Chapter 67 – Noelle Reilly and Denise Lyons (D5SOP6)

Domain 5 Standard of Proficiency 6

Demonstrate skills in evidence-informed practice, including an understanding of competing theories, concepts and frameworks underpinning social care work and demonstrate an ability to apply the appropriate method in professional practice.

|

KEY TERMS Evidence-informed practice SKIP model Skills in evidence- informed practice

|

Social care is … a process of working with people to support them to flourish and grow. Practice is based on the integration of relevant theories, concepts and frameworks underpinning the wisdom in evidence-informed practice. |

Evidence-informed Practice

The Standards of Proficiency for Social Care Workers (SCWRB 2017) require workers eligible to register to apply an evidence-informed approach to practice (D3 SOP6 – Chapter 6), to evaluate evidence- informed practice (D5 SOP5 – Chapter 66) and finally, in this proficiency, to be able to demonstrate this knowledge as skills. ‘Evidence-informed’ is a term commonly used in social work literature as a way of reducing the practice-knowledge gap (Kelly et al. 2010). This definition of the term is applicable here as there is an acknowledgement within our proficiencies that social care graduates will need to know competing practice theories, enabling them to choose from a range of responses for each experience they encounter. Evidence-based practice is evidence based on research, which is when the worker develops theory based on the collection of data. Nevo and Slonim-Nevo (2011) described evidence-informed practice as a more encompassing view of ‘evidence’. As well as including theory based on research, this view also accepts the value of the worker’s practice stories, and their informed decision-making experiences and judgements. Thus, evidence-informed practice takes a broader view of what constitutes evidence. According to Nelson and Campbell, evidence-informed practice includes ‘multiple strategies, processes and activities, which will vary depending on the purposes to be achieved, the contexts of practice, the availability of evidence, the individuals and/or organisations involved’ (Nelson & Campbell 2017: 131). As CORU stresses the role of evidence, it is essential for students, workers and educators to understand what constitutes ‘good’ evidence and the difference between evidence-informed practice (EIP) and evidence-based practice (EBP), which is also mentioned in the standards (D3 SOP9 – Chapter 49).

|

Evidence-informed Practice (EIP) |

Evidence-based Practice (EBP) |

|

An approach to interventions with clients or service users that utilises research evidence in conjunction with knowledge derived from other sources (e.g., practice wisdom and service user preferences) when identifying an appropriate intervention to meet their needs. |

An approach to interventions with service users that is based on scientific evidence. Practice is supported by proven rationale. |

TASK 1

Please read Chapters 6 and 66 when you have read this chapter for a greater understanding of an evidence-informed approach and how to evaluateevidence-informed practice.

Lewis (2001) defined knowledge as evidence plus practice wisdom (knowledge obtained in practice) plus service user and carer wishes and experiences. Lewis’s definition suggests that best practice in social care incorporates evidence-informed practice coupled with other salient factors. Therefore, practice is informed by evidence, but evidence is just one element (Shlonsky & Stern 2007). Holm (2010) supported this definition, but argued that organisational context, and organisational policies, procedures and guidelines must also be considered as evidence-informed practice in social care. Similarly, Brady et al. (2016) advocated for the development of evidence-informed practice as an approach that facilitates the practitioner to utilise research evidence in conjunction with knowledge derived from other sources when deciding on a course of action to support the service user. The common thread emerging from these studies is the need for social care workers to assess the evidence and integrate it into practice, giving due consideration to contextual influences.

Before we look at what constitutes evidence-informed practice in social care, we will briefly explain the difference between theories, concepts and frameworks and how they underpin social care practice.

