Chapter 5 – Catherine Carty (D1SOP5)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 5

Respect and uphold the rights, dignity and autonomy of every service user including their role in the diagnostic, therapeutic and social care process.

|

KEY TERMS Human rights-based Approach Respect Rights Dignity Autonomy Participation

|

Social care is … about supporting the children and families we work with to bring about changes in their lives. It is about working with them to identify areas for change, in order that their lives can be the best they can be. As a social care worker, it is not about being their friend or their confidante, it is about being the person they can trust to hear them, to acknowledge their ability to be self-directional in their own lives, to empower them to participate in decisions which affect them and finally to work with them (and others) to find solutions. |

Introduction

Social care workers work in many different settings – with children and young people, families, children and adults with disabilities, adults in homeless or addiction services, in day, residential or community-based support services. Regardless of the sector, or setting, we have a professional responsibilityto respect and uphold the rights, dignity and autonomy of every person we are working with. This is particularly important with regard to involving those we are supporting in their assessment of need and subsequent diagnosis or work plan. It also relates to facilitating the meaningful participation of our clients in the therapeutic interventions we engage in as part of a professional social care process. This Standard of Proficiency dovetails with others in this publication, but specifically Domain 5 Standard 3 (Chapter 64) and Domain 5 Standard 13 (Chapter 74). You might find it useful to read this chapter in conjunction with Chapters 64 and 74. In exploring this Standard of Proficiency, this chapter will draw on the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) 2019 publication Guidance on a Human Rights-based Approach in Health and Social Care Services. Additional support material will be included and will be supplemented by case examples and tasks for practice.

TASK 1

Read the journal article Fitzgerald et al. (2020) ‘Translating a human rights-based approach into health and social care practice’ in the Journal of Social Care, available at https://arrow.tudublin.ie/jsoc/vol3/iss1/

Throughout my career, starting as a social care worker in the 1980s to being employed on the Social Care Programme with Limerick Institute of Technology, I have experienced enormous change in the professional landscape of social care practice. I began working at a time when young people were still cared for in industrial schools, where adults with disabilities were cared for in large, congregated settings, and when there was scant involvement with children and families within their own communities. Giving young people, families and others we worked with a voice in decisions that affected them was the exception rather than the norm. Today, we have moved to a place where the rights and autonomy of those we are supporting is underwritten by legislation and where staff and advocacy organisations facilitate their voice to be at the centre of their care and support. Through increased regulation and the impending registration of the social care profession, this standard of quality practice is now a requirement and, through its delivery, will aim to ensure better outcomes in the lives of those we are working with.

Human Rights-Based Approach

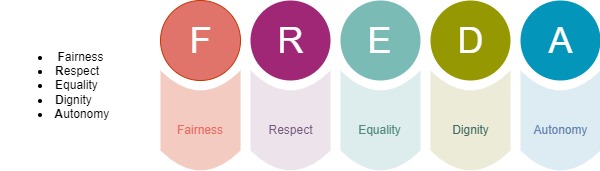

A human rights-based approach is the cornerstone of inclusive practice. ‘Human rights are about people being treated with fairness, respect, equality and dignity; having a say over their lives and participating as fully as possible in decisions about their care and support’ (HIQA 2019: 7). While there has been an increased focus on the importance of working from a rights-based approach, it is perhaps more of a challenge to understand and apply this approach in practice. There are many justifications for practising with an inclusive rights-based approach. First, it supports person-centred care and support, which ensures those receiving services are at the centre of the decision-making process.

Second, it is a professional requirement of the Social Care Workers’ Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics, a code all social care workers will be bound by following registration of the profession (SCWRB 2019). Third, it is enshrined in law. The legal frameworks informing and underpinning policy directives in the state place a responsibility on organisations and individuals to ‘uphold the human rights of people using their services’ (HIQA 2019: 9). A useful framework for exploring how a human rights-based approach can be used in practice is to apply the five FREDA principles (Curtice & Exworthy 2010).

