Chapter 70 – Teresa Brown (D5SOP9)

Domain 5 Standard of Proficiency 9

Have a critical understanding of the dynamics of relationships between social care workers and service users and the concepts of transference and counter-transference.

|

KEYTERMS Dynamics Practice environment Transference and counter-transference Support/supervision First voice

|

Social care is … a profession where we endeavour to work in solidarity, no them and us. It is a relationship based on respect and empathy. |

Dynamics

A consistent area of agreement in social care practice is the acknowledgement that effective social care revolves around relationships. The Social Care Workers Registration Board (SCWRB) defines social care as a relationship-based practice through which a planned and purposeful provision of care, protection, psychosocial support and advocacy is provided (SCWRB 2017). Despite this recognition, reiterated in social care policies and literature, a certain amount of ambiguity exists on how relationships are practised. It is my view that the dynamics of social care relationship, the actual doing of relationships, warrants more visibility and discussion in both academic literature and social care policies. Although consideration must be given to variables such as gender, sexuality, culture and class that shape the complex dynamic of the social care relationship, the argument put forward in this chapter centres on the importance of locating our critical understanding of this proficiency in the current social care practice environment.

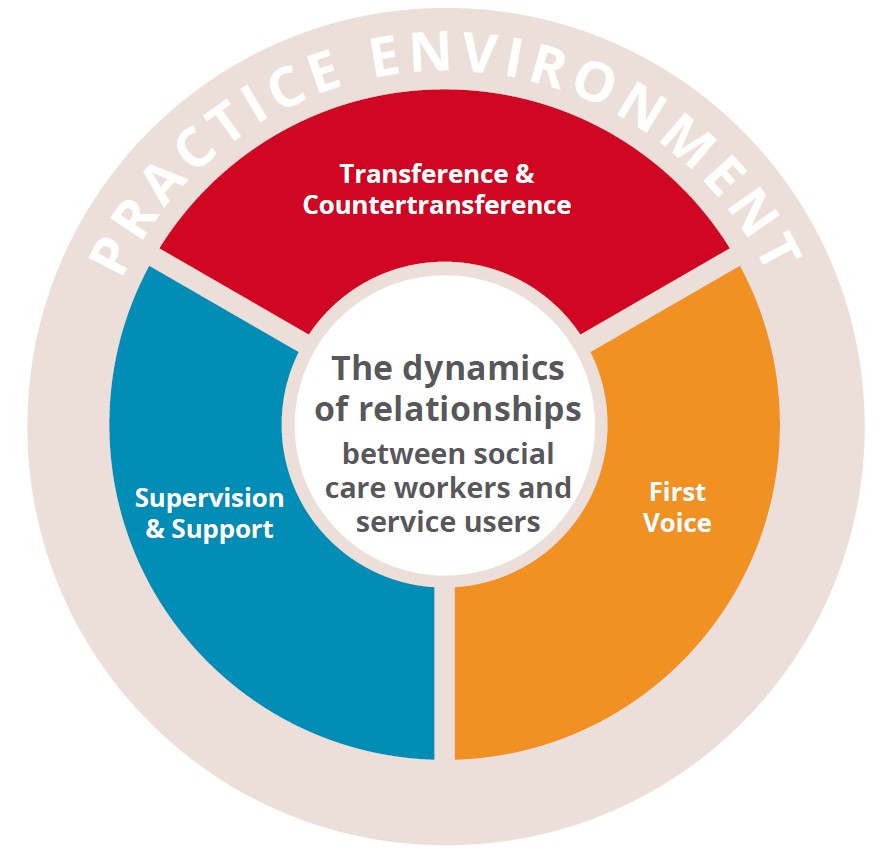

The model of the dynamics of relationship put forward in this chapter endeavours to capture some of the visible and invisible individual and structural dynamics that impact on the relationship between the social care worker and service user. These include:

- The Practice Environment: Arguably the practice environment is an unexamined component in the dynamics of the social care relationship. It is the backdrop to our practice, the organisation culture, which includes such things as ‘attitudes and beliefs, patterns of relationships, traditions, the psychosocial context in which work is done and how people collaborate in doing it’ (Menzies-Lyth 1990: 466-7). The practice environment is also shaped by legislative, social and economic influences, unconscious assumptions, attitudes and beliefs about the work task – the unspoken shared attitudes, the unacknowledged anxieties, conflicts, as well as the work atmosphere. The practice environment also includes the dynamics of multi-disciplinary and inter-agency practice, all shaping the dynamics of the social care relationship.

- Doing the Relationship: An understanding of the dynamics of transference and counter-transference in the social care relationship provides us with insight into service users and our own inner world. Using our first voice (Weick 2000) we can highlight the complexities of ‘doing the relationship’, advocating a move to work in solidarity, moving away from a ‘them and us’ attitude.

Supervision and Support: Supportive supervision practice allows us to reflect, self-analyse and respond to visible and invisible dynamics operating within the relationship as well as the complexities of the wider practice environment. Social care workers’ experience of support and being supervised is crucial to them being able to develop the capacity to recognise transference and counter-transference, individual and structural dynamics and the complexities of professional relationships.

The chapter begins with a discussion on the backdrop to all relationships; the practice environment.

Practice Environment

Against a backdrop of rapid societal and organisational change in the social care practice landscape, engaging in relationship-based practice presents challenges. The central argument based on research on relationship-based practice (Brown 2016) is that a culture of fear and risk underpins the practice environment, shaping knowledge, permeating the everyday norms and practices within the sector; and manifesting itself in the ways that relationships between social care workers and service users are constructed, experienced and lived out.

Discourses around ‘risk’ and a ‘risk society’ create the context in which fear emerges. Emotional responses to ‘risk’ and living in a ‘risk society’, it is argued, are designed to minimise and negate risks (perceived or real). Douglas notes that risk provides a powerful ‘forensic resource […] a language with which to hold persons accountable’ (Douglas 1999: 22), making it difficult for workers to work in risk-enabling ways due to fear of blame or liability (Ellis 2014) and in turn being held personally accountable (Furedi 2006; Gharabaghi & Phelan 2011). This can result in social care workers feeling fear in their daily experiences of practice (Smith 2009; Howard 2012). These fears can contribute to a climate where ‘not taking risks is positively advocated’ (Furedi 2006: 71) and where risk-taking becomes viewed as irresponsible behaviour and accidents the result of risk management failings. Consequently, risk is understood as a form of governmentality that undermines traditional practices of relationship-building (Furedi 2006).

Arguably social care workers’ responses to risk can be underpinned by anxiety and fear. The consequence of these fears and anxiety are manifested in relationships between social care workers and service users, where the main focus is often primarily on self-protection as the prelude for any professional interactions. In other words, staff and organisations have come to take their own safety as the starting point for ‘professional’ interactions (Steckley & Smith 2011: 84). It could be argued that this orientation has shifted relationship-based practice into a subsidiary of safe practice. In the context of daily professional practice where the relational aspects of the child-adult relationship, for example touch (Soldevila et al. 2013), have become the subject of regulation, constraint or have resulted in worker avoidance for fear of an allegation or complaint regarding improper, inappropriate and/or over-familiar contact. Steckley (2012) refers to these as the ‘damaging cultures of “no touch”’.