Introducing Theories, Concepts, Frameworks

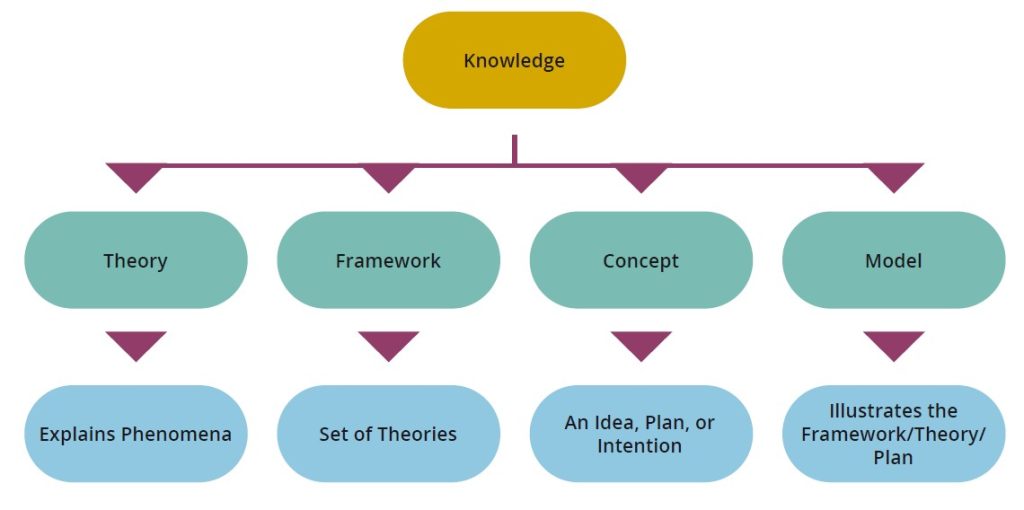

Social care practice is underpinned and shaped by various theories, concepts and frameworks. It is important that we have a critical understanding of theories that are significant in thinking about and practising social care work. In practice, social care workers critically engage with theories, reflect on their application to practice and consider their limitations. Relevant theories and concepts, when applied to social care work, have the potential to inform and improve practice. The following diagram highlights one key difference between a theory, a framework, a concept and model.

