Chapter 75 – Teresa Brown and David Power (D5SOP14)

Domain 5 Standard of Proficiency 14

Be able to identify and understand the impact of social care history, organisational, community and societal structures, systems and culture on social care provision.

|

KEY TERMS Institutionalisation and seclusion Professionalisation and deinstitutionalisation Secularisation, specialisation and accountability Crisis and change |

Social care is … in its simplest form, supporting, protecting and helping vulnerable people to maximise their potential. However, social care is not simple. It is a journey of growth and learning. A way of providing resilience, but also being resilient. It is a way to promote change in people’s lives. It encourages people to be real. It is caring and kind when things become difficult and teaches by example with patience, trust, care, self-love and courage. It is unconditional to the needs of others. It is holding the dreams and hopes of traumatised young people. Social care feels pain and understands the lasting hurt from childhood experiences, and from the past, both theirs and ours. |

Introduction

A complex interplay of socio-political and economic factors has impacted on the wider context within which social care provision has emerged and has been shaped and delivered. At the current time, there is a concerted effort to professionalise, specialise and regulate the sector with the aim of improving outcomes for children, young people and families. Central to this reform is the need to understand the impact of social care history, organisational, community and societal structures, systems and culture on social care provision. There is no doubt that there is a tendency to distance ourselves from our history, such was the scale of physical, sexual and emotional abuse suffered by children in institutions run by a range of religious orders which were funded and inspected by the Department of Education. However, as McGregor (2014) argues, we must move beyond feelings of shock and shame at the failings that have been exposed and learn from the problems of the past and from their specific contexts.

This chapter provides a brief history of the key developments in our social care history. While locating the discussion within this wider context, the primary focus will be on the history of care for children. Changing ideologies and discourses and their consequent positive and negative impacts on social care provision and policy are highlighted. The catalysts and constraints which have shaped social care provision will be discussed.

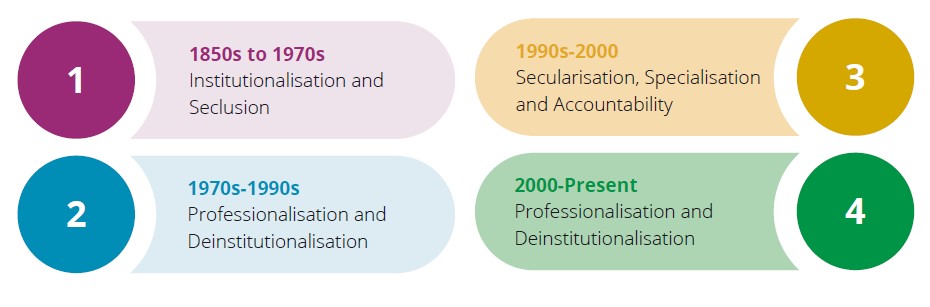

The emergence and development of residential childcare has been chronicled by Gilligan (2009) into three periods of development: institutionalisation and seclusion (1850s to 1970s); professionalisation and deinstitutionalisation (1970s to 1990s); and secularisation, specialisation and accountability (1990s-2000). To this, we have added a fourth category to denote developments from 2000 up to the present day. We have entitled this ‘crisis and change’, given the dominance of historical institutional abuse inquiries over this period, the challenges that have arisen and the changes that are emerging.

Institutionalisation and Seclusion

The first phase, from the 1850s to the 1970s, demonstrates Ireland’s unique socio-cultural composition. The development of policy was shaped by the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and the State remained at the periphery in all areas of residential care provision. Historical literature paints a picture of residential childcare as both positive and negative. On the one hand, thousands of destitute, orphaned and/or abandoned children received care, often for many years, and they were supported into adulthood (Barnes 1989). Thus residential child care played a pivotal role during a time of enormous hardship in Ireland.

On the other hand, writers also depict the geographical seclusion of these large institutions, isolated from the outside world, where contact with families was actively discouraged and, in some cases, prohibited (Barnes 1989). These practices were not criticised at the time because provision of residential childcare was underpinned by a ‘rescue model’ (Gilligan 1991) of childcare provision, where children were saved from unsavoury conditions. O’Sullivan (1979) depicts this model in his references to the Lord Chancellor’s speech in 1870 where childcare provision is described as ‘giving so many useful citizens to the State, so many immortal souls to heaven and rescuing thousands from lives of penury and sin who would have lived and died in crime and misery’ (O’Sullivan 1979: 211).

Reformatory schools were established by statute in 1858 for young offenders over the age of 12, in order to end the practice of sending young people to jail. Subsequently, the need for a different type of institution to cater for young people in need of care, and who were not offenders, was recognised. Ten years later the institution of the industrial school, first established in Scotland, Wales and then England, was extended to Ireland in 1868 after Irish parliamentarians advocated for its introduction (Craig et al. 1998). Industrial schools were described as schools ‘for the industrial training of children, in which children are lodged, clothed and fed, as well as taught’ (Children’s Act 1908, Section 44). Reformatory schools were defined in the same terms, but with the substitution of ‘youthful offenders’ for ‘children’ (Robins 1980). Despite being largely state-funded, these institutions were managed by religious orders (Raftery & O’Sullivan 1999), with the state adopting a subsidiary role in their management (Robins 1980), thereby allowing religious organisations to run the institutions without state interference.

The rescue model underpinned provision. It was informed by a social risk model of care, in which children were perceived as a social risk and a threat to society (O’Sullivan 1979) and the aim was therefore to mould males into hard-working working-class adults (Raftery & O’Sullivan 1999) and females into ‘the living embodiment of Our Lady – humble, pious, celibate’ (Inglis 1998: 248-9). Children were viewed as moral subjects, with the emphasis being on conformity (Smith 2007). Consequently, industrial and reformatory school systems were harsh regimes. However, it was only years later that it was realised just how harsh and cruel the were. The Church-State relationship constructed what Smith (2007: 45) terms ‘Ireland’s architecture of containment’, a term explained below. In addition to industrial and reformatory schools, there were other interdependent institutions, such as mother and baby homes and Magdalene laundries. Behind the walls of these institutions were members of society marginalised by a number of interrelated social phenomena including illegitimacy, incest and infanticide (Smith 2007).