There has, and continues to be, much commentary in the literature on the impact of these regulatory and prescriptive procedures on professionals’ practice and the associated high levels of anxiety (Littlechild 2008; Brown 2016). Although the need to protect service users through improved regulation and inspection is viewed as a positive development, my research found that social care workers ability to develop and maintain relationships was constrained by bureaucratic requirements and the regulation of the relational space between workers and service users. Similar to recent criticisms in the literature (Smith 2009; Munro 2011; Howard 2012) reveal that regulatory responses were often in conflict with social care workers’ professional values and views on relational engagement. In some sectors of social care practice, relationships are now conceptualised in a way that is for utilitarian purposes of compliance (Murphy et al. 2013). This is where we can see the dynamics of the relationship between the social care worker and service user. In a national consultation with young people in care, ‘Listen to Our Voices’, one participant noted, ‘after the social care worker played a role in me being arrested, it was difficult to understand the relationship, as the next day they would be nice to me’ (McEvoy & Smith 2011: 18).

Maintaining relational engagement while following procedure-led practice can frequently undermine and impact on established relationships of trust; in fact, procedure-led responses have often reinforced and contributed to the escalation of challenging behaviour. The focus on managing behaviour primarily through procedure-led responses with no space for professional discretion and professional judgement can hinder the development of positive relationships. Despite an increased awareness of the need for organisations to create a relational-oriented culture, criticism continues to be levelled at adherence to a bureaucratic culture with regularised systems taking precedent over relational-oriented practice.

Multi-disciplinary/Inter-agency Practice

The challenge and complexities of multi-disciplinary and inter-agency practice have been consistently highlighted in the literature (Ferguson & Kenny 1995; Horwath & Bishop 2001; McWilliams 2006; Duggan & Corrigan 2009). The complexities of multi-disciplinary practice are evident in the daily experiences of workers, impacting on the dynamics of the relationship between social care worker and service user. In addition, the relational dimensions of social care can often place heavy burdens on service users, who are required to navigate relationships with a number of professionals. Navigating these relationships can be challenging, particularly when they experience poor inter-agency and multi-disciplinary practice. An example of poor inter-agency communication was noted in Buckley’s (2009) research: service users stated how they had to give the same information over and over again to different professionals whom they considered should be more connected to one another (Buckley 2009). Arguably, these kinds of experiences add further to the challenges service users are endeavouring to deal with.

Organisation structures in social care reflect an established hierarchy which is reflected in the way decisions are made. A number of social care workers feel their role and contribution are judged as lower in the hierarchy, and not sufficiently recognised and acknowledged in inter-agency working relationships (Brown 2016). The lack of shared responsibility is exacerbated by what Buckley (2003) calls the ‘exaggeration of hierarchy’. This refers to the privileged position afforded to the views of higher professionals such as psychologists over those of the workers who are in closest contact with children and families. The notion of the ‘closer to the child, the further from the decision’ was reiterated in the Brown (2016) study. Despite the regulations and official ideology emphasising the importance of professionals working together in meeting the needs service users, for some workers it is experienced as a discourse rather than a practice (Houte et al. 2013). It is argued that effective collaboration will only be achieved if efforts are made to articulate challenges, both long-standing and current. It is further argued that these challenges, if left unspoken, will continue to manifest in professional relationships and in the dynamics of relationship between service user and social care worker.

The poor quality of multi-disciplinary practice, or its failure to occur at all, has been identified in every inquiry report to date. Buckley (2009) highlighted that failings within multi-disciplinary practice reflect the dynamics between professionals and the tensions between and within agencies. She posits that these issues will not be solved with regulatory measures; they need to be addressed by supervision and capacity building within a supportive framework (Buckley 2009). With the reconfiguration of services, efforts have been made to promote multi-disciplinary practice with the establishment of collaborative structures and systems. However, as advised by Horwath and Morrison (2007), collaborative structures do not necessarily guarantee the realisation of collaborative activity; it is the informal relationships that are pivotal in inter-agency work, but they need to be supported by more formal linkages and acknowledged as an essential component of inter-agency practice.

Transference and Counter-transference

‘From a relationship-based perspective identifying conscious and unconscious constraints on practice responses is vital’ (Ruch 2009: 358).