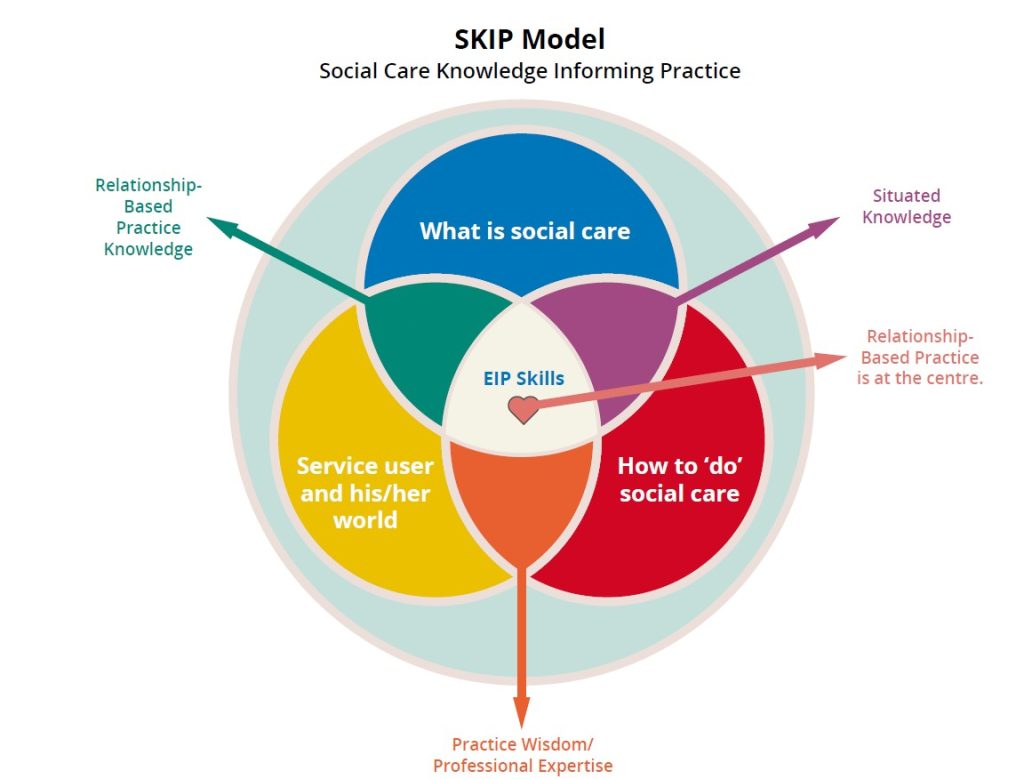

A theory is an idea or set of ideas that explains something (Stevenson 2010: 1829) and helps clarify a phenomenon, when we are trying to understand facts, experiences and situations. There are three categories of knowledge relevant to social care work: theories of what social care work is; theories of how to do social care work; and theories about the service user’s world. A concept is an abstract idea (Stevenson 2010: 358), which could be a new intervention or a plan for how to solve a problem that has not been tried before with a specific service user in the setting. A framework is a structure which underlies a set of theories or ideas (Stevenson 2010: 685), that are widely accepted, are based on evidence-informed practice, and can become guiding principles for practice within a particular discipline. Although not included in the proficiency, a model is a simplified description (Stevenson 2010: 1128) of an idea or theory used to help clarify the information or used as a method of illustrating or representing the framework. The knowledge base for social care is as diverse as the profession itself. Your formal social care education adheres to a performance strategy, for example the Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) Award Standards – Social Care Work (QQI 2014). Nonetheless, each programme differs in its structure and module composition. Each college/university has designed a suite of modules in each year of study to provide specialised evidence-informed knowledge and skills, underpinned by relevant theories and practice experiences. To help students understand the broad but interconnected knowledge bases for social care work, we have developed the SKIP Model (Social Care Knowledge Informing Practice) (Lyons & Reilly, forthcoming) to help clarify how the categories of knowledge and skills are equally valid and necessary for your holistic education.

SKIP Model – Social Care Knowledge Informing Practice

This model is evidence-informed (Lyons 2017; Reilly 2018). It aims to illustrate how all the knowledge needed to develop professional expertise in social care work is connected. The modules in your social care programme provide specific theories which contribute to one or more categories of knowledge. As you progress, these theories are woven together to become your integrated tapestry of skills and knowledge for professional practice. The SKIP Model (Lyons & Reilly, forthcoming) was designed to communicate the interrelatedness of evidence informing knowledge and skills, illustrating this ongoing process where you are both student (learning from new experiences) and teacher (sharing knowledge and skills gained) at the same time. This model is divided into three broad categories of knowledge, information, skills and experiences that help us understand (a) what social care is; (b) how to do social care and (c) all about the people we work with and their lived experiences, including the contexts of care in which we work and live together. How these three categories of knowledge overlap are defined as ‘situated knowledge’ and ‘practice wisdom’, with an understanding that the relationship between the service user and the worker is at the core of it all.

SKIP Model

Social Care Knowledge Informing Practice

Knowledge Base: What is Social Care?

‘Social care’ is a term used to define a milieu of care-based work with ‘vulnerable’ or ‘marginalised’ people in society. In most cases, social care workers are the professionals who work on the floor, sharing daily life events with people, in either residential or day services. Social care is historically linked to institutionalised care for children in industrial and reformatory schools (O’Doherty 2003) and Church-run services for children or adults with a disability (Finnerty 2013). The profession has broadened to include new domains. such as: child and adolescent mental health; addiction; services for people who are homeless; and community/family support. The foundational knowledge for social care is provided in your formal education on your social care degree programme. Here the combination of theoretical and practice-based modules are thoughtfully designed to provide the breadth and scope required for best practice in a variety of social care settings.

We included a section in each chapter entitled ‘Social care is …’ to provide a snapshot of how each social care worker in this text defines social care work, based on their lived experience of practice. The following are some examples of what the workers deemed social care is …

- About meeting people at a particular stage in their lives and supporting them to overcome their challenges and assist them with reaching their goals (Chapter 31 by Garreth McCarthy).

- Supporting people to live their best lives and reach their full potential through meaningful, person-centred interaction; supporting people to empower themselves through non-judgement and advocacy; encouraging and respecting the choices people make; and ensuring respect and dignity for the people we support at all times (Chapter 23 by Lynn Leggett).

- Being an extra support to a person in their time of need, being their information box, a spokesperson for them, a cheerleader behind them (Chapter 16 by Moira O’Neill).

- When I am asked what social care is, I tend to give the same answer again and again. It is about relationships (Chapter 38 by Des Mooney).

- An opportunity to harness human connection and spirit in a structured and purposeful way with the intention of improving the lives of others (Chapter 17 by Lauren Bacon).

The key themes in this random sample are supporting others to overcome challenges and live their best life; and relationship – making a purposeful connection with a person in their time of need.