In the mid-1850s, as an alternative to the state-owned, religious-managed facilities, voluntary organisations became involved in the provision of care for children. One such organisation was Mrs Smyly Homes. The founder of the organisation, Ellen Smyly, stated that in the 1850s it was nearly impossible to walk the streets of Dublin without being chased by children begging for pennies to buy food. Her first school opened in 1852 in Townsend Street. Smyly Homes began by providing education and accommodation for deprived children of Dublin, and it has maintained this value and approach to care.

TASK 1

Watch the YouTube clip ‘Courageous Campaigner – a tribute to Christine Buckley’.

Professionalisation and Deinstitutionalisation 1970-1990s

In 1970, the Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Reformatory and Industrial Schools’ Systems (which became known as the Kennedy Report) was published. It was generally viewed as a pivotal moment in childcare history. It set the course for the future development of childcare provision while also reflecting changes that were already afoot under several broad themes: deinstitutionalisation; diversification; regulation and professionalisation of the workforce.

With regard to deinstitutionalisation, by the time the report was published in 1970, the residential childcare system had greatly declined. Between 1964 and 1969, fourteen industrial schools were closed at the request of the religious orders. The decrease in the number of children in residential care and the increase in the use of foster care reflected both international trends and particular features of Irish society; fewer people were entering religious orders, and state finance to support voluntary and Church-based providers of residential childcare had been reduced (Buckley et al. 1997).

Although the process of the closure of industrial schools had already begun, the Kennedy Report reiterated the necessity of this, with Justice Kennedy being ‘appalled’ by their ‘Dickensian and deplorable state’.

Reiterating the recommendation of the Tuairim Report (1966) that staff should be fully trained in the various aspects of childcare, the Kennedy Report (1970: 13-14) also stated that the provision of trained staff should take precedence over any other recommendation and highlighted that ‘neither affection nor common sense is sufficient by themselves’. However, despite the positive support for the findings of the Kennedy Report, the Association of Workers with Children in Care expressed some reservations that a group model of care ‘could not provide for the majority now in need of care, the children with problems’ (1974, cited in O’Sullivan 1979: 45).

After the publication of the Kennedy Report in 1970, there were major changes in both child policy and practice. Subsequent policies and reports reflected and reiterated the view that residential care should be used only when no satisfactory alternative was available. Social workers were given primary responsibility for supporting families in need and placing children into care. This move was reflected in the Boarding Out Regulations (1983) which formally required a Health Board to place a child in residential care only where it was not possible to place him/her in foster care. Arising from the Kennedy Report, it could be argued that the positioning of residential childcare as an intervention of last resort was sanctioned and reinforced. On the other hand, the residential childcare sector continued to provide care for children and it was positively impacted by the growing emphasis placed on: understanding children’s needs; the workforce; and delivering care in a context where roles, responsibilities and regulatory frameworks were clear. For example, in relation to conceptualising and understanding children’s needs, the Kennedy Report depicted a shift in the discourse of the child. Smith (2007) highlights how these shifts in constructions of childhood were informed by scientifically informed conceptions of childhood, such as developmental psychology. A more positive view of childhood emerged during this era with developments depicting the recognition of a developmental model of care, replacing the ‘social risk’ model of childcare, whereby the child was seen as a potential threat to society rather than someone with needs and rights (O’Sullivan 1979).

![A yellow sticky note pinned with a red pushpin. The note contains a quote about the purpose of a course for Residential Childcare Workers: "The aim of the course was ‘to enable Residential Childcare Workers to cater for the basic living needs of children […] and be able to provide therapeutic care for those who are quite seriously disturbed’ (Brennan 1971: 5)." The quote highlights the dual focus on basic care and therapeutic support in early training for residential childcare professionals.](https://tus.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/32/2025/04/bhdsydy-300x300.png)

With regard to the workforce, the infrastructure of the residential care system was radically changed, with religious orders retreating from provision as a result of shrinking recruitment and an ageing profile in their congregations (Barnes 1989; Gilligan 2009a). As a result of this decline, lay personnel were employed in residential care centres. The decision to recruit lay staff effectively introduced the discipline of social care childcare in Ireland. Residential childcare workers employed in industrial schools were seen as purveyors of Church values and were expected to support the young people in their care to develop these values (Doyle & Gallagher 1996).

This strategy resulted in the continuation of an untrained workforce, as noted by the Kennedy Committee, which stated that there was ‘a tendency to staff the schools in part at least, with those who were no longer required in other work rather than with those specially chosen for childcare work’ (Kennedy 1970: 15). However, it is also within this context that positive moves towards professionalisation of the workforce also emerged. The first residential training course in childcare was initiated in 1971 in the School of Social Education, Kilkenny, signalling the start of the journey to professionalise residential childcare.

The significance of the move to professionalise the workforce, which gained further traction later, was that it signified an acknowledgement of the particular needs of children in residential childcare and challenged the view that children need only to be ‘lodged, clothed and fed as well as taught’ (Children’s Act 1908, Section 44). ‘House Parents’ was a title ascribed to the residential worker (Joint Committee on Social Care Professionals 2002) to reflect ‘normal’ family structures.

These positive outcomes of the Kennedy Report (1970) and reports from voluntary advocacy groups, including the Tuairim Report (1966), and Children Deprived: The Memorandum on Deprived Children and Children’s Services in Ireland (CARE 1972) were indicative of the move of the state from a peripheral position to centre stage in the delivery and organisation of residential care provision. Although positive developments were being made, challenges were still evident; for example, residential care was managed by three separate government departments until 2007, and there were concerns regarding broader governance arrangements as no single department had overall authority over or responsibility for children in care.

A further positive change was the establishment of the Task Force on Childcare Services in 1974. A year later it submitted its Interim Report, the recommendations of which focused primarily on the provision of additional residential services for Travelling children, young children, residential facilitates for boys and residential facilities for girls. One section of the report was dedicated to setting up on a pilot basis ‘Neighbour Youth Projects’ for children at risk. The common theme in the recommendations centred on residential services for young people who were described as ‘severely disturbed’ or young people ‘too difficult or disruptive for existing facilities’ (Task Force 1975: 9). In addition, identifying the training needs of residential childcare staff was considered a matter of urgency. Five years later the task force’s final report was published, as was a minority report reflecting the alternative views of two of its members (O’Cinneide & O’Dalaigh 1980).