This proficiency centres on the dynamics of relationship practice, focusing specifically on transference and counter- transference, terms associated with a psychodynamic perspective (McCluskey & O’Toole 2020). Transference and counter-transference are based on the tenet that an unconscious previous experience can influence the dynamics of the relationship process. Transference is a dynamic that happens in the relationship between service user and social care worker. Transference is when the service user unconsciously transfers feelings from another person/experience onto the social care worker. It is considered a form of projection, e.g., a previous negative experience of male relationship being transferred by a service user into the relationship with their male social care worker. Ruch (2012: 63) states that transference occurs when someone treats another person as if they were a significant figure from their past and behaves towards them as if they were that other person.

![A yellow sticky note pinned with a red pushpin. The note includes a definition of counter-transference in bold: Counter-transference “[U]sually refers to the therapist’s ability to note and make sense of emotions he or she is experiencing in the presence of the client and to consider these as important, if unconscious, communication from the client” (McCluskey & O’Toole 2020: 38). The quote explains counter-transference as a reflective tool in therapeutic or social care contexts.](https://tus.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/32/2025/04/Profesgewhy-300x300.png) Counter-transference is described as the inner emotional reactions of a social care worker to the service user’s transference. It can be a conscious or unconscious emotional reaction experienced by the social care worker. Counter-transference also refers to the social care worker independently transferring their own feelings to the service user. In our practice, we may encounter service users who have gone through similar experiences to us, for example the loss of a parent at young age. This can evoke emotional reactions in the social care worker, leading to counter-transference in practice.

Counter-transference is described as the inner emotional reactions of a social care worker to the service user’s transference. It can be a conscious or unconscious emotional reaction experienced by the social care worker. Counter-transference also refers to the social care worker independently transferring their own feelings to the service user. In our practice, we may encounter service users who have gone through similar experiences to us, for example the loss of a parent at young age. This can evoke emotional reactions in the social care worker, leading to counter-transference in practice.

The social care worker’s counter-transference reaction may manifest in certain types of behaviour, e.g., feelings of sadness on days you are engaging with the service user, becoming tearful when you thinking about the service user’s situation. The challenge for the social care worker is being effectively engaged with the service user in the moment, while also being sufficiently detached to identify what is happening in the transference or counter-transference as it emerges. This dynamic can often be difficult to understand and manage and social care workers can, in turn, find themselves reacting unconsciously.

In teaching students about transference and counter-transference, van Breda and Feller (2014: 470-1) utilised Sedgwick’s (2013: 108) idea of ‘cup hooks’ through the following analogy.

|

THE CUP HOOKS – EXPLAINING TRANSFERENCE AND COUNTER-TRANSFERENCE |

|

Imagine that you have cup hooks sticking out of your body. Lots of cup hooks. Each hook is something about who you are and what you have experienced. There are hooks for your gender, race, weight, education and town of origin. There are hooks for your experience of growing up as a lonely child, there are hooks for your views about your body image. |

|

As you practise the service user is constantly throwing out little lassoes – strings with a loop at the end. The service user throws them your way the whole time, unconsciously of course, their string is going to hook onto one of your hooks. When that happens, the service user ropes you in, establishing a connection, a relationship. |

|

Not only you, but the service user has hooks for all their characteristics and experiences. And you yourself are also throwing out strings and making connections. The relationship involves these unconscious connections, tapping into service users’ vulnerabilities and strengths. This is termed transference and counter-transference. |

First Voice

Consider this Quote:

‘Any developed theory of what counts for good practice should at least start with the hard-earned wisdom of its practitioners’ (Sinclair & Gibbs 1998: 115).