TASK 2

Pick three other chapters and write down the key themes social care workers discussed in their ‘Social care is’ section.

Situated Knowledge

The knowledge required for social care practice is context-specific, shared and learned through mutual engagement and communication. Workers establish the knowledge base within their setting, which is negotiated, exchanged and emphasised between the members of the staff team (Wenger 1998). This is first experienced as a student on placement when you are guided by the practice educator to learn the way social care work is specifically practiced in the service. Lev Vygotsky (1896- 1934) stated that all learning is influenced by the social and cultural context in which it occurs. The central premise of Vygotsky’s work is that learning occurs through social interaction, mediated by physical and symbolic tools which are used to interact with the environment (Vygotsky 1978). These tools are passed from one social care worker to the next and are used to understand, engage in and ultimately change the ‘physical world’ of the service. In all social care settings, interactions happen through the use of tools, either psychological (language, practice stories, and relationships-based practices) or physical (universal records that everyone knows how to fill in, and the in-house policies). If social care workers move to a different setting they need to learn the policies, procedures and tools (physical and psychological) used there.

Social care services become situated learning spaces, similar to ‘communities of practice’ (Lave & Wenger 1991, Wenger 1998). As a learning theory, ‘communities of practice’ is based on the following principles: (a) all people are social beings; (b) through learning from work colleagues, workers gain competencies; (c) knowing what to do ‘on the floor’ is a product of ‘active engagement in the world’ of practice (Wenger 1998: xvi). We are not trying to define social care settings as communities of practice, but to use this framework as a way of explaining evidence-informed knowledge and how students learn the theories, concepts and frameworks underpinning social care, inside and outside the classroom. The practice educator shares the knowledge that underpins their approach to social care work, called situated competencies (Wenger 1998). Social care workers attribute meaning to particular stories, approaches, tools and interventions, which supports their practice. Students and new employees learn these shared practices from the staff team. Shared practices may include the role of helping and supporting others, the practice of key working, and most commonly, how the relationship is viewed as central to practice (Lyons 2017). Within the service, competing theories, concepts and frameworks help workers to understand likes and dislikes; interpret communication cues; meet needs quickly and effectively; provide support appropriately, and how to be an advocate by communicating accurate information to others.

Knowledge Base: ‘How to Do Social Care’

The discussion on situated learning spaces explains why social care workers may perform different tasks depending on where they work. What social care workers ‘do’ is based on the service in which they work, the specific tasks, duties and policies which frame their day-to-day practice and the role they play within the multi-disciplinary team and management structure of the organisation. Due to the diverse nature of social care, with different service user groups in both day and residential contexts, the practice of care is defined and structured by the setting, which includes how the social care worker is identified and valued. This knowledge category also includes all the theories, facts and policies on how to care for others through a human rights-based approach. Importantly, understanding how to care for or do with others begins with self-awareness, pointing the reflective lens inwards to understand our values, judgements and biases and reason for entering social care (Lyons 2007, 2009).

Practice Wisdom

Practice wisdom is ‘a personal and value-driven system of knowledge that emerges out of the transaction between the phenomenological experience of the client situation and the use of scientific information’ (Klein & Bloom 1995: 799). This is the wisdom workers use. It is underpinned by theories, concepts and models of best practice (information) and shaped by the worker’s lived experience of being with the service user. Practice wisdom is evidence, based on the combination of theoretical understanding and common sense knowledge emerging from the engagement in practice (Dybicz 2015). The knowledge acquired on how to do social care work and care for others is applied to practice. This knowledge is part of the wisdom used to guide workers in knowing how to respond to the different situations they encounter each day. Practice wisdom includes knowing how to react at a moment’s notice to a sudden event or new behaviour. It is also evident in the preventive work that is done to meet ongoing needs, for example having the cup of tea ready, knowing a service user likes to sit down when they come in from the day service. Time with service users was viewed as the most important way for social care workers to develop practice wisdom as they transition from the inexperienced newcomer to the status of competent and present old-timer (Lyons 2017). The social care setting frames the practice wisdom experienced there, and this ‘situated knowledge’, when combined with practice wisdom, becomes professional expertise.