Despite this progress, many subsequent developments reinforced the pervading discourse of residential childcare as a ‘last resort’. For example, the broader-based recommendations of the Task Force strongly favoured foster care and it emphasised the importance of prevention and community-based family services programmes. Furthermore, the report identified how this process could be achieved, suggesting that a specially trained worker could be instrumental in enabling some deprived children to continue living at home (DoH 1980: 21). Hence, in the early 1990s, this recommendation afforded opportunities for many residential workers to be appointed on multi-disciplinary teams in statutory services as community childcare workers, a title still used today. The importance of supporting residential workers was a dominant theme in the report.

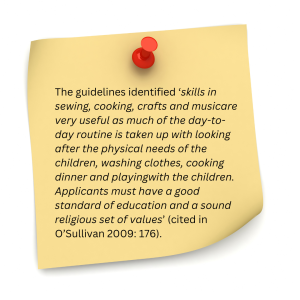

The Association of Workers with Children in Care, commenting in 1982 on the report’s recommendations, stated that ‘we plead loudly for our inclusion within a comprehensive plan’ (O’Sullivan 2009: 403). (Interestingly, this theme of seeking inclusiveness in policy formation is echoed today by Social Care Ireland.) Workforce issues continued to dominate this period. In November 1979, for example, guidelines on the recruitment of childcare workers were issued by the Resident Managers’ Association, the Department of Health and the Department of Education.

TASK 2

While the history of the children’s experiences is now on record, it must also be acknowledged that many carers had given great commitment, care, concern and warmth, mostly at great cost to themselves -unsupported, unacknowledged and in pretty impoverished conditions. There was no thirty-nine hour week, no salary scales and always a dearth of staff, especially men (Pat Brennan Director of first training course for social care workers).

Q. Reflect on what it was like to be a social care worker at this time.

Secularisation, Specialisation and Accountability 1990-2000

Developments during this period are best understood in the context of changing ideological, political and economic factors. As indicated earlier in this chapter, the development of childcare services up to this point reflected the positive and increasing recognition of the needs and rights of children, the need for specialist provision and the requirement for service delivery to be underpinned by a trained workforce. However, this was coupled with ongoing concern about the quality of day-to-day service delivery. In the 1990s, with the growing influence of neo-liberalism, the effect on the residential childcare sector was an increased emphasis on accountability, managerialism and bureaucratisation. These developments ran concurrently with an increased emphasis on the rights of the child.

Turning first to the rights of the child, from the early 1990s recognition of the need for changes in policy and practice in relation to children gained impetus (Nolan & Farrell 1990). In 1992, Ireland ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which provides a framework within which to develop and critique policies related to children. The conceptual paradigms of childhood were changing, with children’s needs beginning to be constructed more within a discourse of rights (Smith 2007). Developments in our legal framework provided further evidence of changing attitudes towards children. The Childcare Act 1991 replaced the Children’s Act 1908 after a gestation period of 25 years (Gilligan 1993), arguably indicative of society’s complacent attitude towards the welfare of children.

Specific changes in the Act included: extending the legal definition of a ‘child’ from the age of 16 to the age of 18, thereby prolonging the period of childhood; the introduction of a range of new orders, such as the emergency care order, which authorised the removal of a child or the retention of a child in the custody of the Health Board for a maximum period of eight days. Furthermore, an interim care order was introduced, this being a new short-term provision which could be made where an application for a care order was likely or pending. The care order committed a child to the care of a Health Board until their eighteenth birthday or for a shorter period. The Act also placed a statutory duty on Health Boards to provide family support, and set out the powers and duties of Health Boards with regard to children who were in their care. In addition, provisions under the Act required that consideration be given to the wishes of the child, having regard to the age and understanding of the child (Ferguson & Kenny 1995).

Monitoring compliance with the regulations was carried out by the Health Boards until 1999, at which time the Social Services Inspectorate (HIQA) was established on a statutory basis. The key area of change, as noted by Richardson (2005), following the passing of the Childcare Act 1991, was that there were increasing efforts to regulate and standardise procedures and practices in child welfare services.

Turning to neo-liberalism and the combined influence of discourses regarding accountability, managerialism and bureaucratisation, evidence of their hold on residential childcare provision can be seen in relation to the identification and management of risk (Webb 2006), with discussions ‘dominated by emotions of fear, an undermining of trust and the wish to control’ (Parton 2001: 69). This became evident in the broadening of the residential care landscape to meet the needs of young people considered ‘at risk’ or ‘a risk’. Consistent with previous studies, the overall picture that emerges from much of the research (Focus Ireland 1996; Craig et al. 1998; during this period centred on the difficulties of the residential care system in dealing with the ‘risk’ or the presenting problems of young people in their care. Arguably, insufficient attention was given to these challenges, which were repeatedly highlighted by residential workers over the years.

This situation escalated to the point that in order to secure a young person’s safety, applications were made to the High Court as a means of accessing placements. The High Court observed that Health Boards could not detain a young person for their own care and protection under the legislative provisions of the Childcare Act 1991 and therefore had to fill this legislative void (Carr 2007). With limited options available to the High Court, non-offending children were being routinely detained under court orders in Children Detention Schools, police stations, hotels, adult prisons, adult psychiatric hospitals and care institutions outside the state (Seymour 2006).

This response placed the Irish state in violation of its obligations under both domestic and international law and attracted much media attention and widespread criticism. However, it was the government’s inaction that provoked much critical commentary from the judicial system. The state’s lack of accountability to young people and families was the source of much criticism. The High Court repeatedly castigated the state for its failure to protect the constitutional rights of young people who came before the court (Whyte 2002). Commenting on the Health Board’s delay in providing secure accommodation, Justice Peter Kelly, in particular, gained national prominence for his criticisms of the system.

While these observations and concerns, cloaked in the discourse of risk, cast another shadow over the residential child care sector, revealing gaps in service provision, positive developments did emerge in the form of the establishment of special care and high support units. In general, the young people who came before the courts had been known to the Health Boards for several years. For some of these young people their histories highlighted a series of failed care placements, missed opportunities for professional interventions, and multi-disciplinary contact with families that had spanned a number of years. The extension and specialisation of the residential system to include high support and special care provoked much discussion and debate, with some favouring the development of a specialist resource and others querying the effectiveness of secure care in meeting the needs of young people and criticising the failure of the state to provide appropriate services and facilities to children with severe behavioural problems.

