Chapter 66 – Helena Doody (D5SOP5)

Domain 5 Standard of Proficiency 5

Know and understand the principles and applications of scientific enquiry, including the evaluation of intervention efficacy, the research process and evidence informed practice.

|

KEY TERMS Research process Evidence-informed practice (EIP) Principles and applications of scientific enquiry Evaluation of intervention efficacy

|

Social care is … an ever-evolving integrated systems approach to working with individuals to help them lead a fulfilling and meaningful life. It places the person at the centre of the process and encompasses social justice and human rights principles. |

TASK 1

Describe something that you researched for yourself – it could be a holiday destination, a college course or a college/university where you wanted to study. How did you carry out your research? Why did you choose the final destination, college, university or course? What influenced your decision? Where did you look for information? What type of information did you look for and what did you find most useful in helping you to make a decision?

Research Process

Humans are naturally inquisitive; we are always trying to make sense of the world we live in. We do this by asking questions, seeking out new information and learning from our own experiences. We navigate life by experience, observation and the example of others, whether they are family, friends, or people we perceive as having authority through acquired knowledge and/or lived experience. The search for knowledge and truth is discovered by research. We all carry out research in some shape or form in our everyday lives and, while this may not be formally conducted, we are nonetheless continually seeking information on how best to achieve our goals and often enquiring how to get the best value for money. The value in conducting research prior to investing our time or finances is that we achieve a better outcome, greater opportunities and/or the best value possible.

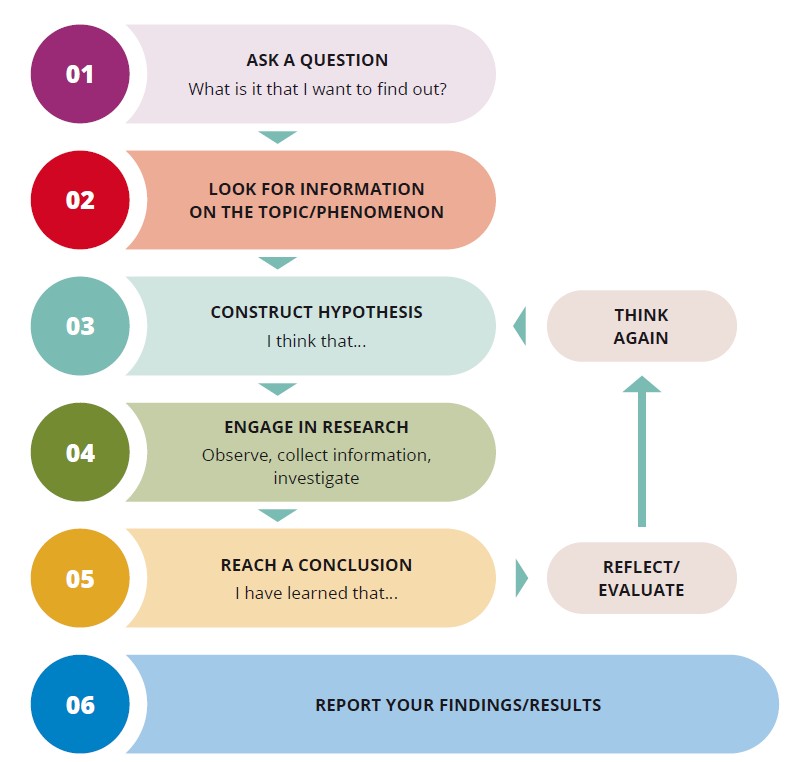

The following diagram outlines some of the questions one might ask and some of the steps one might take when conducting research.

When engaging in any form of research or developing interventions for service users, social care workers must act in accordance with and adhere to the Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics for Social Care Workers:

In all circumstances where consent is required prior to engaging in any assessment, intervention, treatment or service the following process must be followed:

- take personal responsibility for obtaining consent from the service user, or from someone with legal authority to give consent on the service user’s behalf

- ensure that, if you have to delegate to a colleague the responsibility for obtaining consent, such colleague is suitably trained and qualified to undertake this responsibility

- ensure as far as possible that the consent provided is voluntary and not the result of inappropriate pressure from a third party

- provide the service user with sufficient relevant information, in a way that s/he can understand, to enable the service user to decide whether or not to consent

- allow time and space, as far as possible, for the service user to take in and understand the information before reaching a decision

- answer any questions relating to the assessment, intervention, treatment or service from the service user honestly and as fully as s/he wishes

- respect the right of the service user to refuse consent to an assessment, intervention, treatment or service, even if you do not agree with their decision

- follow applicable law, regulation and guidance issued by appropriate authorities in relation to the giving of information and recording of the service user’s decision

- respect a service user’s advance healthcare directive in accordance with law, regulations and national policies or guidance. In emergency circumstances where it is not possible to obtain consent from the service user, you must

- provide treatment or other intervention where this is necessary to save life or avoid significant deterioration in the health of the service user (SCWRB 2019).

Ethics and ethical approval

Prior to engaging in research is it vital to apply for and receive ethical approval. If you are engaging in research as part of an education programme, your university or college will require that you engage with the ethical approval process. This is to ensure that the principles and practices of good research are being adhered to. The Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics for Social Care Workers (SCWRB 2019) outlined above must also be followed. Engaging in the ethical process and applying for approval can be a long process, but research cannot commence until approval from the relevant ethics committee has been obtained.

Miles and Huberman (1994: 290-7) refer to 11 ethical issue and dilemmas that one must consider prior to and during the research process:

- Worthiness of the research

- Competence boundaries

- Free and informed consent

- Benefits, costs, reciprocity

- Harm and risk:

- minimising harm (non-maleficence)

- maximising benefit (beneficence)

- Honesty and trust

- Privacy, confidentiality and anonymity

- Intervention and advocacy

- Research integrity and quality

- Ownership of data and conclusions

- Use and misuse of results.

There are approximately 32 health research ethics committees (RECs) in the HSE (Health Service Executive). Some approve research taking place in the organisation to which they belong; others have a regional remit and can approve hospital and community healthcare organisation (CHO) based research. Further information is available at https://hseresearch.ie/research-ethics/.

Tusla’s National Research Office is responsible for co-ordinating all research activity of Tusla (the Child and Family Agency). Further information is available at https://www.tusla.ie/research/ tusla-research-office/about-the-national-research-office/.

Evidence-informed practice

Engaging in reflective practice assists social care workers in evaluating both their individual and organisational relationships and practices. This in turn informs key decision-making in social care practice provision, which ultimately impacts on service users’ experience.

Evidence-informed practice (EIP) underpins, informs and shapes how the social care profession delivers effective services. Engaging in EIP is a key component in social care and helps to ensure that the mistakes and shortcomings highlighted throughout the history of social care are not repeated. EIP can assist in problem-solving and in preventing harmful procedures and interventions that negatively affected service users (Aveyard and Sharp 2009). The aim of research is to learn about a phenomenon in order to create improved outcomes and meaningful life experiences. EIP first emerged in healthcare and more recently has been adopted by social care. It is used as a research method in social care to support best practice and deliver the best possible care.

It Indicates an approach to decision making which is transparent, accountable and based on careful consideration of the most compelling evidence we have about the effects of particular interventions on the welfare of individuals, groups and communities (MacDonald 2001: xviii).

As suggested by Rosen (2003), a growing evidence base emanating from the implementation of evidence-based practice can guide the development, implementation and evaluation of new programmes and practices.

EIP gathers data and information that suggest whether a particular practice or intervention is working and therefore having successful outcomes in an individual’s life. Research aims to help provide the most effective services based on the best available evidence that offers service users the best possible outcomes alongside enhanced life experiences. As professional social care workers, we are accountable, therefore; we must have a clear rationale for engaging in particular practices and interventions. We must ensure that our practice is informed by reliable evidence that this is the best way of providing services and addressing the needs of the individuals we are supporting. We must be able to justify and provide a clear rationale for the practices we are engaging in.

The benefits of engaging in EIP include:

- Promotes value and addresses service user needs

- Informs the development of education of the profession and social care service delivery

- Highlights the importance of developing and using research in generating new knowledge and evidence as well as a commitment to improving services and outcomes for service users.

Person-centred planning is a good example of how engaging in EIP enhances service user participation and quality of life (Rogers 1961).

Case Study 1

Thomas is a 34-year-old man living in a residential home in a large organisation providing services to persons with a disability. Thomas has presented with behaviours that challenge, and these behaviours have resulted in him being considered not suitable for independent living. Thomas’s key worker introduced person-centred planning and worked with Thomas to identify and achieve personal gaols and aspirations. During this process Thomas was provided with strategies to communicate his needs and wants and to self-regulate. This resulted in a reduction in the frequency of the behaviours. As Thomas gained more control and independence the behaviours dramatically reduced. A direct correlation was made with the behaviours and lack of choice of control within his daily activities and wanting a meaningful life.

Thomas was referred to speech and language therapy to develop his communication skills. He also participated in an advocacy group and developed the skills needed to advocate for himself and express his opinions on how he wants to live his life. Thomas’s progression was evident in the development of his most recent person-centred plan. Thomas identified that he would like to work towards becoming more independent in his daily life. In particular, Thomas highlighted that he would like to move out of the group home and live in an apartment on his own. This goal presented some challenges, and both Thomas and his key worker faced challenges, including financial issues and accessing suitable housing. To gain more knowledge and to explore how living independently would work, Thomas and his key worker attended a workshop on self- directed living. This gave him a great insight into how independent living can work successfully for a person with an intellectual disability. Thomas has started to put plans in place to gain the skills he will need to live independently in the community. He has learned to manage his finances and is learning to use public transport. He is in the process of securing an apartment to rent in the local town, and has been working with his key worker to build up practical living skills like cooking, cleaning and budgeting, with a view to working towards his first overnight stay in the apartment on his own.

Thomas’s key worker also acquired new skills as he attended a course which focused on empowering the individual and on supporting persons to live independently. He used this learning to facilitate Thomas to have more choice and control over the way he wanted to live his life, and to encourage Thomas’s circle of support to identify their role in supporting him to achieve his goals. He also engaged in inter-agency collaboration to access resources to help Thomas achieve his goals.

Principles and applications of scientific enquiry

The word science is derived from the Latin phrase de scienta, which means ‘to know’. Inquiry is the search for information and explanation. It is also referred to as the ‘search for truth’. To engage in scientific inquiry is to study our world or a particular phenomenon and, based on the evidence of the research, to offer explanations. The aim of scientific enquiry in social care is to test the effect of interventions and to evaluate their success or otherwise. It is an approach to problem-solving by exploring and developing ideas that are based on scientific evidence.

There are many different ways to engage in scientific enquiry. The basic steps are listed below. It is important to note that this process can be cyclical; one may have to repeat the steps to reach a conclusion or workable solution.

Evaluation of intervention efficacy

TASK 1

Think of something you have researched and invested time and finances in.

Ask yourself: Was the outcome what I expected? Would I invest time and money in it again? Would I recommend the experience/value to family or friends? Would I choose the same service/option again?

In asking these questions, you are evaluating the service you received to ascertain if you achieved the outcome intended or if there are better options/services available. Therefore, you are evaluating the effects of the chosen intervention. In social care work, we must evaluate our practices and ask the questions: Are our services and intervention working? Are our service users and stakeholders satisfied with our approach? Can we do better?

Efficacy evaluation involves assessing the effect an intervention has on a service or service user/s. Engaging in efficacy evaluation and reflective practice is a key component in social care work and helps reduce the risk of harm. We need to demonstrate how services are making a difference. Questions that services and social care workers must ask of themselves are: Why are we/Why am I doing things this way? Is there evidence to suggest this is the best approach or are there more effective ways of doing this? Is there evidence of research that has been carried out, to review the efficacy of the intervention/approach? Are we valuing people’s experience?

National and international comparisons can be made on goal setting, inspection, reviewing and evaluation. There are many ways to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention. Enquiring as to the effectiveness, impact and quality of the intervention is key in evaluating efficacy. It is vital that social care workers and services engage in reflection and evaluation of services and interventions. Evaluation provides feedback on the effectiveness of the intervention and determines if it is appropriate for the service users or intended population.

In order to receive funding and satisfy funders and policy makers, the social care profession requires evidence that services are achieving their stated aims and that their interventions are making positive changes in providing meaningful experiences and supporting service users in their day-to-day living.

We have highlighted the importance of evidence-informed practice and research which provides a platform for service users’ and social care workers’ voices to be heard. However, further research is required to provide a better understanding of the relationship between research and the work of social care workers, including what organisational resources are needed to realise the aim of using research to shape practice. Third-level education programmes promote research at undergraduate and postgraduate level; however, access to participants and navigating gatekeepers can be challenging. This proficiency needs to be supported by service providers. Senior management must promote CPD by allocating resources to facilitate social care workers to engage in part-time education programmes that will enhance practice and improve services. A multi-agency inter-collaborative approach is required to create a research culture and encourage social care workers to engage in research that will unravel structures and systems and identify gaps in service provision.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

Engaging in research can be challenging for students. The terminology used can be off-putting. Exploring research carried out on a regular basis and breaking down the terminology can allay some of these fears and expectations. Educators can play a key role in supporting and developing a culture of research by encouraging students to:

- Engage with peer-reviewed research papers for continuous assessment

- Critically evaluate research carried out historically. Identify gaps in ethical procedures and dilemmas

- Identify evidence-informed practice

- Participate in research. This will provide an opportunity to be the participant as opposed to the researcher

- Carry out small research projects while in a placement setting (if permitted).

References

Aveyard, H. and Sharp, P. (2009) A Beginner’s Guide to Evidence-Based Practice in Health and Social Care. New York: McGraw Hill.

Dawes M., Summerskill W., Glasziou P. et al. (2005) ‘Sicily Statement on evidence-based practice’, BMC Medical Education 5(1): 1-7.

MacDonald, G. (2001) Effective Interventions for Child Abuse and Neglect: An Evidence-Based Approach to Evaluating and Planning Interventions. Chichester: John Wiley.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis (2nd edn). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ritchie, J. and Lewis, J. (2008) Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London: Sage.

Rosen, A. (2003) ‘Evidence-based social work practice: Challenges and promise’, Social Work Research 27(4), December 2003: 197-208, https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/27.4.197.

Rogers, C. (1961) On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2019) Social Care Workers Registration Board code of professional conduct and ethics. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at https://coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for- social-care-workers.pdf.

Tusla (2013) What Works in Family Support?, National Guidance and Local Implementation. Available at <https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/Tusla_What_Works_in_Family_Support.pdf>.

Virtual Library (website) <https://www.virtuallibrary.info/research-process.html> [accessed 20 September 2020].