Professional Expertise

When defining a model for social work, Gambrill (2013) argued that practitioners can draw on their clinical expertise to integrate information regarding the individual client’s personal characteristics and preferences with external research findings, thereby establishing the best intervention to address their needs. In social care practice, this is professional expertise; the worker performs best practice, underpinned by an integration of relevant evidenced-informed theory and practice wisdom, all led by their in-depth relationship and understanding of the service users’ likes, dislikes and actions within the specific context of care. It is important to note that research is always evolving, and as new information becomes available, some research, ideas, concepts and practices become invalid. Consequently, all sources of evidence, from empirical research to practice wisdom, are valid and necessary to enhance the worker’s expertise in how to best support service users (Rycroft-Malone et al. 2004). The development of evidence-informed practice skills is dependent on the sharing of knowledge and experience between workers, educators and managers involved in social care practice. This process of ‘knowledge mobilisation’ promotes the co-creation of evidence derived from research studies by academics and students about practice, the situated knowledge and case studies from workers and managers in different practice contexts, the practice wisdom developed from many years’ experience of critical thinking and problem-solving. If social care workers are to demonstrate skills in evidence- informed practice, including an understanding of competing theories, concepts and frameworks underpinning social care work, they need to keep talking to each other, share their expertise and value equally the role of each professional in the creation of evidence-informed practice.

Knowledge Base: ‘Service Users and their World’

The people we work with are described in this text as ‘service users’, a term currently used to describe vulnerable or marginalised adults, children or young people requiring care and support. We also work with children, young persons, residents (homeless services), trainees (day services), to name a few of the different titles used. A central component of social care education is learning about the lived experiences (disability, deprivation, abuse, addiction, homelessness, mental health, among others) of the people we work with, including how they communicate (all behaviours, sounds, language and colloquialisms). Although your social care programme will provide in-depth knowledge on the possible impact of a variety of experiences, social care is person-centred practice and the people we have the privilege to work with are experts in their own life, needs and care. This knowledge category also includes all information relevant to the development of quality service provision and how over time improvements are made to ensure the provision of safe, accountable and person-centred practice.

Relationship-based Practice Knowledge

TASK 3

- Please read Chapter 69 for more information on ‘relationship-based social care practice’.

- Please read the case study and complete the task below to give you an exercise on how this theory can apply to social care work.

The relationship is what makes social care work distinct; it is the most important learning space in practice and this is why it is presented as the heart of evidence-informed practice in social care work. We provide care and meet needs through the relationship using our personality, our self and our relationship skills from the social care worker’s toolbox (Lyons 2013). The relationship between a worker and service user is meaningful (Digney & Smart 2014) and trusting (Howard and Lyons 2014). The relationship is the ‘core’ of this practice (Kennefick 2006; Lyons 2009). Developing a relationship requires the personal skills of engaging, remembering details about the person, actively listening without interrupting them, and remembering the things they love and little personal things about them (McHugh & Meenan 2013). Listening in for the rhythm of each service user and tuning in to where they are in their life is also important (Maier 1992; Digney & Smart 2014). Being cognitively engaged also includes concentrating on the person and ensuring that your thoughts remain present and focused on meeting their needs (Garfat et al. 2018).

Case Study 1

Mary is 15 years old. She is witty, kind and mischievous. When Mary was 11, her mother passed away and Mary entered residential care. Mary had a turbulent couple of years. This is Mary’s third placement and she has lived here since she was 13. She is settled and seems content. Mary has attempted to go to school but due to social anxiety has not been able to maintain her attendance. She is currently on an education programme that she attends at home and has demonstrated that she is very bright. She completes her school work daily under the guidance of a tutor, who is currently being funded privately by the residential service pending input from the Department of Education. The care team support Mary in her studies with copious supplies of tea and praise. For the most part she can study independently. Mary’s father is incarcerated. Mary is very close to her older brother. They spend a lot of time together; however, he has limited means and it is not possible for Mary to live with him on a more permanent basis. Mary visits her dad once a month and they have weekly telephone contact.

