking and explore the interplay between their personal and professional values and belief systems.

An unfreezing practitioner has begun to develop a greater awareness of their personal attitudes and motivating factors which act as the foundational structures to their values and belief systems. With new-found knowledge and insights, the practitioner develops new skills from which personal and professional behaviour changes can be seen. Over time and with commitment the practitioner can easily recognise how their values and belief systems can be utilised for the benefit of self and others within the field of social care.

A flourishing practitioner will be proactive in utilising supervision as a tool for self-discovery and deepening professional practice. This practitioner is acutely aware of their own values and beliefs but also ensures that they do not allow their personal biases or prejudices to impact on the working relationship with others. They adhere to strong ethical boundaries and self-care practices to nurture their relationship with self and others.

|

Characteristics of the Frozen, Unfreezing and Flourishing Practitioner |

||

|

Frozen |

Unfreezing |

Flourishing |

|

Unaware of their personal bias and prejudice. |

Is becoming aware of their personal bias and prejudice. |

Ensures own biases and prejudices do not enter the working relationship with others. |

|

Unaware of their values and beliefs. |

Can identify some of their values and beliefs. |

Can clearly identify own values and beliefs. |

|

Cannot accurately assess own strengths and weaknesses. |

Becoming aware of own strengths and weaknesses. |

Clearly identifies own strengths and weaknesses. |

|

Is resistant to feedback, constructive criticism or mentoring relationships. |

Is open to feedback, constructive criticism, or mentoring relationships. |

Sees feedback, constructive criticism or mentoring relationships as mechanisms for improving own practice. |

|

Does not value the supervision process as a tool for ongoing professional development and discovery. |

Is engaged in and appreciates supervision as a tool for ongoing professional development and discovery. |

Supervision is viewed as a tool for deepening ongoing learning, development and discovery as a practitioner. |

|

Responds to working with vulnerable population groups in a ‘one size fits all’ approach. |

Is becoming flexible in their response to working with vulnerable population groups. |

Experienced in design and delivery of evidence-based approaches to working with vulnerable population groups. |

|

Refuses to utilise or disengages from opportunities for ongoing professional development. |

Participates in opportunities for ongoing professional development. |

Opportunities for ongoing professional development are viewed as mechanisms for improving own practice. |

|

Does not engage in reflective practice. |

Is becoming familiar with reflective practice as a means for learning and development. |

Reflective practice is used to identify how the worker experiences themself in the work they do with others. |

|

Cannot identify when poor boundaries are present with staff, clients and stakeholders. |

On reflection or with guidance can identify when poor boundaries are present with staff, clients and stakeholders. |

Adheres to strong ethical boundaries when working with staff, clients and stakeholders without support and guidance. |

|

Cannot identify when they are displaying characteristics of compassion fatigue or burnout. |

Understands the key characteristics of compassion fatigue and burnout and monitors self accordingly. |

Adheres to strong self-care practices to combat the onset of compassion fatigue or burnout. |

2. The Supervision Process as a Tool

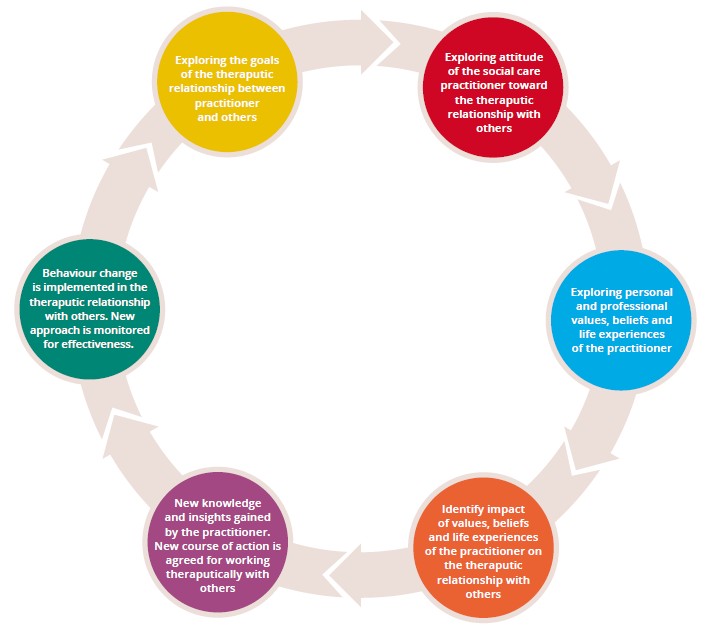

Effective social care workers know when to seek help with processing personal and professional concerns, stressors and experiences. The supervision process is an invaluable tool for social care workers through which self-discovery and professional development can take place. Within this space the practitioner is constructively challenged and supported to integrate new knowledge and skills into professional practices. Other chapters have focused on the role, purpose and functions of the supervision process (see Chapters 60 and 79). The focus here will be on how the practitioner can become more responsive and take responsibility for their own ongoing growth, development and needs within the context of the supervision process. Working in partnership with the supervisor, the practitioner looks at the therapeutic relationships they are engaged in, and they explore how their personality, values and belief systems are resonating with, supporting or impeding another’s growth.