Fairness

Fairness, in the context of a rights-based approach to practice, relates to ensuring that the person receiving the service is at the centre of all decisions made regarding their care and support. Fairness reinforces the core beliefs of equality and autonomy, making sure that the decision-making process is just and free from discrimination. Fairness in our practice can be promoted by providing relevant information. Not everyone can access and understand information relevant to their care and support. Therefore, it is incumbent on us in our practice to provide information that is easily accessible to the people we are supporting. They may need help in understanding the information, the processes or procedures, or the context in which the information is shared. Providing all the relevant information in a way that is accessible to those we are working with will support their ability to provide informed consent to participate in the service we are offering them. People we are supporting have a right to access information about their care and support. To facilitate this, systems should be in place, within services, for service users to access their personal information.

This is particularly the case for those clients who are hard to reach or engage. Examples include, but are not limited to, young people with offending behaviour, people in active addiction, members of ethnic minority communities, etc. We must be creative in how we share information with everyone we are supporting, in a way that is easily accessed and understood. This also goes for gaining their consent to participate in social care processes or exercising their autonomy to not engage. Because someone is hard to reach, or not engaging in support services, this does not negate our responsibility to find ways to fully involve them when decisions are being made about their care and support. All information shared with us should only be used for the purpose it was given, as per current GDPR regulations. In following these regulations, we are obliged to seek permission from those we are supporting, if we are required to share that information with others. People using social care services should never hear from a third party that their information has been shared without their permission.

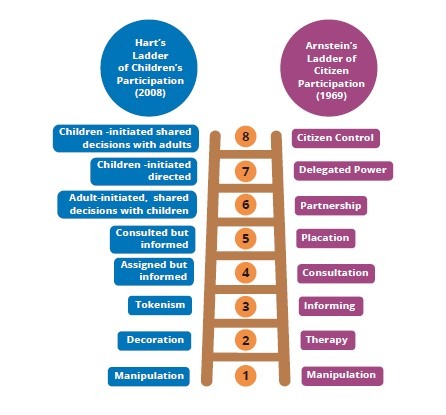

Sherry Arnstein initially devised the ladder of participation in relation to citizen engagement and public participation in the USA. Roger Hart later adapted the ladder to make it applicable to children’s participation and published a seminal text in 1992, which was published by UNICEF. (There is a link to this text in the following practice task.) There are some differences between the two ladders, as you would expect, given that one was aimed at the participation of the general population and the other was aimed at children and young people’s participation. The main differences between the two approaches are: Arnstein identifies steps 1 and 2 as non-participation, while Hart proposes that steps 1-3 are not meaningful participation. Hart’s steps 4-8 refer to different degrees of participation, while Arnstein suggests that his Steps 3-5 are tokenistic involvement with citizen power represented in steps 6-8. The ladder of participation is a useful tool for appraising the levels of service user participation within the organisation you are working in (Arnstein 1969; Hart 1992).

Case Study 1

Where Fairness was practised Liz has an intellectual disability and lived at home with her father until his death. As there were concerns that Liz might not be able to live independently, she was placed in a residential centre. Liz was unhappy in the residential centre and expressed her wish to live independently in the community. Her support team worked with her to put a support plan in place. Liz took part in all discussions about her options and managing risks. She was provided with all the relevant information and training she needed to ensure she understood the choices available to her and could actively participate in the decision-making process regarding her care. After extensive work with Liz, she was supported by staff to move back into the community 12 months later. She now lives independently and receives six hours of support per week. (For other case examples, please see HIQA 2019: 21).

Task 2

To demonstrate fairness in your practice

- Look again at Hart’s ladder of participation. You can read more about the different stages of participation here: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/100-childrens-participation-from-tokenism-to-citizenship.html

- Think about someone you are working with on placement (or in practice).

- Can you identify where the involvement of that person is on the ladder?

- Can you think of a situation where they could be more actively involved in decisions about their care?

- Record what steps you could take to rectify this.

- When completing your practice intervention on placement, consider including an evaluation sheet for your participants, in order to encourage feedback on your piece of work.