|

Reviewing the Case Study through the Lens of the SKIP Model |

|

Relationship-based practice knowledge: In the case study we know that Mary has the intellect to be successful in school, but that her social anxiety is preventing her from accessing an education. We know that she has tried to overcome her anxiety but has not been able to maintain her attendance in school. So the care team supporting Mary have found another way for her to attend school that does not cause her anxiety, thereby ensuring that she has an opportunity to achieve her potential. You may also note that the type of support Mary requires is emotional support, for example ‘tea and praise’. She needs the reassurance that she can complete the tasks asked of her, and the comfort that small gestures such as bringing her a cup of tea brings. These gestures tell Mary that she is important, that she matters, that her needs are to the forefront of decisions made and that people around her care about her. Mary will feel validated, heard and empowered through the actions both of the service that she is placed with and the team who work with her. |

|

Situated knowledge: Considering the knowledge that is informing the actions of the care team in the above scenario, this service places a strong emphasis on the importance of education and on the importance of supporting Mary’s relationship with her family. The practice of the team demonstrates the use of therapeutic interventions in how they support each of these components in Mary’s life (see Byrne 2013 for an exploration of therapeutic social care practice). The team are tuned into Mary’s likes and dislikes, her needs and wants, and her family dynamic. Such support will encourage Mary to maintain important relationships and to access her education. |

|

Practice wisdom: In the case study above, the care team are relying on their knowledge of various theories, for example: Ainsworth (1978), Becker (1963), Biestek (1953), Bowlby (1969), Goffman (1959), Rogers (1961) and Winnicott (1960), and coupled with their experience of working with Mary (is intelligent, finds tea comforting, can only study/learn in a positive nurturing environment, family are important to her) to inform their approach so that Mary’s needs are appropriately met in a way which is empowering and supportive. |

The SKIP Model and the Standards of Proficiency for Social Care Workers

The eighty standards of proficiency for social care workers are the threshold standards of practice set by the Social Care Worker Registration Board for safe and effective practice. The standards of proficiency provide statements indicating the knowledge and skills that all those who enter the register as a social care worker must have (SCWRB 2017). Your degree programme has been carefully designed to ensure that every student will, when they graduate, have demonstrated their achievement of the standards of proficiency for social care workers. Across the higher education sector, the various institutes will have taken different approaches in how this is achieved. However, every programme is evaluated by CORU and is subject to ongoing monitoring and auditing by CORU to ensure that each student meets the threshold prior to graduation. All eighty proficiencies are relevant to the three categories of knowledge in the SKIP Model.

TASK 4

Select two proficiencies that relate to each one of the three knowledge categories:

- What is social care?

- How to do social care work.

- The service user and his/her world.

Professional Skills in Evidence-informed Practice

As a social care student, you will need to demonstrate proficiency in the skills of evidence-informed practice. The SKIP Model is a framework providing examples of the knowledge underpinning social care work. Understanding and applying this model is confirmation of your skills in evidence-informed practice. Gambrill (2013) identified three key traits which, she argues, are necessary to effectively engage with and pursue evidence-informed practice. These are critical thinking, advocacy and clinical expertise. The SKIP Model has reframed clinical expertise into the section entitled Professional Expertise, and the other two skills – critical thinking and advocacy – are also ways to demonstrate your evidence-informed practice.

Critical Thinking

Gambrill (2013) argued that critical thinking is a key component to any practice that is based on evidence. According to Paul (1993), the specific intellectual traits that are essential for critical thinking to be effective are courage, integrity and perseverance. Finn (2011) suggests that there are four thinking styles that enhance the development of critical thinking capacity in workers:

- Open-mindedness – a disposition that is interested in finding new evidence, new ways of working and new ideas

- Fairmindedness – the capacity to take on board views, opinions and perspectives which may be in contradiction to one’s own previously held beliefs

- Reflectiveness – the individual’s willingness to take time to review any new information and to look at the advantages and disadvantages of each without accepting the first apparent solution

- Counterfactual thinking – the capacity to look at the research and the situation from a range of different perspectives and to endeavour to think through possible alternatives and outcomes.

TASK 5

Think of recent experiences where you practised (1) open-mindedness, (2) fairmindedness, (3) reflectiveness and (4) counterfactual thinking.

Advocacy

The second key trait is for the worker to be an effective advocate for their service user(s). There is consensus across the social care literature in Ireland that social care workers’ advocacy role encompasses the promotion of the needs of the client (SCWRB 2017), ensuring that clients have access to an advocacy service (HIQA 2017) and a preparedness to advocate for resources and services subject to the needs of the client (Tusla 2016). Incorporated in the advocacy role is the need to ensure that the supports to empower service users are in place; for example, scheduling meetings in venues accessible by public transport or being aware of the need to avoid professional jargon in meetings. Service users may also rely on the interpersonal skills of social care workers to empower them to engage with other professionals or in certain situations (Evans & Kearney 1996).