As a result, and in a context in which Ireland, from the mid-1990s onwards, was experiencing sudden economic success (the ‘Celtic Tiger’), various layers of accountability, managerialism and bureaucracy in residential childcare and in the form of policy and practice initiatives began to emerge. Delivering Better Government (DoHC 1996) outlined the government’s commitment to providing services that were accountable and transparent. There was a political view circulating that services would be more effective if managed like the private sector (Harvey 2011). Consequently, one of the central mechanisms of the Strategic Management Initiative (SMI) was the devolution of accountability and responsibility from the centre to executive agencies. The aim was to improve financial accountability and new systems obliged Health Boards to produce an annual service plan as well as to secure the ‘most beneficial, effective and efficient use of resources’ (DoHC 1996: 26).

At this time there were concerns about the number of social workers ‘leaving at an alarming rate due to high levels of stress and lack of appreciation of their role’ (McGrath 2000: 3). There was a sense that the budgetary framework was the primary focus of the accountability mechanisms in service management (O’Toole 2009). There were further calls for greater accountability and managerialism following the publication of the first major child abuse inquiry in Ireland, the Kilkenny Incest Investigation (McGuinness 1993). The report revealed the inadequacy of the Irish child protection system (Ferguson 1993) and has been described as catalyst for significant reform (Buckley & Nolan 2013). The report significantly changed the context in which policy and practice developed (Ferguson 1993). This report centred on a case of incest in which a young woman had been abused by her father over a 16-year period, during which time the Health Board had continued to be in regular contact with the family. In addition to expediting the implementation of the Childcare Act 1991, the report recommended the recognition of the rights of the child and the primacy of prevention and it called for constitutional reform so that the rights of the child were foregrounded and not subsumed within the marital family. This led to the subsequent constitutional amendment in 2012.

Three years later the first inquiry into residential care practice was published amidst legal discussions, with sections of the report omitted. This inquiry was established by the Sisters of Charity with the assistance of the Department of Health to review the operation of Madonna House, a residential centre in Dublin, in response to allegations of misconduct made against certain members of staff. It was suggested that ‘this report had brought residential care to its knees and to the forefront of the public domain’ (Dolan 1995:11), leaving a number of care workers from Madonna House ‘under a cloud of suspicion by association’ (O’Sullivan 2009). Then in 1999 an inquiry was called into Newtown House (SSI 2001), a residential centre that offered a high level of support in a secure setting, after a 16-year-old resident who had been absent without leave was subsequently found dead from a drug overdose. The report noted that there was a small number of trained staff, with high levels of sick leave due to stress and assaults, and a notable absence of professional supervision. The report concluded that staff were ‘working in an atmosphere of stress, fatigue and crises without adequate supports to guide their work’ (SSI 2001: 89).

As the impact of these reports was being processed, revelations of the ill-treatment and abuse suffered by children between the 1930s and 1970s in the reformatory and industrial schools system were highlighted in a three-part television documentary entitled States of Fear. Smith (2001: 23) describes how Raftery’s documentaries ‘excavated Ireland’s architecture of containment by focusing on the very people the structure was erected to deny’. Practices associated with the institutionalisation of children were now being exposed and the historical journey was being viewed through a different lens. It was inevitable that the States of Fear documentary, coupled with the Madonna House and Newtown House inquiries would create a sense of mistrust amongst the public regarding residential childcare provision.

The public were now more finely attuned to the sense that children were constantly in danger and as a result policies and guidelines were developed to reduce risk (Walsh 2013). The foundations, such as the introduction of the Child Abuse Guidelines in 1987, had been laid over the previous period (1970- 1980) for a professional system to respond to child abuse in the 1990s (Buckley & O’Nolan 2013). In 1999 the Children First Guidelines were published, but the application of these guidelines provoked much critical commentary, primarily due to a failure to impose them on a statutory basis, thus leading to inconsistency in their application (OMCYA 2008; Shannon 2009).

Crisis and Change – 2000 to the Present

By the year 2000, the conceptualisation of the child as a ‘rights bearer’ had gained much impetus and was articulated with the publication of the National Children’s Strategy (2000). This positive development marked a focus on rights-based language in policy development.

The National Children’s Strategy recommended an approach based on an ecological system practice orientation. In 2003, the first Ombudsman for Children, whose overall statutory mandate is to promote and monitor the rights and welfare of children, was appointed, and in 2005 of the Office of the Minister for Children (OMC) was established.

In this era, the Children Act 2001 was enacted, underpinned by the principle that detention should only be used as a last resort and that the focus should be on preventing criminal behaviour (O’Sullivan 2000). However, contradictions to the family support rhetoric were evident in the basic philosophy underpinning the Act that parents must be made responsible for the offences of their children (O’Sullivan 2000).

In general, the Children Act 2001 was viewed as a positive development, informed by the principle that detention should only be used as a last resort. The implications of increasing the age of criminal responsibility from 7 to 12 (subsequently amended to create two ages of criminal responsibility – 10 for most serious offences (murder, rape) and 12 for all others), meant that the Health Boards had responsibility for all children aged under 12 who came to the attention of the Gardaí. Practice was now located in the broader context of family support, and the importance of supporting families was a consistent theme in policy and reports, including the Agenda for Children’s Services (OMC 2007) . Arguably, the view that children’s welfare was generally best secured within the family setting was further consolidated by the public’s mistrust of residential care provision as a result of highly publicised inquiry reports.

In 2008, as a decade of prosperity ended abruptly, the government introduced a series of austerity budgets, which impacted on vulnerable Celtic Tiger populations (O’Toole 2009). This coincided with the Report of the Task Force on the Public Services, which recommended that publicly funded services needed to operate more efficiently and effectively, with more attention given to performance and delivery. Following a ten-year inquiry, the final report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse, commonly known as the Ryan Report, was published on 20 May 2009. The report contains harrowing accounts of the lives of children in institutions and details incidences of neglect and abuse – physical, sexual and emotional. Findings indicated that a climate of fear, created by pervasive, excessive and arbitrary punishment, permeated most of the institutions (CICA 2009).