A key question is how we get beyond this to a position where the dynamics of the social care relationship are explored and understood at both micro and macro level. While the relationship has been broadly discussed in the literature, there is a need for further discussion on the dynamics of relationships; in a knowledge vacuum, relationships are considered a ‘largely empty word’ (Smith et al. 2013: 12). Arguably, because relationships do not sit neatly in an evidence-based intervention, and neither can they be scientifically measured, this could explain the lack of critical analysis on the conceptualisation and dynamics and reflect a view that relationships between workers and service users evolve organically. In conceptual and policy terms, positive relationships are recognised and valued; however, a current critical understanding is largely absent. Weick’s (2000) advice to social workers to avoid using their dominant professional voice and instead use their first voice, is relevant to the social care relationship. Within the social care field, excellent practice is not hard to find (Flynn 2020), but we need to make this visible. We need to continue to work in solidarity with service users, and distance ourselves from the ‘them and us’ attitude.

Furthermore, qualities and skills that make up relationship-based practice often remain invisible for fear of being negatively labelled as ‘over involved’ or ‘unprofessional’. It is this lack of fundamental recognition for all the elements that make up relationship-based practice (that is, use of personality in acts of individual and spontaneous kindness, humour; use of body through touching, hugging, comforting; and use of self as a social subject in the exercise of individual judgement, for example) that needs to be challenged and changed. In using our ‘first voice’, as workers we may move away from feelings of alienation and gain visibility and recognition in the wider context of practice. (Lack of visibility was particularly noticeable during COVID-19, with little acknowledgment in the media regarding the social care profession working at the coalface during the pandemic).

Part of the responsibility of social care workers in asserting their voice is not only to assert their experiences and views regarding best practice, but also to use their voice to challenge and change society’s perceptions of service users. We need to highlight that many of the challenges service users experience have origins in inadequate systems of support, e.g. education, housing. Inequality can manifest itself in different forms and impact a myriad of fields, such as employment, housing discrimination, education. For many service users whose trust has been abused in the past, either by a neglectful family or by a system that has failed to take their needs and wishes into account, ‘relationships are not easily constructed’ (Millham et al. 1986: 118). Past experiences of relationships often influence how we engage in current relationships (Cashmore 2002). These factors shape and influence the dynamics of the social care relationship.

There is one serious omission in the writings and reports on service users, despite the adversities they have experienced in their lives; they have an inner strength and sense of humour, which needs to be recognised in the literature. Professionals need to draw attention to their wisdom and resilience and policy makers need to learn from their lived experiences. Our recent Olympian champion Kellie Harrington’s brother encapsulated this when he stated that the area his family live in, although considered disadvantaged, is ‘one of the richest areas in the country because it is rich in support, camaraderie and community values’.

Going forward, it would be helpful if changes in the educational landscape could be effected to bring to the forefront, in training and teaching, themes such as ‘use of self’ and reflective practice, dynamics of transference and counter-transference within the wider ambit of relationship-based practice. A particular practical example of this, and following on from Anglin’s work (2015) on training, is to make workers aware of their own pain-based anxieties in order to be responsive rather than reactive. This will require course delivery that centres on tutorials and individual contact with the aim of increasing the level and quality of contact. Another way of enhancing training is through multi- disciplinary training, particularly on accredited courses. The training would require a strong focus on the ‘emotional dimensions of practice’ (Munro 2011: 91), which is probably best achieved by a combination of tutorial input and professional practice input.

TASK 1

Read the Listen to Our Voices report (McEvoy & Smith 2011), available as a free PDF from https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/139489?show=full.Q. Consider how you would address young people’s concerns with regard to relationship-based practice.

TASK 2

Read the Crisis, Concern and Complacency Report (Keogh & Byrne 2017), available as a free PDF from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312211150_Crisis_Concern_and_Complacency_A_Report_on_the_Extent_Impact_and_Management_of_Workplace_Violence_experienced_by_ Social_Care_WorkersQ. Reflect on the changes that have occurred as a result of the findings in the report.

TASK 3

Read Buckley et al., Service Users’ Perceptions of the Irish Child Protection System: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284722126_Service_User’s_ Perceptions_of_the_Irish_Child_Protection_SystemQ. In small groups, discuss how the service user’s views and experiences impact on dynamics between social care worker and service user.