TASK 6

- Think of recent experiences where you were an advocate for a service user or family member.

- Read Chapter 75 and Chapter 37 for more information on advocacy.

Social care knowledge is always evolving, building on the work and expertise of social care professionals and lived experiences of service users. The SKIP Model emerged from our own evidence-informed research, where we interpreted theories, concepts and the practice experiences of social care workers to enhance our work as educators. This model will also evolve and develop as we learn more. As a social care student this model may be useful to help you demonstrate your skills in evidence-informed practice.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

- Ask the student to present the SKIP Model to the social care team, as a way of gathering information on the evidence different workers use to inform their practice.

- To support your team to demonstrate their knowledge of and skills in evidence-informed practice (Standards of Proficiency for Social Care Workers), create environments for workers to discuss the evidence (knowledge and skills) used in their practice.

- Give the student on placement a piece of action research to conduct under your supervision. Action research is an approach to research in which the worker is the researcher, and the research topic is an investigation into the worker’s own practice. Workers examine what they do, why they do it and what results they hope to accomplish. The purpose of engaging in such research is to enable workers to create new theories regarding how the research has impacted on their personal practice. Through engagement in the process of action research, day-to-day work practices can become transformed into theories, thereby expanding the research in the field of residential care.

- Critical thinking skills:

The following tips are aimed to support students on placement to engage with Finn’s (2011) four thinking styles.

a. Open-mindedness – a disposition that is interested in finding new evidence, new ways of working and new ideas:

TASK 7

Read the blog by Carol Dweck, ‘A Summary of Growth and Fixed Mindsets’ (https://fs.blog/2015/03/carol-dweck-mindset/) and discuss the impact of the growth mindset on your thinking.

b. Fairmindedness – the capacity to take on board views, opinions and perspectives which may be in contradiction to one’s own previously held beliefs:

TASK 8

Read Kendra Cherry’s article ‘Unconditional Positive Regard in Psychology’ (https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-unconditional- positive-regard-2796005) and consider how understanding self-worth develops a sense of fairmindedness.

c. Reflectiveness – the individual’s willingness to take time to review any new information and to look at the advantages and disadvantages of each without accepting the first apparent solution:

TASK 9

Reflect on the impact of one theory on how you practise social care. Discuss why you chose this theory and how it applies to practice in your service.

d. Counterfactual thinking – the capacity to look at the research and the situation from a range of different perspectives and to endeavour to think through possible alternatives and outcomes:

TASK 10

Discuss one research idea at a team meeting, provide two different approaches and brainstorm the possible alternatives and outcomes.

References

Ainsworth, M. (1978) ‘The Bowlby-Ainsworth attachment theory’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1(3): 436-8, doi:10.1017/S0140525X00075828.

Becker, H. (1963) Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. London: Free Press of Glencoe.

Biestek F.P. (1953) ‘The non-judgmental attitude’, Social Casework 34(6): 235-9, doi:10.1177/104438945303400601.

Bowlby J. (1969) Attachment and Loss Vol. 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Brady, B., Canavan, J. and Redmond, S. (2016) ‘Bridging the gap: Using Veerman and Van Yperen’s (2007) framework to conceptualise and develop evidence informed practice in an Irish youth work organisation’, Evaluation and Program Planning 66: 128-33.

Byrne, J. (2013) ‘Therapeutic Social Care Practice’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Digney, J. and Smart, M. (2014) ‘Doing Small Things with Great Kindness: The Role of Relationship, Kindness and Love in Understanding Challenging Behaviour’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons, Social Care: Learning from Practice. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Dybicz, P. (2015) ‘From person-in-environment to strengths: The promise of postmodern practice’, Journal of Social Work Education 51: 237-49, doi: 10.1080/10437797.2015.1012923.

Evans, D. and Kearney, J. (1996) Working in Social Care: A Systemic Approach. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

Finn, P. (2011) ‘Critical thinking: Knowledge and skills for evidence-based practice’ Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools 42: 69-72.