The Ryan Report received international attention. The revelations of the nature and scale of abuse was particularly distressing; however, the cover-up by Church and state increased public indignation and provoked much critical commentary (Ferguson 2007, Stein 2008, Lee 2009, Ferriter 2010, Keenan 2011). The view that ‘children in care were from a lower strata and therefore unequal and less deserving’ (Lee 2009: 45) was evident in the commission’s quest to uncover the truth. It was often reliant on the efforts of survivors of child abuse and advocates to support it in the process.

The same year the government introduced the Ryan Report Implementation Plan (DoHC 2009), to which it allocated a budget of €15m. This positive development was quickly overshadowed by debates regarding the exact number of cases of children who had died in the care of the state between 2000 and 2010 being played out in the media.

TASK 3

Read the following article by Noel Howard: ‘The Ryan Report (2009): A practitioner’s perspective on implications for residential child care’, Irish Journalof Applied Social Studies 12(1), available at: http://arrow.dit.ie/ijass/vol12/iss1/4

The Report of the Independent Child Death Review Group (Shannon & Gibbons 2012) highlighted the deaths of children in care and identified missed opportunities where interventions, if available, could have made a difference to outcomes for young persons. They noted the most concerning finding from a public point of view when they concluded ‘that the majority of the children who are the subject of this review did not receive an adequate child protection service’ (Shannon & Gibbons 2012: 4).

In 2010, findings from the inquiry into the Roscommon case (Gibbons 2010) highlighted systemic failures that had been identified in earlier inquiry reports. Despite the endorsement since the 1990s of seeking the view of the child in all welfare policies and guidelines, the inquiry report (Gibbons 2010: 69) noted that the voice of the child in Roscommon case was ‘virtually silent’.

It is argued that these recent reports highlight the inadequacy of statutory services and demonstrate the continuities between historical practices and current responses to children in need. It was the impact of the successive inquiry reports, coupled with increasing calls from various groups (Constitution Review Group 1996, Children’s Rights Alliance 1997) advocating for the constitutionalisation of children’s rights, that eventually led to a referendum to insert a clause in the Constitution dealing with children’s rights.

Following an audit of existing aftercare services and consultations, the HSE introduced a national policy on leaving and aftercare services (HSE 2011). To ensure a co-ordinated approach in the delivery of services under the Childcare Act (1991) and the Children Act (2001) and in line with international developments, there was a concerted effort to involve young people in processes and procedures on decisions affecting their lives, coupled with support from advocacy groups such as Empowering Young People in Care.

The Ryan Report Implementation Plan (2009) stated that lines of responsibility and accountability for services delivered to children at risk were unclear, evidenced by the fact that there is no national out-of-hours social work service for children at risk or for children in care or their families. In 2011, there was a 50% cut in HSE staff training, despite the increase in caseloads and complex cases (Burns & MacCarthy 2012). At this time, the management structure of child protection and welfare services had been a source of consistent criticism.

Commentaries highlighted the dichotomy between ‘protection’ and ‘welfare’ and between ‘welfare’ and ‘justice’ (Smith 2005), which had been a recurrent concern in the literature. In addition to this orientation in practice, there were worryingly high thresholds for admission to the child protection system (Shannon & Gibbons 2012), which often delayed the provision of care for young people who needed it. Failures of multi-disciplinary communications (Duggan & Corrigan 2009) and increasing workloads were making it more difficult to engage with children in care (Lynch & Burns 2012).

In this context, change was eventually proposed in 2012 when a task force was established to advise on the preparations for the establishment of a child and family support agency on a statutory basis (DCYA 2012). Tulsa, the Child and Family Agency, is now the dedicated state agency responsible for improving wellbeing and outcomes for children.

Challenges continue to exist at the coalface of practice, with greater scrutiny, accountability for service delivery, and fear of ligation shaping the way services are delivered (Buckley & O’Sullivan 2007). These developments have led to a stronger emphasis on policies relating to accountability and performance. Accountability was further consolidated in 2012 with the publication of HIQA standards for statutory child protection social work departments. HIQA’s remit was now extended to the inspection of family and childcare services and to the development of standards.

This chapter concludes that despite efforts to rectify historical deficits, and despite positive developments in that direction, challenges remain. A common theme emerges that is a clear constant across each period of our history: the government’s attitude. This attitude is manifested in piecemeal reform, inaction and reactive responses to inquiry reports/controversies, which leads to policies being developed in times of crisis with fragmented solutions. Challenges articulated by advocacy groups, social care workers and cumulative committee recommendations have received limited attention. Consequently, knowledge has not been accumulated and there have been limited responses to challenges as they presented. There is clear evidence that demonstrates social care workers’ concern around the inadequacies of the system; however, it appears that change only occurs when situations are at crisis point or when there is a threat of litigation. Despite the evidence of discursive shift and consequent changes in service provision, gaps are still evident. One notable absence in the development of social care provision is the voice of the social care worker. The culture of accountability, although welcome, needs to be monitored in relation to its impact on day-to-day practice. The legal and risk management responsibilities of child welfare systems have shaped the overall orientation of our social care sector, this is an area that warrants attention in terms of the impact on relationship-based practice.

We need to continue to highlight gaps in service provision and endeavour to be part of a collective voice for social care reform. We must, however, remember that there are parts of our history we can be proud of; we need to learn from the important continuities of best practice and expertise built up over decades and recognise the commitment and dedication of past social care workers. To ensure the next chapter in our social care history is one to be proud of, we suggest the following areas need to be addressed.

|

Moving Forward to the Future of Social Care |

|

1 There is a need for the voice and experience of service users to be visible in policy formation and service delivery. These voices need to be not only heard but encouraged and fostered. |

|

2 Although the legal and risk management responsibilities of child welfare systems shape the overall orientation of our social care sector, we need to ensure that organisational structures and culture facilitate, rather than impede, positive outcomes for service users. |

|

3 Social care education and practice need to focus on the structural and institutional nature of oppression. |

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

- Discuss with the student the historical development of your agency. Set a task that supports the student in identifying the wider socio-economic and cultural contexts of social care practice.

- Support the student in documenting their views and understanding of social care history in their reflective diaries.

References

Barnardos (2000) Responding to the Needs of Troubled Children: A Critique of High Support and Secure Care Provision in Ireland. Dublin: Barnardos.