Respect

HIQA suggests that ‘respect is shown in the actions towards a person by others and can be demonstrated by communicating in a courteous manner’, which helps those we are working with to ‘feel valued through taking time to get to know them as a person and not as a number or a “condition”’ (HIQA 2019: 25). Showing respect for the people we are supporting is central to providing care and support and is demonstrated in an objective and unbiased way having regard for the person’s rights, values and beliefs. Demonstrating respect for those we are working with can be shown in the way we communicate with them. This begins from the first time we meet them, and continues in introducing ourselves and sharing what our role is in the organisation. In our communication with service users, we respectfully check and re-check their understanding of what is being said, without using jargon or technical language. Cooper says that the social care sector is ‘full of initials, shortenings, technical terms and language that enables professionals to talk about service users and issues quickly and easily’ (2012: 59). However, while we may be familiar with the technical terms or abbreviations, using them with service users when these are not part of their everyday language only serves to alienate them and perhaps make them feel inferior.

Demonstrating respect in practice takes account of the person’s wishes, will and preference for the way they want to live their lives. Gaining knowledge of these entails ‘being present’ while listening to the person we are supporting, and not following our agenda of how we want them to engage with the service. While being mindful of the person’s personal safety and that of others, it is incumbent upon us to support the service user to achieve their personal goals, through the way they want to live their lives, and the relationships they want with those who are important to them.

Where respect was practised

Liam is a new resident in a residential centre for older people, where he has chosen to live. When he meets a new member of staff, they introduce themselves to him. The staff learn about Liam’s background, including his love of painting. When staff speak to Liam, they always address him by his first name, as he has requested. They ask Liam if there is anything else that would help him settle into the centre. Liam asks for photos of his family and for his paintings to be displayed around his room. The staff support Liam in picking out and displaying the photos and paintings he would like to keep in his room. Staff have taken the time to get to know Liam and his preferences and have respected his request for access to his possessions. (For other case examples, please see HIQA 2019).

TASK 3

To demonstrate respect in your practice

- Think about how you greet service users you are working with on placement.

- Do you greet them using their name?

- Do you introduce yourself to them and tell them what your role in the organisation is?

- Do you tell them what will happen when they are in the service?

- Do you offer them refreshments – tea, coffee – when they arrive?

- Think about how you can change the way you greet service users, while being more respectful of them as people.

- Make a list of the steps you could take and try them out when next meeting a service user.

Equality

HIQA describes equality as ‘people having equal opportunities and being treated no less favourably than other people on the grounds set out in legislation’ (HIQA 2019: 32). In the Irish context, these grounds are: age; civil status; disability; family status; gender; membership of the Traveller community; race, colour or nationality; religion; sexual orientation. Therefore, when we ensure we are mindful of equality for all in our practice, we ensure that no one is discriminated against because of their status or characteristics. Some may need additional support to access services in order to achieve the best possible outcomes from the care they receive.

This is achieved through communicating clearly with those we are supporting, in a way that they can understand, regardless of who they are or their communication ability. This may entail adapting our communication style or that of our organisation to be inclusive of everyone. It may mean using different media, besides written material, to provide information to service users. It may also mean adapting policies and other formal material to include graphics and/or making them available in different languages, depending on who may be accessing them.

Being equitable in our practice also means adapting where, when, and how we meet with service users, in order that they are not disadvantaged on the basis of accessibility to, or participation in, services. In doing this, we must be mindful of their ability to make decisions which are right for them, regardless of their age, sexual orientation, race, colour or nationality, status, disability or membership of an ethnic minority. It is our responsibility to remember that discrimination occurs when someone is treated in a different way from someone else in a similar situation, or where people in very different situations are treated the same.

Case Study 3

Case Example: Where equality was not practised

English is not Nadia’s first language, and she often chooses to bring her friend, who speaks fluent English, with her to healthcare appointments to interpret and ensure she does not miss any important details. On one occasion, Nadia had a hospital outpatient appointment. However, her friend was not available to attend the appointment with her. Nadia phoned ahead to ask for an interpreter for the appointment but was told by the clinic secretary that this would not be possible. Nadia felt discriminated against and that no attempt was made to access an interpreter for her. As a result of not having an interpreter, Nadia did not understand everything that was discussed with her and her ability to make an informed decision was compromised. (For other case examples, please see HIQA 2019: 37).

TASK 4

Practice Task: To demonstrate equality in your practice

- Think about how someone whose first language is not English might access your service (or your placement site).

- Unless English is not your first language, this is a difficult task, so try to imagine that Polish is your first language and that you understand very little English.

- When trying this task, go out of the front door of your building and enter it again.