Finnerty, K. (2013) ‘Social Care in Services for People with a Disability’, in K. Lalor and P. Share, Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland, 3rd edn, pp. 286-308). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Gambrill, E. (2013) ‘Evidence-informed Practice’ in B. Thyer and C. S. K. Dulmus (eds) Developing Evidence-based Generalist Practice Skills. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Garfat, T., Freeman, J., Gharabaghi, K. and Fulcher, L. (2018) ‘Characteristics of a relational child and youth care approach revisited’, CYC-Online E-Journal of the International Child and Youth Care Network <https://cyc-net.org/cyc-online/oct2018.pdf> [accessed 1 June 2021].

Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday. Garden City, New York: Doubleday Anchor Books.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2018) National Standards for Children’s Residential Centres. Dublin: HIQA.

Holm, M. (2000) ‘Our mandate for the new millennium: Evidence-based practice’, American Journal of Occupational Therapy 54: 575-85.

Howard, N. and Lyons, D. (eds) (2014) Social Care: Learning from Practice. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Kelly, M., Morgan, A., Ellis, S., Younger, T., Huntley, J. and Swann, C. (2010) ‘Evidence based public health: A review of the experience of the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) of developing public health guidance in England’, Social Science and Medicine, September, 71(6): 1056-62.

Kennefick, P. (2006) ‘Aspects of Personal Development’ in T. O’Connor and M. Murphy (eds) Social Care in Ireland: Theory, Policy and Practice. Cork: CIT Press.

Klein, W.C. and Bloom, M. (1995) ‘Practice wisdom’, Social Work 40(6) (November): 799-807.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, J. (2001) ‘What works in community care?’, Managing Community Care 9: 3-6.

Lyons, D. (2007) ‘Just Bring Your Self’, unpublished MA thesis, Dublin Institute of Technology.

Lyons, D. (2009) ‘Just Bring Your Self: Exploring the Importance of Self-awareness Training in Social Care Education’, in P. Share and K. Lalor (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Sharry, J. (2013) ‘Learn about Your Self before You Work with Others’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Lyons, D. (2017) Social care workers in Ireland – drawing on diverse representations and experiences. PhD Thesis, University College Cork.

Lyons, D. and Reilly, N. (forthcoming) The SKIP Model: Social Care Knowledge Informing Practice. (publication planned 2022).

Maier, H. (1992) ‘Rhythmicity – a powerful force for experiencing unity and personal connections’, Journal of Child and Youth Care Work 8: 7-13.

McHugh, J. and Meenan, D. (2013) ‘Residential Child Care’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds) Applied Social Studies: An Introduction for Students in Ireland, 3rd edn (pp. 243-58). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Nelson, J. and Campbell, C. (2017) ‘Evidence-informed practice in education: meanings and applications’, Journal of Educational Research 59(2): 127-35.

Nevo, I. and Slonim-Nevo, V. (2011) ‘The myth of evidence-based practice: Towards evidence-informed practice’, British Journal of Social Work, September, 41(6): 1176-1197.

O’Doherty, C. (2003) ‘The future of social care: Providing services and creating social capital’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies 4(2): 59-63.

Paul, R. (1993) Critical Thinking: What Every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World, 3rd edn. California: Foundation for Critical Thinking.

QQI (Quality and Qualifications Ireland) (2014) Award Standards – Social Care Work. Dublin: QQI.

Reilly, N. (2018) ‘An Investigation into Evidence-based Practice in Residential Centres in Ireland’, unpublished MA thesis, Athlone Institute of Technology.

Rogers, C.R. (1961) On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Rycroft-Malone, J. et al. (2004) ‘What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice?’, Journal of Advanced Nursing 47(1): 81-90.

Shlonsky, A. and Stern, S. (2007) ‘Reflections on the teaching of evidence-based practice’, Research on Social Work Practice 17: 603-11.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Stevenson, A. (ed.) (2010) Oxford Dictionary of English (3rd edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Tusla (the Child and Family Agency) (2016) Proficiencies: Reflection Guide for Social Workers and Social Care Workers. Dublin: Tusla.

Vygotsky, L. (1978) Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (first published 1930). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Winnicott, D. W. (1960) ‘Counter-transference’, British Journal of Medical Psychology 33(1): 17-21.