By focusing on the reflexive cycle, the practitioner is provided with space to identify key learning and to integrate this new-found knowledge with tangible working practices that will be mutually beneficial for the practitioner and client within the therapeutic relationship.

Reflexive cycle of supervision to identify how personal values and beliefs are impacting on the therapeutic relationship with clients (Crerar 2021).

Case Study 1

The Reflexive Model of Supervision

Emer is a third-year student attending her placement in a local family resource centre. Emer has been asked to shadow the family support worker, who is currently working with a women’s group whose members are predominantly single parents, with low educational attainment and who are long-term unemployed. The family support worker has noticed that Emer seems to have a low frustration tolerance with the group participants’ viewpoints when topics such as barriers to education and employment are discussed in the group. Emer has been noted as telling the ladies that ‘there is plenty of opportunity to return to education’ and ‘plenty of jobs out there’. This has led to some group members feeling ‘demoralised’ and ‘ashamed’ of their life circumstances. One member of the group has refused to return to the next session unless Emer apologises for her comments. Emer does not see an issue with the comments she has made. Emer has been asked to use the reflexive model of supervision to identify how her personal values and beliefs have impacted on her therapeutic relationship with this member of the group.

Phase 1. The goal of the therapeutic relationship between Emer and the women’s group was to provide Emer with practical experiences of understanding and supporting vulnerable client groups while attending field placement. The background history of the group, the group’s socio-economic circumstance and the individual life circumstances of each member were discussed with Emer so that she could connect with the experiences of each individual.

Phase 2. Emer has identified that she finds the group conversations frustrating. She believes that each of these women had a choice to have children and have a choice to return to employment or education. She feels some are unwilling to change their life circumstances.

Phase 3. Emer has identified that she comes from a home where two parents are present and there is no history of unemployment. Her parents have instilled in her the values of hard work and study. Her parents are supporting her financially to attend college.

Phase 4. Emer recognises that her own family and life situation is not the same as those attending the women’s group. Emer identifies that she has been supported during early childhood and adolescence to complete her education and continue her studies at college. Emer identifies that she has had role models to demonstrate the benefits of engaging in education and employment. She identifies that she has grown up in a home free from the effects of poverty.

Phase 5. The supervisor and Emer discuss the reasons for early school leaving and long-term unemployment which are actively presenting within the group. Emer develops a greater awareness of the complexity of the barriers which are preventing group members availing of education and employment opportunities. She acknowledges her previous opinions and beliefs relating to the group’s dynamic were limited and biased. Emer agrees to sit with and listen to each group member’s personal story at their next meeting.

Phase 6. Emer returns to the group and apologises for her low frustration tolerance with the group. Emer begins to actively listen to each person’s story and connect with the impact of each person’s lived experiences. She becomes more compassionate towards the group members’ situations. The group members note feeling ‘less judged’ by Emer.

3. Use of Self in Social Care

The term ‘use of self’ can sometimes be confusing for a novice practitioner to understand and to embody. The ‘use of self’ relates to the combination of values, skills and knowledge gained

through study, in conjunction with one’s personality traits, belief systems, cultural heritage and life experiences (Dewane 2006; Lyons 2013). Understanding self is central to critical reflection on your professional practice. Schneider-Corey and Corey (2002) note that it is essential for those working in the therapeutic professions to be aware of one’s own identity, feelings, limitations, strengths and frustrations so that they can relate to and support their client better. They assert:

‘A central characteristic for any therapeutic person is an awareness of self – including one’s identity, cultural perspective, goals, motivations, needs, limitations, strengths, values, feelings, and problems. If you have a limited understanding of who you are, you will surely not be able to facilitate this kind of awareness in clients.’ (2002: 32).

Kaushik (2017) argues that knowing self is a precondition to knowing others. How do we learn to use self in the field of social care? There must be a willingness to construct and deconstruct our concept of who we are, our values and our beliefs as we grow and mature within our personal and professional identities. This journey of self-awareness requires space for critical reflection on our professional practice and space to identify learning and developmental goals that can equip us with new-found knowledge, skills and attitudes to support our maturing professionalism.

In the literature there is a clear message of what people value in the professional working relationship with practitioners (Lyons 2013). MacLeod (2008) notes that an effective practitioner is one who is experienced by others as a ‘friend’ and ‘equal’. Beresford et al. (2008) define those qualities as going the extra mile and sharing aspects of oneself, which are both important for relationship-based practice. Understanding oneself and sharing one’s life experiences can often be a powerful tool for effective change and validating the life experiences and trauma of people we support within the field of social care. Yet inappropriate self-disclosure can lead to the people we work with losing confidence in our abilities as social care workers. There is a fine line to walk between effective and ineffective self-disclosure of our own life experiences. As a rule, we should always review with a line manager the appropriateness of the self-disclosure prior to presenting it to those we work with.

Reflexive Activity for Self-Disclosure

Is the disclosure for the benefit of the client? What is the goal of me sharing my experience? How will this self-disclosure benefit the person I am working with? Am I sharing my experience because the client’s story has resonated or triggered a response within me?

4. Self-Care as a Tool for Self-Discovery

All too often the last person a social care worker nurtures is themselves. Obstacles to self-care often manifest as a lack of energy or motivation, shouldering too many responsibilities and the unwillingness of the practitioner to appear vulnerable and seek help. The consequences of poor self-care can be detrimental not only to the worker, but to the clients and professional organisation in which one works. Failure to value the importance of self-care practices can result in emotional or

physical exhaustion – compassion fatigue – or vicarious re-traumatisation, which can ultimately lead to professional burnout and a practitioner leaving the field of social care. The development of a self-care plan will act as a protective factor against such issues. In effect one needs to provide space for peace and healing from the therapeutic relationship which you are holding and find ways to energise and thrive. Meeting one’s basic physical, mental and emotional needs through rest, nutritious food and adequate exercise is essential. Thereafter, finding ways to generate love, joy and happiness through relationships, hobbies and life adventures can help us energise. Recognising that a practitioner’s most foundational instrument is themselves should shift the focus from self-care being an afterthought to making it an essential element of one’s own wellbeing, which should be valued and nurtured.

Worksheet 1 Self-Care Action Plan

|

SELF-CARE ACTION PLAN |

|||

|

Communication and Connection Practices |

Rest and Relaxation Practices |

Survival and Stress Practices |

Health and Hobby Practices |

|

Current Practices: |

Current Practices: |

Current Practices: |

Current Practices: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

New Practices: |

New Practices: |

New Practices: |

New Practices: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

People who can support me: |

|||

|

Personal Goals |

|

|

|

Short-term (6 months) |

Medium-term (1-2 years) |

Long-term (3+ years) |

|

Professional Goals |

|

|

|

Short-term (6 months) |

Medium-term (1-2 years) |

Long Term (3+ years) |

Conclusion

Social care professionals are human beings who are as vulnerable as any other to the life events and challenges we are faced with. Each practitioner enters the field of social care bringing with them a unique sense of self and unique life experiences from which their world view is shaped. To this end, it is important that we spend time with the ‘self’ and come to understand the values and belief systems from which we operate. The self we bring to the people we work leaves a lasting impression on their life course. It is important therefore that we can truly empathise, connect and respond effectively to promote growth, healing and empowerment in others. Self-care and supervision are powerful tools that can provide a safe place for us as social care practitioners to explore and work through our own dilemmas while simultaneously refining the ‘self’ we bring to our therapeutic relationships. Additionally, the need for social care workers to share ideas and experiences in this area is pivotal for adding to the body of social care knowledge which students and practitioners can access and learn from.

References

Anda, R. F., Fleisher, V. I., Felitti V. J., Whitfield, C. L., Shanta R. D. and Willainson, D. F. (2004) ‘Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and indicators of impaired worker performance in adulthood’, Permanente Journal, Winter, 8(1): 30-8, doi: 10.7812/TPP/03-089.

Baldwin, M. (2000) The Use of Self in Therapy (2nd edn). Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Beresford, P., Croft, S. and Adsheal, L. (2008) ‘“We don’t see her as a social worker”: A service user case study of the importance of the social worker’s relationship and humanity’, British Journal of Social Work 38: 1388-407.

Cooper, A. (2012) ‘The Self in Social Work Practice: Uses and Abuses’, paper presented at the CSWP/ Essex University Day Conference, ‘How to do Relationship-based Social Work’, Southend, 13 January 2012. Available at https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/22204117/the-self-in-social-work- practice-uses-and-abuses-andrew-cooper

Dewane, C. J. (2006) ‘Use of self: A premier revisited’, Clinical Social Work Journal, 34(4).

Edwards, J. and Bess, J. (1998) ‘Developing effectiveness in the therapeutic use of self’, Clinical Social Work Journal 26(1): 89-105.

Harris, M. and Fallot, R. D. (eds) (2001) Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems. New Directions for Mental Health Services. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kaushik, A. (2017) ‘The use of self in social work: Rhetoric or reality?’, Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics 14: 1-21.

Lyons, D. (2013) ‘Learn about Your Self before You Work with Others’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

McLeod, A. (2010) ‘A friend and an equal: Do young people in care seek the impossible from their social workers?’, British Journal of Social Work 40: 772-88.

Rogers, C. (1957) ‘The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change’, Journal of Consulting Psychology 21, 95-103.

Schneider-Corey, M. and Corey, G. (2002) Groups: Process and Practice. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.