- Look around you to see if you can read anything or see a graphic for anything that makes sense to you. (Remember that you understand very little English.)

- Is there a welcome sign in Polish?

- Are there any graphics that indicate you are welcome in the building?

- Make a list of the pieces of information that you would need to be able to access this service if you were a service user with very little English.

- Try to action some of those thoughts in order to not disadvantage anyone from accessing your service.

- Consider who are the people who use your service.

- Do some have literacy issues?

- If so, perhaps think about working with them to adapt critical policy documents in order to make them more accessible to everyone, including graphics where appropriate. These could then be left in the service for others to use.

- Also think about signs or graphics for the entrance and throughout the building. These could be in different languages, laminated and easy to change as needs be.

Dignity

According to HIQA, dignity means ‘treating people with compassion and in a way that values them as human beings and supports their self-respect, even if their wishes are not known at the time’ (HIQA 2019: 38). Dignity is fundamental to upholding people’s human rights and all human rights are connected to human dignity. When people are treated with dignity and respect, it helps them to trust the people working with them and feel safe. When service users feel safe within a service, the likelihood is that the working relationships can be improved, potentially resulting in better outcomes. When there is a lack of dignity in how we work with those we are supporting, this can result in feelings of insecurity, guilt, shame, worthlessness, anger, frustration, lack of confidence, inadequacy and reduced motivation. These feelings can also be replicated in the staff team. Therefore, showing people dignity in how we work with them is imperative to them feeling valued and respected.

This is achieved through meeting their basic needs of, for example, food, clothing, and personal care. For those who are coming to the service for the first time, this would include showing them where the bathrooms are and where they can get a cup of tea (if possible). When working with people with disabilities, or those who may need assistance with their personal care, it is imperative that this is carried out while always respecting the privacy of the service user. It also means not discussing a service user’s personal history or information within earshot of others, even if those others are colleagues. Private matters should be discussed in private spaces. This requires some planning. When meeting with a service user, make sure a private space is available. When walking to the private space, try to engage in chit-chat rather than beginning the business of the visit, and wait until you are in the private space to discuss private issues.

When speaking with service users, it is crucial that we use the person’s name and gender pronoun when engaging with them, or participating in a meeting with colleagues about them, whether they are present or not. To really demonstrate dignity when working with service users, it is important that we give them the time to share some of their life with us. In fact, it is a privilege if they do. By giving time, we can find out who are the significant relationships in their lives and aspects of their culture or heritage that are important to them. If someone we are supporting is non-verbal, we should work hard to learn from others, including family members, as to their preferences, communicating with them directly, and striving to learn from them what their likes and dislikes are. Through this knowledge, we can adapt the way we support them, so they feel safer, more included and are more able to participate and direct their care.

Case Study 4

Case Example: Where dignity was practised

Fiona is pregnant and has started to experience depression. She has been referred to a midwife with mental health expertise in her local maternity hospital. Fiona does not want others finding out about her depression. The mental health midwife ensures that her privacy is respected at all times. When Fiona is called for her appointment, although the room is a few minutes’ walk from the waiting area, the midwife ensures they are in the consultation room and cannot be overheard before they begin talking. (For other case examples, please see HIQA 2019: 43).

TASK 5

Practice Task: To demonstrate dignity in your practice

- Watch the video in the following link: https://www.scie.org.uk/dignity/care/ videos/choice-control (NOT WORKING)

- Make a note of what you learned from watching the video.

- Think about the service users in the service you are working in, or are on placement in.

- How can you adapt your practice in order to transfer some of your learning from the video to your work with the people you are supporting?

- Prepare some notes from your learning to bring to your next supervision session.

Autonomy

Autonomy refers to ‘the ability of a person to direct how they live on a day-to-day basis according to personal values, beliefs and preferences’; in a health and social care setting, ‘autonomy involves the person using a service making informed decisions about their care, support or treatment’ (HIQA 2019: 46). Cooper advises that ‘clients have a basic right to decide on and consent to their treatment and how to live their life’ and may choose to ‘behave in dangerous, unhealthy or unsafe ways’ (Cooper 2012: 44). This may be a challenging path to navigate for staff and students alike. Therefore, while we can try to use our skills to persuade them to take a different path, we cannot force them to do things they do not want to do. The exception to this is if service users are in danger of hurting themselves or others.