Barnes, J. (1989) Irish Industrial Schools, 1868-1908: Origins and Development. Blackrock, Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

Brennan, P. (1971) Course Outline: Childcare Course, (unpublished), Kilkenny.

Buckley, H. and O’Nolan, C. (2013) An Examination of Recommendations from Inquiries into Events in Families and their Interactions with State Services, and their Impact on Policy and Practice. Dublin: Department of Children and Youth Affairs.

Buckley, H., Skehill, C. and O’Sullivan, E. (1997) Child Protection Practices in Ireland: A Case Study. Dublin: Oak Tree Press.

Burns, K. and MacCarthy, J. (2012) ‘An impossible task? Implementing the recommendations of child abuse inquiry reports in a context of high workloads in child protection and welfare’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies 12(1): 25.

CARE (1972) Children Deprived; The CARE Memorandum on Deprived Children and Children Services in Ireland. Dublin: CARE.

Carr, N. (2007) ‘Young People at the Interface of Welfare and Criminal Justice: An Examination of Special Care Units in Ireland’. Centre for Social and Educational Research, Dublin Institute of Technology.

Childcare Act (1991). Dublin: Stationery Office.

Childcare (Amendment) Act (2007). Dublin: Stationery Office. Childcare (Amendment) Act (2011). Dublin: Stationery Office. Children Act (2001). Dublin: Stationery Office.

Children’s Act (1908). Dublin: Stationery Office.

Children’s Rights Alliance (1997) Small Voices: Vital Rights: Submission to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. Dublin: Children’s Rights Alliance.

CICA (Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse) (2009) Report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (Ryan Report). Dublin: Government Publications.

Constitution Review Group (1996) Report of the Constitution Review Group. Dublin: Stationery Office.

CORU, the Health and Social Care Professionals Council (website) <www.coru.ie>.

CORU/Regulating Health and Social Care Professionals (2012) Framework for Guidelines on the Standards of Education and Training, and Monitoring of Approved Programmes. Dublin: CORU.

Craig, S., Donnellan, M., Graham, G. and Warren, A. (1998) Learn to Listen: The Irish Report of a European Study on Residential Child Care. Dublin: Department of Education and Science.

DCYA (Department of Children and Youth Affairs) (2011) National Strategy for Research and Data on Children’s Lives 2011-2016. Dublin: Government Publications.

DCYA (2012) Report of the Task Force on the Child and Family Support Agency. Dublin: DCYA.

DES (Department for Education and Skills, UK) (2006) Working Together to Safeguard Children. London: HMSO.

DoH (Department of Health) (1980) Task Force on Child Care Services: Final Report to the Minister of Health. Dublin: Stationery Office.

DoH (1989) Report of the Commission on Health Funding. Dublin: Stationery Office.

DoH (1995) Child Care (Placement of Children in Residential Care) Regulations 1995. Dublin: Stationery Office.

DoH (1996) Report on the Inquiry into the Operation of Madonna House. Dublin, Stationery Office.

DoH (1996a) Child Care (Standards in Children’s Residential Centres) Regulations 1996 and Guide to Good Practice in Children’s Residential Centres. Dublin: Stationery Office.

DoHC (Department of Health and Children) (1996) Delivering Better Government. Dublin: Stationery Office.

DoHC (2000) Statutory Registration for Health and Social Care Professionals: Proposals on the Way Forward. Dublin: Stationery Office.

DoHC (2001) National Standards for Children’s Residential Centres, Dublin, The Stationery Office. DoHC (2001a) National Standards for Special Care Units. Dublin: Stationery Office.

DoHC (2002) Our Duty to Care: The Principles of Good Practice for the Protection of Children and Young People. Dublin: Government Publications.

DoHC (2009) Report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse, 2009: Implementation Plan. Dublin: Government Publications.

Dolan, P. (1995) ‘Innocent but never exonerated, guilty but never caught’, Irish Social Worker, 13 (1): 11. Dooley, R. and Corbett, M. (2001) Child Care: Juvenile Justice and the Children’s Act. Dublin: Children’s Rights Alliance.

Doyle, J. and Gallagher, C. (2006) In a Changing Ireland Has Social Care Practice Left Religious And Spiritual Values Behind: Proceedings of DIT Social Sciences Seminar, Dublin Institute of Technology, 3rd April 2006.

Duggan, C. and Corrigan, C. (2009) A Literature Review of Inter-Agency Work with a Particular Focus on Children Services. Dublin: Children’s Acts Advisory Board.

Fagan, S. (2009) ‘The Abuse and Our Bad Theology’ in T. Flannery (ed.), Responding to the Ryan Report (pp. 14-25). Dublin: Columba Press.

Fahey, T. (1998) ‘The Catholic Church and social policy’, The Furrow 49(4): 202-9.

Ferguson, H. (1993) ‘Child abuse inquiries and the report of the Kilkenny Incest Investigation: A critical analysis’, Administration 41: 4 (Winter): 385-410.

Ferguson, H. (1997) ‘Protecting children in new times: Child protection and the risk society’, Child and Family Social Work 2(4): 221-34.

Ferguson, H. (2003) ‘Outline of a critical best practice perspective on social work and social care’, British Journal of Social Work 33(8): 1005-24.

Ferguson, H. (2007) ‘Abused and looked after children as “moral dirt”: Child abuse and institutional care in historical perspective’, Journal of Social Policy 36(1): 123-39.

Ferguson, H. (2011) Child Protection Practice. Basingstoke and New York: Macmillan, Palgrave.

Ferguson, H. and Kenny, P. (eds) (1995) On Behalf of the Child: Child Welfare, Child Protection and the Child Care Act (1991). Dublin: A. and A. Farmar.

Ferguson, H. and O’Reilly, M. (2001) Keeping Children Safe: Child Abuse, Child Protection and the Promotion of Welfare. Dublin: A. & A. Farmar.

Ferguson, H. and Kenny, P. (eds) (1995) On Behalf of the Child: Child Welfare, Child Protection and the Child Care Act (1991). Dublin: A. and A. Farmar

Ferguson, I. and Woodward, R. (2009) Radical Social Work in Practice: Making a Difference. Bristol: Policy Press.

Ferriter, D. (2010) Occasions of Sin: Sex and Society in Modern Ireland. London: Profile Books. Fewster, G. (2001) ‘Growing together: The personal relationship in child and youth care’, Journal of Child and Youth Care 15(4): 5-16.