Support/Supervision

‘The more we can create a space inside ourselves that has capacity to relate to where service users find themselves, the more effective we will be’ (Simmonds 2018: 235).

Working in systems governed by processes that are procedural, bureaucratic and have the tendency to enforcing regulations, emotional support for staff is identified as a prerequisite for the positive development of relationships (Trevithick 2014). The importance of social care workers being afforded reflective spaces and opportunities for reflective practice (Ruch 2007), in a supportive practice environment, cannot be over-emphasised. However, inadequate levels of support and supervision for front-line workers has been highlighted in every inquiry report to date. Within the context of supervision, in recent research by Keogh and Byrne (2016), social care workers articulated feeling a lack of emotional support, mainly from the wider organisation, with ‘supervision … never or only sometimes provided by management for the majority of social care workers’ (2016: 75). This is particularly concerning because regular professional supervision for social care workers is a statutory standard inspected and monitored by the relevant authorities.

A theme emerging in the literature is that supervision appears to be become skewed towards policy and procedural imperatives, rather than towards reflection and professional development (Jones & Gallop 2003; Ruch 2007). Policies and guidelines clearly articulate the importance of regular supervision; however, there is a tendency in the literature to focus primarily on providing regular formal supervision. The relationship between workers’ engagement at supervision in terms of their feelings of value is given insufficient attention. This can mean that unexplored fears and anxiety that can manifest in the day-to-day practice of relationships remain unexplored, thereby affecting the day- to-day effectiveness of relationship-based practice. It is argued that the emotional climate (Ward 2010) needs considerable attention to enable workers to process feelings (Sharpe 2008), understand the dynamics of transference and counter-transference and embrace the emotional elements of practice (Trevithick 2014). We need to create a practice environment that is characterised by respect, safety, trust and openness, which we can mirror in our relationship with service users.

|

Reflections on Transference and Counter-transference in Practice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

The pivotal argument in this chapter centres on recognising and addressing the contextual factors at the organisational levels (practice environment) that impact on the dynamics of the relationship between social care worker and service user. Social care’s remarkable strength as a profession is our persistence and commitment to relationships in practice environments that can be challenging and complex. We need now to create openings and opportunities to ensure that we are no longer at the periphery and contribute to a practice-based body of knowledge on the dynamics of the social care relationship.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

- Placement experience is usually students’ first opportunity to experience relationships in practice. Students need to be encouraged to use their reflective diaries to record their feelings and views on relationships in their practice placement.

- Practice educators can observe the student engagement in relationships with service users and the staff team and use these observations as discussion points in supervision.

- Practice educators have a pivotal role in supporting the student by creating a safe space in supervision for the student to explore their vulnerabilities and supporting them in identifying tools to recognise and manage transference and counter-transference patterns.

- It is important to highlight that the student’s supervisory experience can be a prototype of how relationships with service users should work.

- Fenton’s (2015) SOS model of relationship-based self-care incorporates three forms of relationship that the students can explore and use as an agenda for supervision sessions. These are: relationship with Self; relationship with Others; relationship with the System.

- Practice educators can provide direction with regard to self-care practices students can adopt.

- How a social care worker can build a relationship with someone who does not one to engage is an area that warrants discussion. Involuntary service users and defensive relationships are a part of social care day to day practice. Support the student in acknowledging and understanding the presence of difficult emotions in the dynamics of hostile relationships.

References

Anglin, J. P. (2002) Pain, Normality and the Struggle for Congruence: Reinterpreting Residential Care for Children and Youth. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Beddoe, L. (2010) ‘Surveillance or reflection: Professional supervision in “the risk society”’, British Journal of Social Work 40(4): 1279-96.

Brown, T. (2016) ‘Residential Workers’ Views of Relationship-based Practice’, unpublished doctoral dissertation, School of Social Work, Queens University, Belfast.

Buckley, H. (2003) Child Protection Work: Beyond the Rhetoric, London and Philadelphia, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Buckley, H. (2009) ‘Reforming the child protection system: Why we need to be careful what we wish for’, Irish Journal of Family Law 12(2): 27-32.

Buckley, H., Whelan, S., Carr, N. and Murphy, C. (2008). Service Users’ Perceptions of the Irish Child Protection System. Dublin: Stationery Office. Available at <https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/284722126_Service_User’s_Perceptions_of_the_Irish_Child_Protection_System>.

Cashmore, J. (2002) ‘Promoting the participation of children and young people in care’, Child Abuse and Neglect 26(8): 837-47.

Douglas, M. (1999) ‘Risk as a forensic resource’, Daedalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 119: 1-16.

Duggan, C. and Corrigan, C. (2009) A Literature Review of Inter-Agency Work with a Particular focus on Children Services. Dublin: Children’s Acts Advisory Board.

Ellis, K. (2014) ‘Professional discretion and adult social work: Exploring its nature and scope on the front line of personalisation’, British Journal of Social Work 44: 2272-89.

Fenton, M. (2015) Social Care and Child Welfare in Ireland. Dublin: Liffey Press.

Ferguson, H. and Kenny, P. (eds) (1995) On Behalf of the Child: Child Welfare, Child Protection and the Child Care Act (1991). Dublin: A. and A. Farmar.

Flynn, S. (2020) ‘Proficiency within professionalisation: A social constructionist critique of standards of proficiency for social care workers in the Republic of Ireland’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies 20(2): Article 6. Available at <https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijass/vol20/iss2/6>.

Furedi, F. (2006) Culture of Fear Revisited. London and New York: Continuum.

Gharabaghi, K. and Phelan, J. (2011) ‘Beyond control: staff perceptions of accountability for children and youth in residential group care’, Residential Treatment for Children and Youth 28(1): 75-90.

Houte, S., Bradt, L., Vandenbroeck, M. and Bouverne-De Bie, M. (2013) ‘Professionals’ understanding of partnership with parents in the context of family support programmes’, Child and Family Social Work 20(1): 116-24.

Horwath, J. and Morrison, T. (2007) ‘Collaboration, integration and change in children’s services: Critical issues and key ingredients’, Child Abuse and Neglect 31(1): 55-69.

Howard, N. (2012) ‘The Ryan Report (2009): A practitioner’s perspective on implications for residential child care’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Sciences 12(1): 38-48.

Howarth, J and Bishop, B. (2001) Child Neglect Is My View Your View, North Eastern Heath Service Executive and University of Sheffield.

Jones, J. and Gallop, L. (2003) ‘Protecting the reflective space’, Child Abuse Review 12(2): 101-6.

Keogh, P. and Byrne, C. (2017) ‘Crisis, Concern and Complacency: A Report on the Extent, Impact and Management of Workplace Violence experienced by Social Care Workers’, Social Care Ireland, doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.30702.41289.

Littlechild, B. (2005) ‘The stresses arising from violence, threats and aggression against child protection social workers’, Journal of Social Work 5(1): 61-82.

McCluskey, U. and O’Toole, M. (2020) Transference and Counter-transference from an Attachment Perspective: A Guide for Professional Caregivers. Oxford: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

McCulloch, S. J. (2021) ‘Keeping the “heart” in practice: The importance of promoting relationship- based practice in practice learning and assessment’, Journal of Practice Teaching and Learning, 17(3): 82-114. Available at <https://journals.whitingbirch.net/index.php/JPTS/article/view/1520>.

McEvoy, O. and Smith, M. (2011) Listen to Our Voices! Hearing Children and Young People Living in the Care of the State. Department of Children and Youth Affairs. Dublin: Government Publications.

McWilliams, A. (2006) ‘The Challenges of Working Together in Child Protection’ in T. O’Connor

and M. Murphy (eds), Social Care in Ireland: Theory, Policy and Practice (pp. 185-98). Cork: CIT Press.

Menzies-Lyth, I. E. P. (1990), ‘A Psychoanalytical Perspective on Social Institutions’ in Trist, E.

and Murray, H. (eds), The Social Engagement of Social Science, The Socio-Psychological Perspective Volume. London: Free Association Books.

Millham, S., Bullock R., Hosie, K. and Haak, M. (1986) Lost in Care: The Problems of Maintaining Links between Children in Care and their Families. Aldershot: Gower.

Munro, E. (2011) The Munro Review of Child Protection. Final Report: A Child-Centred System. London: Stationery Office.

Murphy, D., Duggan, M. and Joseph, S. (2013) ‘Relationship-based social work and its compatibility

with the person-centred approach: Principled versus instrumental perspectives’, British Journal of Social Work 43(4): 703-19.

Murphy, M. (1996) ‘From prevention to “family support” and beyond: Promoting the welfare of Irish children‘, Administration 44(2): 73-101.

Ruch, G. (2007) ‘Reflective practice in contemporary child-care social work: the role of containment’,

British Journal of Social Work 37: 659-80.

Ruch, G. (2009) ‘Identifying “the critical” in a relationship-based model of reflection’, European Journal of Social Work 12: 349-62.

Ruch, G. (2012) ‘Where have all the feelings gone? Developing reflective relationship-based management in child-care social work’, British Journal of Social Work, 42 (7), pp.1315-1332

Sedgwick, D. (2013) The Wounded Healer: Counter-transference from a Jungian Perspective. London: Routledge.

Sharpe, C. (2008) ‘Residential child care can do with all the assistance it can get’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies 8(1): 30-50.

Sinclair, I. and Gibbs, I. (1998) Children’s Homes: A Study in Diversity (Living Away From Home – Studies in Residential Care), Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

Simmonds, J. (2018) ‘Relating and Relationships in Supervision: Supportive and Companionable or Dominant and Submissive?’ in G. Ruch, D. Turney and A. Ward (eds), Relationship-Based Social Work: Getting to the Heart of Practice (pp. 221-35). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Smith, M. (2009) Re-thinking Residential Child Care: Positive Perspectives. Bristol: Policy Press.

Smith, M. (2011) ‘Love and the child and youth care relationship’, Relational Child and Youth Care Practice 24(1): 189-90.

Smith, M., Fulcher, L. and Doran, P. (2013) Residential Child Care in Practice: Making a Difference. Bristol: Policy Press.

Smith, M. (2011) ‘Care ethics in residential child care: a different voice’, Ethics and Social Welfare 5(2): 181-95.

Soldevila, A., Peregrino, A., Oriol, X. and Filella, G. (2013) ‘Evaluation of residential care from the perspective of older adolescents in care. The need for a new construct: optimum professional proximity’, Child and Family Social Work 18(3): 285-93.

Steckley, L. and Smith, M. (2011) ‘Care ethics in residential child care: a different voice’, Ethics and Social Welfare 5 (2): 181-195.

Steckley, L. (2012) ‘Touch, physical restraint and therapeutic containment in residential child care’, British Journal of Social Work 42(3): 537-55.

Trevithick, P. (2012) Social Work Skills and Knowledge: A Practice Handbook (3rd edn). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Trevithick, P. (2014) ‘Humanising managerialism: Reclaiming emotional reasoning, intuition, the relationship, and knowledge and skills in social work’, Journal of Social Work Practice 28(3): 311.

van Breda, A. and Feller, T. (2014) ‘Social work students’ experience and management of counter transference’, Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 50.10.15270/50-4-386.

Ward, A. (2010) The Learning Relationship: Learning and Development ror Work: Getting to the Heart of Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Weick, A. (2000) ‘Hidden voices’, Social Work 45(5): 395-402.