Chapter 60 – Adrian McKenna (D4SOP5)

Domain 4 Standard of Proficiency 5

Understand the importance of and be able to seek professional development, supervision, feedback, and peer review opportunities in order to continuously improve practice.

|

KEY TERMS Supervision Feedback Learning cycle Peer review opportunities Personal values

|

Social care is … a profession that allows us to use a personal connection to maintain trusting, caring and supportive relationships to help the vulnerable individuals that we work with grow, develop and be the very best version of themselves that they want or choose to be. |

TASK 1

Read Chapter 57 and write your own definition of professional development. List all the activities I completed as part of my continuing professional development.

Supervision

This chapter focuses on three main areas of professional development: supervision, feedback and peer review opportunities. To help you develop your practice, supervision is the tool that is at the core of what we do in social care. Having had the opportunity in the past to work with really experienced supervisors has certainly added to my professional practice. The abiding thing for me is when supervisors make you feel very safe, allowing you to express yourself honestly, which I believe is one of the first parts of the social care worker development process. If you are not honest with yourself, you cannot be honest with someone else and if you are not honest with someone else, it is not possible for supervisors to support you on your professional journey. Engaging in and taking responsibility for professional development in social care normally starts with the supervision process. The hope would be that you will have a well-trained, experienced social care professional as your supervisor, and part of your supervision would be your developmental process. The Tony Morrison model of supervision identified personal development as one of the four tenets of supervision.

The objectives and functions of supervision are described by Morrison as:

- competent accountable performance (managerial function)

- CPD (developmental or formative function)

- personal support (supportive or restorative function)

- engaging the individual with the organisation (mediation function) (Morrison 2005).

TASK 2

Register at www.hseland.ie and complete the PDP e-learning module.

This process requires you and your supervisor to collaboratively look at a personal development plan. In the first instance you look at where your development is currently; you do this by constructing a historical narrative around your education, experience and desires so that you can then look forward and identify the deficits in your practice, knowledge, skills and development. It can be a simple, straightforward process and there is plenty of support available to help you do this. The HSE have an e-learning module of professional development planning which is certified and can be completed in under an hour.

Feedback

Supervision is very much about feedback. The supervisor takes what they see, what they feel and what has been said to them in relation to your performance and feeds that back to you in a supportive, gentle and coaching way. An example of that from my career is summarised in the following case study.

Case Study 1

My supervisor said to me that he didn’t feel that I was very aware of the effect I could have on a room when I entered it. I wasn’t entirely sure what he meant by the comment and I asked him to explain it further. He then challenged me to explain what other people in a room might see when I enter. I gave a description of how I might appear to others, but I was very much off the mark. My supervisor explained that as a very big man, standing well over six foot, with earrings, tattoos, beard, bald head, the whole works, can appear quite intimidating. He continued: I didn’t actually need to say anything when I entered a room because my physical presentation was being interpreted as intimidating. This comment resonated with me, especially from the time I worked in detention services and residential homeless services for young teenage boys. Based on their experience of the world, someone who looked like me was viewed as a natural threat, and therefore when I entered a room I could change the vibe of that room very quickly by just being there.

TASK 3

- How would you feel if you received this feedback in supervision? Discuss

- Have you ever received feedback from a supervisor that enabled you to ‘see’ yourself from a different vantage point?

- Describe how your own physical presence may be perceived by the different people we work with in social care.

This is how great supervision really helped me to understand that when I enter a space like that, I need to use my vocal, visual and caring skills very quickly to help calm that room space and change the misinterpretation of my physical presence. In my own practice as a supervisor I look to use the self in concrete examples in order to support learning for my supervisees. I will happily use positive and not-so-positive examples of my practice down the years to invite those I supervise to engage in their own narrative.

I supervised a social care worker in homeless residential service who was having difficulty asserting his leadership in a team setting. When we delved into the issue, they were struggling with the possibility of upsetting colleagues or being seen as not backing up a colleague. We looked at past examples of the times when I had peer reviewed his work skills and practice and how he felt afterwards. He was fixated on the ‘challenge’ aspect of communicating feedback to colleagues, viewing the process as entirely negative. When we explored this further, his internal narrative was focused on the feelings of ‘you have failed so now you get punished’. When I asked the supervisee to compare our feedback session with giving feedback to colleagues, he could see that I was doing the same thing with him, giving feedback, but using a learning, developmental process and analysing the experiences through the stages of experiencing, thinking, reflecting and acting.

Learning Cycle

I like to remind those I supervise of the value of Kolb’s learning cycle (Kolb 1984). Kolb showed us that the four stages in the ‘cycle of learning’ are the central principles of his learning theory. The ‘immediate or concrete experiences’ are the basis for ‘observations and reflections’; the ‘observations and reflections’ are then distilled into ‘abstract concepts’ which presuppose an action that can be ‘actively tested’, creating new experiences, which are observed and reflected upon. When you combine that model of supportive supervision with the concepts of servant leadership you have a caring supportive model that holds people accountable, but in a way that helps them to thrive in the supervision process and not be afraid of it.

Servant leadership is very much what it says – it is leading by serving. It has been said that servant leaders put the needs of others before themselves, which is a distinctly social care process. These leaders quietly nurture and support followers as they shift authority to them, which fosters follower confidence and personal development (Northouse 2016). When the servant leader’s goal is the shifting of authority and the strengthening of their peer(s), you can see how that would facilitate good, honest, robust feedback, leading to honest, supportive peer reviewing.

The peer review process is something that all social care workers should be comfortable with or at least open to. There are many models available, such as the 360-degree process, and these formal models can work if the team and the individual are open to the process. They are based on a series of questions that your peers have to answer honestly. Taking that feedback can be very, very challenging for you; but if you assume that if someone who is peer reviewing is being honest, well, then you have to look inside yourself and challenge yourself.

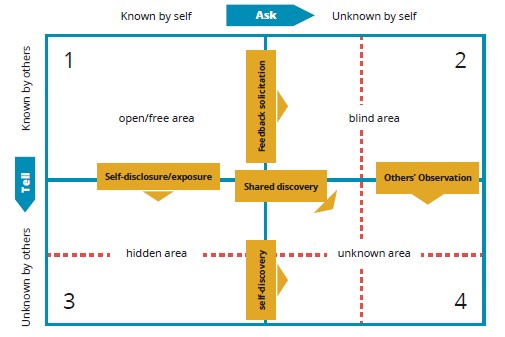

Peer Review Using the Johari Window

A particularly good tool to use when we are involved in this process is the Johari window (Chapman 2003). it is one of the few tools out there that has an emphasis on ‘soft skills’ such as behaviour, empathy, co-operation, inter-group development and interpersonal development. It is a useful model because of its simplicity and because it can be applied in a variety of situations and environments.

The Johari model has four quadrants. The first quadrant is your ‘open area’ – what we know about ourselves and are willing to share. This is where the trust in the working relationship is built, by disclosing to and learning about each other. As well as helping the individual, this strengthens a team. Then we have our ‘blind area’ – this is where someone in the group becomes aware of an aspect of us that we don’t recognise or refuse to see. With the help of honest feedback and supportive supervision we may be able to change some of these aspects. The third quadrant is the ‘hidden area’ – where we may actively try to suppress or hide aspects of ourselves from others. This is particularly challenging when you are exposing yourself to high levels of openness and honesty. Finally, the fourth and most challenging quadrant is the ‘unknown area’ – this is unknown to you and unknown to your colleagues. This quadrant can never become exposed if you do not engage honestly with others. The general premise is that over time the balance between the four quadrants can change. For example, if you decide to be more open with a colleague and tell them something you had previously kept hidden, this increases your open area and decreases your hidden area. It is also possible to increase the open area by seeking honest feedback from peers; this in turn can decrease your blind area. If the culture of an organisation allows for this depth of analysis in the supervision process, you will be working in an incredibly supportive caring team.

Professional development and a commitment to improving and developing your practice requires you to continuously challenge your sense of self. If we do not understand who we are, where we are, what triggers us, what keeps us happy, what makes us sad, what frightens us, what angers us, how we fit in a team; if we do not work on continuing professional development; if we do not look for continuous feedback in supervision – well, then we cannot continually improve our practice. In this case, what we are talking about is us having the ability to critically analyse our professional practice, and one way to do that is to develop a very strong working relationship within the supervision process. As social care professionals, we need to be mindful of the impact of our own personal values and life experience on the individuals we work with and for. Although one would believe that this in itself is a simple thing to do, it is by the very nature of humankind complex and in need of some consideration.

Personal Values

Personal values are the things that are important to us, the characteristics and behaviours that motivate us and guide our decisions. As an example, maybe you value honesty. You believe in being honest wherever possible and you think it is important to say what you really think. When you do not speak your mind, you probably feel disappointed in yourself. It has been suggested that it is from our early childhood experiences that we begin to form the core beliefs and values that influence the way we judge ourselves, others and the world at large (Beck 1995). In Ireland, and indeed worldwide today, anybody who is not a part of the hegemonic culture may find themselves being the victims of oppression and marginalisation. All sub-groups in society, whether they are ethnically diverse, religiously different, identify a different orientation or sexuality or are measured by economic strata, can attest to that marginalisation and oppression. As social care workers we only have to look at the public discourse surrounding the marriage referendum, the Eighth Amendment referendum and the continuing discourse in relation to the Traveller community and those seeking asylum in Ireland. With that being said, it does not take a huge leap of faith to assume that we as social care professionals may share those prejudices too. If we are influenced by our personal values that are formed by these prejudices rather than a professional value system, it could be potentially challenging for us to understand, work with and take part in an ethical decision-making process with any marginalised individuals, groups and communities. Moreover, we could contribute to social care becoming an element of oppression in a modern Ireland.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

Complete a Johari window task within the supervision setting. Ask the student to look at themselves using the four quadrants, and then you, as supervisor, do the same.

Look at a piece of work or a work-based scenario and ask the student to look at the scenario from a Kolb learning cycle perspective.

Look at understanding servant leadership and how it might work in a social care setting: https://www.greenleaf.org/what-is-servant-leadership/

What does supervision mean to you, the practice supervisor, and the student? Do you see the value in the process? See: https://www.iriss.org.uk/resources/insights/achieving- effective-supervision

References

Beck, J. (1995) Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York: Guilford Press.

Chapman, A. (2003) The Johari Window. Illustration included with the permission of the author. Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think. New York: Heath & Co.

Kolb, D.A. (1984) Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

Morrison, T. (2005) Staff Supervision in Social Care: Making a Real Difference to Staff and Service Users (3rd edn). Brighton: Pavilion.

Northouse, P. G. (2016) Leadership: Theory and Practice (7th edn). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Self Awareness (2013) ‘Understanding the Johari Window Model’. Available at <https://www.selfawareness.org.uk/news/understanding-the-johari-window-model>.