Fitzgerald, F. (2012) Launch of the Report of the Task Force on the Child and Family Support Agency, Friday 20 July. Dublin: DCYA.

Flannery, T. (ed.) (2009) Responding to the Ryan Report. Dublin: Columba Press.

Focus Ireland (1996) Focus on Residential Childcare in Ireland: Twenty-five Years Since the Kennedy Report. Dublin: Focus Ireland.

Gallagher, C. and O’Toole, J. (1999) ‘Towards a sociological understanding of care work in Ireland’, Irish Journal of Social Work Research 2(1): 60-86.

Garrett, P.M. (2014) ‘“The children not counted”: Reports on the deaths of children in the Republic of Ireland’, Critical and Radical Social Work 2(1): 23-41.

Gibbons, N. (2010) Roscommon Child Care Case: Report of the Inquiry Team to the Health Service Executive, 27 October 2010. Dublin: HSE.

Gibbs, A. (2001) ‘The changing nature and context of social work research’, British Journal of Social Work 31(5): 687-704.

Gilligan, R. (1991) Irish Child Care Services: Policy, Practice and Provision. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration.

Gilligan, R. (1993) ‘The Child Care Act 1991: An examination of its scope and resource implications’, Administration 40(4): 347-70.

Gilligan, R. (2000) ‘The key role of social workers in promoting the well-being of children in State care: A neglected dimension in reforming policies’, Children and Society 14(4): 267-76.

Gilligan, R. (2008) ‘Promoting resilience in young people in long-term care: The relevance of roles and relationships in the domains of recreation and work’, Journal of Social Work Practice 22(1): 37-50.

Gilligan, R. (2009) ‘Residential Care in Ireland’ in M. E. Courtney and D. Iwaniec (eds), Residential Care of Children: Comparative Perspectives (pp. 3-19). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gilligan, R. (2009a) ‘The “public child” and the reluctant state?’, Éire-Ireland 44(1): 265-90.

Government of Ireland (1936) Commission of Inquiry into the Reformatory and Industrial School System 1934-1936 (Cussen Report). Dublin: Stationery Office.

Government of Ireland (1937) Constitution of Ireland. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Government of Ireland (1999) Children First: National Guidelines for the Protection and Welfare of Children. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

Government of Ireland (2000) Our Children – Their Lives: The National Children’s Strategy. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Government of Ireland (2004) Childcare (Special Care) Regulations 2004. Dublin: Stationery Office. Harvey, B. (2011) A Way Forward for Delivering Children’s Services. Dublin: Barnardos.

Hayden, C. (2003) ‘Responding to exclusion from school in England’, Journal of Educational Administration 41(6): 626-39.

Hayden, C. (2010) ‘Offending behaviour in care: Is children’s residential care a “criminogenic” environment?’, Child and Family Social Work 15(4): 461-72.

Hayes, N. (2002) Children’s Rights – Who’s Right? A Review of Child Policy Development in Ireland. Dublin: Dublin Institute of Technology.

Hayes, N. (2006) Early Childhood Education and Care, A Decade of Reflection: 1996-2006, paper presented at the Proceedings of the CSER Early Childhood Education and Care Seminar Series, Dublin, 6 November 2006.

Health and Social Care Professionals Act (2005). Dublin: Stationery Office.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2013) Report on Rath na Óg Residential Centre. Dublin: HIQA.

HIQA (2013a) Overview of Findings of 2012 Children’s Inspection Activity: Foster Care and Children’s Residential Services. Dublin: HIQA.

HIQA (2015) Annual Report of the Regulatory Activity of the Health Information and Quality Authority: Children’s Services 2014. Dublin: HIQA.

Howard, N. (1997) Presidential address, Proceedings of Twenty-fifth anniversary of IACW, Annual Conference, Killarney, 5th November.

Howard, N. (2012) ‘The Ryan Report (2009): A practitioner’s perspective on implications for residential child care’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Sciences 12(1): 38-48. Available at <http://arrow.dit.ie/ijass/ vol12/iss1/4>.

HSE (Health Service Executive) (2011) National Policy and Procedure: Leaving and Aftercare Services. Dublin: Stationery Office.

IASW (Irish Association of Social Workers) (2011) A Call for Change, Discussion Document, Children and Families: Social Workers Make Their Voices Heard. Children and Families Special Interest Group, IASW.

Inglis, T. (1985) ‘The separation of church and state in Ireland’, Social Studies 9: 37-48.

Inglis, T. (1998) Moral Monopoly: The Rise and Fall of the Catholic Church in Modern Ireland. Dublin: University College Dublin Press.

Irish Justice Alliance (2004) Submission to the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform Project Team on the Irish Youth Justice System, Dublin, Children’s Rights Alliance.

Joint Committee on Social Care Professionals (2002) Final Report of the Joint Committee on Social Care Professionals. Dublin: Department of Social and Family Affairs.

Keating, A. (2004) ‘Church, state, and sexual crime against children in Ireland after 1922’, Radharc 5/7: 155-80.

Keating, A. (2014) ‘A contested legacy: The Kennedy Committee revisited’, Irish Studies Review 22(3): 304-320.

Keenan, M. (2011) Child Sexual Abuse and the Catholic Church: Gender, Power, and Organizational Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keenan, O. (2007) ‘The evolution of children’s services in Ireland and prospects for the future: A personal perspective’, Journal of Children’s Services 2(4): 71-80.

Kelleher, P. Kelleher, C. and Corbet, M. (2000) Left Out On Their Own: Young People Leaving Care in Ireland. Dublin: Focus Ireland and Oak Tree Press.

Kennedy, E. (1970) Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Reformatory and Industrial School Systems (Kennedy Report). Dublin: Stationery Office.

Lalor, K. and Share, P. (eds) (2009) Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Laxton M. and Laxton, R. (2008) A Review of the Future Requirements of Special Care and High Support Provision in Ireland: A Strategic Response. Dublin, Department of Health and Children.

Lee, M. (2009) ‘Searching for Reasons: A Former Sister of Mercy Looks Back’ in T. Flannery (ed.), Responding to the Ryan Report (pp. 44-55). Dublin: Columba Press.