For us to facilitate our service users in demonstrating autonomy in relation to their own care, they may require different levels of support to assert their autonomy and make their own decisions. Key to this is providing, through meaningful communication, all the information they require to make a fully informed decision. It then becomes our duty to accept their decision, whether or not we agree with it, believing that our service users have the right to make a decision that may appear to us to be unwise. If we have provided all the supports necessary to help them make an informed decision about their care and treatment, we then have to take a step back and support their choice, respecting the person ‘as the expert on their own life’ (HIQA 2019: 26).

Case Study 5

Case Example: Where autonomy was facilitated

Jane has a physical disability and had been living in a residential centre. However, she wished to live at home. Following discussion and assessment, her support team in the residential centre felt that this was not ideal, as she was considered to be a person with high needs. Jane and the team discussed this, and she understood and agreed that she would not receive the same level of care at home that she would have in the residential centre. Jane’s wishes were respected, and she was supported to take a measured risk. This was not about discharging Jane from the service, but about supporting her to transition from the residential centre and continuing to provide her with care in a different setting. Staff supported Jane in exercising her autonomy by understanding and respecting her will and preferences and supporting her to live independently. Staff communicate with Jane on a regular basis to make sure that her new living situation is working well for her and identify any additional supports that she may need. (For other case examples, please see HIQA 2019: 52).

TASK 6

Practice Task: To facilitate autonomy in your practice

Think of a situation in practice, where your view would be different from your service user’s, in relation to their best interests. Consider what are the risks and benefits for the service users if their wishes are supported. Think about whether there are risks for the organisation if the service user is supported with their decision. Weigh up the risk and benefits to the service users. In supervision, explore this dilemma with your supervisor (practice educator) to see how best the service user could have their needs met through being supported with their decision.

Summary

This proficiency explores how you respect and uphold the rights, dignity and autonomy of every service user, including their role in the diagnostic, therapeutic and social care process. This can be achieved through keeping those we are supporting at the centre of their care, while providing them with all the information required to help them make decisions in relation to their care and treatment. This should be done with respect, dignity and acknowledgement that individual people are best placed to make these decisions about their lives.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

Throughout this chapter there are tasks and activities to help students engage with this proficiency. Ask students to relate the tasks to your service

![]() Tips for Social Care Educators

Tips for Social Care Educators

To support your teaching and discussion of this Standard of Proficiency with your students, perhaps review HIQA’s dedicated online resource (HIQA 2019), where you will find an academic slide deck that you can download and use with your students. The guidance document that was used as the framework for this chapter is included there and contains additional exercises and reflections for students to engage in. You can also find a link to a human rights-based approach training programme, delivered by HSELanD, which your students might find helpful. The link to the training is available at HIQA (2019).

References

Arnstein, S. R. (1969) ‘A ladder of citizen participation’, Journal of the American Planning Association 35(4): 216-24.

Cooper, F. (2012) Professional Boundaries in Social Work and Social Care: A Practical Guide to Understanding, Maintaining and Managing Your Professional Boundaries. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Curtice, M. and Exworthy, T. (2018) ‘FREDA: A human rights-based approach to healthcare’, Psychiatrist 34: 150-156. Available at <https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-psychiatrist/article/freda-a- human-rightsbased-approach-to-healthcare/0459124A5DF648BE941396FC4F61E1D6>

Fitzgerald, S., Behan, L., McCarthy, S., Weir, L., O’Rourke, N. and Flynn, R. (2020) ‘Translating a human rights-based approach into health and social care practice’, Journal of Social Care 3(3). Available at <https://arrow.tudublin.ie/jsoc/vol3/iss1/>.

Hart, R. A. (1992) ‘Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship’, Innocenti Essays, No. 4. Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Centre. Available at <https://www.unicef-irc.org/ publications/100-childrens-participation-from-tokenism-to-citizenship.html>.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2019) Guidance on a Human Rights-based Approach in Health and Social Care Services. Dublin: HIQA. Available at <https://www.hiqa.ie/reports-and- publications/guide/guidance-human-rights-based-approach-health-and-social-care-services>.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2019) Social Care Workers Registration Board code of professional conduct and ethics. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at https://coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for- social-care-workers.pdf.