Lynch, D. and Burns, K. (ed.) (2012) Children’s Rights and Child Protection: Critical Times, Critical Issues in Ireland, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

McGrath, K. (1993) ‘The effects on those at the heart of the Kilkenny Inquiry’, Irish Social Worker 11(4): 10-11.

McGrath, K. (1998) ‘New Irish research on children in residential care’, Editorial, Irish Journal of Social Work Research, 1(2), pp. 5-6.

McGrath, K. (2000) ‘New National Children’s Strategy high on aspirations, low on specifics’, Editorial, Irish Social Worker 18(2): 2-4.

McGregor, C. (2014) ‘Why is history important at moments of transition? The case of “transformation” of Irish child welfare via the new Child and Family Agency’, European Journal of Social Work 17(5):771-83.

McGuinness, C. (1993) Kilkenny Incest Investigation: Report Presented to Mr. Brendan Howlin T.D. Minister for Health. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Nolan, B. and Farrell, B. (1990) Child Poverty in Ireland. Dublin: Combat Poverty Agency.

O’Cinneide, S. and O’Dalaigh, N. (1980) Minority Report in the Task Force Report on Child Care Services. Dublin: Stationery Office

O’Connor, P. (1992) ‘Child care policy: A provocative analysis and research agenda’, Administration 40(3) 200-19.

O’Connor, P. (1992a) ‘The professionalisation of child care work in Ireland: An unlikely development?’, Children and Society 6(3): 250-66.

O’Connor, T. (2006) ‘Social-care Practice: Bringing Structure and Ideology in from the Cold’ in T. O’Connor and M. Murphy (eds), Social Care in Ireland: Theory, Policy and Practice (pp. 85-100). Cork: Cork Institute of Technology.

O’Connor, T. and Murphy, M. (ed.) (2006) Social Care in Ireland: Theory, Policy and Practice. Cork: Cork Institute of Technology.

O’Gorman, N. and Barnes, J. (1991) Survey of Dublin Juvenile Delinquents, Dublin, St Michael’s Assessment Unit (Finglas).

Ombudsman for Children’s Office (2010) A Report based on an Investigation into the Implementation of Children First: National Guidelines for the Protection and Welfare of Children, Dublin, Ombudsman for Children’s Office.

OMC (Office of the Minister for Children) (2007). Agenda for Children’s Services.

OMCYA (Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs) (2008) National Review of Compliance with Children First: National Guidelines for the Protection and Welfare of Children. Dublin: Stationery Office.

O’Sullivan, D. (1979) ‘Social definition in child care in the Irish Republic: Models of the child and childcare intervention’, Economic and Social Review 10(3): 209-29.

O’Sullivan, E. (2000) ‘A Review of the Children Bill (1999)’, Irish Social Worker, 18 (2-4): 10-13.

O’Sullivan, E. (2009) Residential Child Welfare in Ireland, 1965-2008, Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (Vol. IV). Dublin: Stationery Office.

O’Sullivan, E. and O’Donnell, I. (2007) ‘Coercive confinement in the Republic of Ireland: The waning of a culture of control’, Punishment and Society 9(1): 27-48.

O’Toole, F. (2009) Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption Sank the Celtic Tiger. Dublin: Faber and Faber.

Parton, N. (2001) ‘Risk and Professional Judgment’ in L. A. Cull and J. Roche (eds), The Law and Social Work: Contemporary Issues for Practice (pp. 61-70). Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Raftery, M. and O’Sullivan, E. (1999) Suffer the Little Children: The Inside Story of Ireland’s Industrial Schools. Dublin: New Island.

Richardson, V. (2005) ‘Children and Social Policy’ in S. Quinn, P. Kennedy, A. Matthews and G. Kiely (eds), Contemporary Irish Social Policy (2nd edn) (pp. 171-99). Dublin: University College Dublin Press.

Robins, J. (1980) The Lost Children: A Study of Charity Children in Ireland 1700-1900. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration.

Seymour, M. (2006) ‘Transition and reform: juvenile justice in the Republic of Ireland‘ in J. Junger-Tas and S. H. Decker (eds) International Handbook of Juvenile Justice (pp. 117-43). Amsterdam: Springer Netherlands.

Shannon, G. (2009) Third Report of the Special Rapporteur on Child Protection: A Report Submitted to the Oireachtas. Dublin: Government Publications.

Shannon, G. and Gibbons, N. (2012) Report of the Independent Child Death Review Group. Dublin: Government Publications.

Share, P. (2009) ‘Social Care and the Professional Development Project’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (2nd edn) (pp. 58-73). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Skehill, C. (2003) ‘Social work in the Republic of Ireland: A history of the present’, Journal of Social Work 3(2): 141-59.

Skehill, C. (2004) History of the Present of Child Protection and Welfare Social Work in Ireland. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press.

Smith, J. M. (2001) ‘Remembering Ireland’s “architecture of containment”: Telling stories in The Butcher Boy and States of Fear’, Eire-Ireland: A Journal of Irish Studies 36(3 and 4): 111-30.

Smith, J. M. (2007) Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries and the Nation’s Architecture of Containment. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Smith, R. (2005) ‘Welfare versus justice – again!’ Youth Justice 5 (1): 3-16. Social Service Inspectorate SSI (2001) The Newtown House Inquiry Report. Dublin: SSI.

Spratt, T. (2001) ‘The influence of child protection orientation on child welfare practice’, British Journal of Social Work 31: 933-54.

Stein, M. (2008) ‘Resilience and young people leaving care’, Child Care in Practice 14(1): 35-44.

Streetwise National Coalition (1991) At What Cost? A Research Study on Residential Care for Children and Adolescents in Ireland. Dublin: Focus Point.

Task Force on Child Care Services (1975) Interim Report to the Tanaiste and Minister for Health. Dublin: Stationery Office pp 8-9.

Tuairim-London (1966) Some of Our Children: A Report on the Residential Care of Deprived Children in Ireland. Tuairim Pamphlet 13. London: Tuairim.

Walsh, K. (2013) ‘Children as victims: how sentimentality can advance children’s rights as a cultural concept’, International Family Law, Policy and Practice 20-32.

Webb, S. A. (2006) Social Work in a Risk Society: Social and Political Perspectives. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Whyte, G. (2002) Social Inclusion and the Legal System: Public Interest Law in Ireland. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration.