Chapter 12 – Maria Ronan (D1SOP12)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 12

Understand and be able to apply the limits of the concept of confidentiality particularly in relation to child protection, vulnerable adults and elder abuse

|

KEY TERMS Confidentiality Child protection Vulnerable adult Elder abuse Life story work Limits of confidentiality Everyday activities |

Social care is … a privilege. It gives us an opportunity to share in someone’s life journey. When a person has vulnerabilities and we have a chance to make their life better in some way, for example making an effort to converse with a non-verbal person, being there consistently for someone on their long winding road through rehab or ensuring that an older person knows that their life continues to have value, we ourselves will be rewarded with an increase in our feelings of self-worth. Social care also means fun and enjoyment – there can be laughter with the people we support, even in the most challenging situations. |

Confidentiality: Definition

TASK 1

Describe a time when you told someone something important that you asked them to keep private and later found out that they had told others. How did this experience make you feel – about the other person, but also about yourself, for instance, your ability to make judgements?

Understanding Confidentiality

Going through life, we all have experiences we would prefer that no one else knows about. These experiences can result from a range of factors including biological, environmental, social, financial, health, substance misuse, to name but a few. However, when a person enters the care system – which can occur at any stage in the life cycle – files are opened and records are updated on a continuous, probably daily, basis. The range of information that social care workers are obliged to document is comprehensive: monitoring health issues and all medication that has been administered; instances of challenging behaviour; contact with family members and others known to the person; the person’s ability or otherwise in relation to their own personal care; foodstuffs they like and dislike; all social outings. Indeed, every possible aspect of the person’s life may be recorded.

Among the reasons for this are to ensure that the various staff coming on duty are kept apprised of the person’s needs and are also aware of the person’s impact on others using the service, particularly in relation to verbal and physical behavioural issues. However, for anyone to know that their personal business is documented, in either hard copy format, on a computer or both, could, at a minimum, make them feel uncomfortable.

TASK 2

Think of a time when you made a mistake, when you did something that you regretted, something that you hope other people have now forgotten all about. Try to imagine this incident being documented in detail and placed in a file. Consider how you might feel if you knew that many different people, over a long period of time, would read over this and would know all about what had happened. What emotions could come up for you?

Understanding Confidentiality from the Other Person’s Perspective

When working in a social care setting, you may be asked to sign a statement of confidentiality, but even if you are not, you have an ethical and moral obligation to respect people’s right to privacy. Furthermore, there are statutory obligations on social care workers to comply with confidentiality guidelines. The Social Care Workers Registration Board Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics details the obligations on social care workers in relation to respecting the privacy and confidentiality of service users (SCWRB 2019: 9-10). To read about the key data protection legislative frameworks applicable from 25 May 2018 resulting from the General Data Protection Regulations, go to the Data Protection Commission’s website: www.dataprotection.ie.

In social care work, there are many cohorts of people with different types of vulnerability and support needs, and even within particular cohorts, some people will need greater levels of support than others; areas of concern include child protection, vulnerable adults and elder abuse. Indeed, all children and vulnerable adults, as well as older people, can be at risk of abuse. The Health Service Executive (HSE) sets out the definition of abuse, the types of abuse, who can perpetrate abuse and where abuse may occur, in its guidelines on safeguarding vulnerable people at risk of abuse (HSE 2014: 8-10). This document also provides clear information on topics including recognising abuse, safeguarding and the roles and responsibilities of staff at different levels.

Importantly, this publication states that ‘All vulnerable persons must be secure in the knowledge that all information about them is managed appropriately and that there is a clear understanding of confidentiality among all service personnel’; that concerns or allegations are shared among staff ‘on a “need to know” basis in the interest of the vulnerable person’ and that ‘No undertakings regarding secrecy can be given’ (HSE 2014: 7-9). This section of the Safeguarding Policy and Procedures document, indeed the entire document, will be hugely beneficial to all those entering or currently working in social care.

Areas of social care where we may be privy to confidential information:

Social care workers learn the details of people’s lives in various ways. A certain amount of knowledge of someone’s personal information is necessary in order be able to help them, either in a crisis situation or to plan long term for optimum care. Other times we work creatively with a person by listening to their accounts of their past experiences, to help them understand their situation or simply to validate their lives. An example of this is life story work.

Life Story Work and Good Confidentiality Practice

Life story work is an intervention that can help children who have experienced bereavement or who are not living with their biological parents, such as children in residential or foster care, or adopted children. The Irish Foster Care Association (IFCA) states that the goal of life story work in working with children is to create a safe space in which a child can explore their past, present and future.

The information gleaned from any life story work should be treated in confidence, in the same way as information obtained in other ways such as from multidisciplinary team members (doctors, psychologists, social workers, speech and language therapists, nurses, psychiatrists, etc.). It is imperative to be aware that families, friends, carers and other professionals do not have an automatic right to data about a service user; consent should always be obtained prior to discussions with anyone other than your immediate colleagues. Even after the death of a service user, their privacy should be respected. If there is any uncertainty around what to disclose or to whom, your manager will provide guidance based on policies, legislation and their own professional experience.

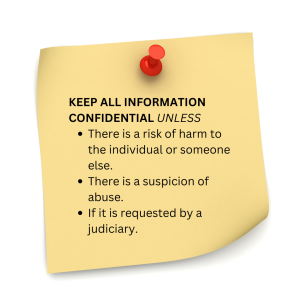

Limits to Confidentiality

It is important never to give a supported person an assurance of confidentiality as information may come to light when undertaking life story work – particularly for children in foster/residential care – which would need to be passed on to the relevant authorities.

National guidelines on reporting allegations of or suspected abuse have been introduced, with many sectors also having their own guidelines (Lalor et al. 2007: 292-3). CORU states that concerns must be reported to the appropriate person or authority in order to ‘prevent harm to the service user or a third party; to prevent harm to the public at large, [or] to comply with a legal requirement’ (SCWRB 2019: 9).

In many sectors such as residential childcare, social care workers have to deal with quite upsetting and difficult issues when they learn of trauma experienced by some children and young people. Having to tell a person who confided in you that you have a duty to notify an authority figure can be a challenge when you want children who are out of home and have had a range of different adults in their lives to trust you. Nonetheless, if you have any concerns at all, always inform an appropriate person (such as your manager) or authority (for example An Garda Síochána).

CORU’s guidance to the person making a report is to ‘inform the service user of the disclosure unless this would cause them serious harm or put the health, safety or welfare of a third party at risk’ (SCWRB 2019: 10). Such a situation could be distressing for the student or social care worker: not only have they learned of a difficult issue but the person in their care may feel let down. This is why it is vital that no promise of confidentiality is ever made. Although the priority is to support the person who has made a disclosure, appropriate professional supervision should be mandatory for the student or staff.

CORU’s guidance to the person making a report is to ‘inform the service user of the disclosure unless this would cause them serious harm or put the health, safety or welfare of a third party at risk’ (SCWRB 2019: 10). Such a situation could be distressing for the student or social care worker: not only have they learned of a difficult issue but the person in their care may feel let down. This is why it is vital that no promise of confidentiality is ever made. Although the priority is to support the person who has made a disclosure, appropriate professional supervision should be mandatory for the student or staff.

To guide students in reflecting on challenges around confidentiality and trust in social are, McCann James et al. (2009: 113-25) offer a fictional scenario in a residential centre for children and young people. Questions are provided for students to consider when attempting to navigate their way through the ethical considerations they may face. Sociological, psychological and professional perspectives are presented.

Confidentiality is also a key consideration in life story work with older people and those with dementia. Pouchly et al. (2013: 116) describe life story work as ‘biographical approaches used with individuals with communication or memory difficulties within health and social care’, suggesting the central role that recording memories and gathering items such as photographs can have in helping to sustain a person’s identity and treasure their memories. An example of a life story book template can be found in the appendix to this article (Pouchly et al. 2013: 125-6).

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

In order to meet this proficiency, it is vital for the student to understand the importance of confidentiality. One of the priority tasks of a practice educator when students commence their placement is to explain the necessity of confidentiality and to ask students to sign a statement of confidentiality (this document may in any case be an essential component of students’ practice placement portfolios). Throughout a placement, students should be afforded regular opportunities to read national and internal policy documents relating to confidentiality, and to ask questions, as some of the terminology may be unfamiliar to them. As different matters arise, educators can remind students of the importance of not discussing what happened with anyone outside the immediate service. This will demonstrate on an ongoing, practical basis how reading around confidentiality relates to real-life situations, giving students an insight into applying theory to practice.

Each work placement agency will differ regarding how much access students are given to service users’ files, and clear guidance must be provided. If a student is required by their college to complete a case study on a service user, they should be assisted to identify a service user who either has the capacity to consent to being the subject of a case study or whose next of kin will be happy to give consent. However, even if the case study is sanctioned, the person’s identity should always be anonymised. While the responsibility to do so will have been explained to students in college it should be re-emphasised by placement staff and the student’s supervisor should read the portfolio to ensure that identifying details have not been inadvertently included.

Students might not be aware that even family members are not automatically entitled to information. It may be that only the certain people such as named family members, or someone who has been granted (enduring) power of attorney, can be notified of matters pertaining to a service user. In particular, if a student will be answering the work telephone, they will need to know with whom they may discuss issues, even of a non-sensitive nature. Furthermore, a student may wrongly believe that any person working in the organisation, or other professionals such as those on a multi-disciplinary team involved in the care of those supported by the placement agency, have a right to access data. The placement supervisor should apprise students of legislation, codes of confidentiality, best practice in this area and the internal policies of the agency, and monitor their understanding.

Crucially, students need to be informed of the legal and ethical dimensions regarding the limits of the concept of confidentiality. Staff can discuss with students situations where disclosure of confidential information to the appropriate authority is an ethical and/or legal necessity: these include where there is a risk of harm to the service user or others, where abuse is suspected, or to comply with a legal requirement. Tusla’s guidelines on the Children First Act 2015 and the HSE’s Safeguarding Vulnerable Persons at Risk of Abuse provide comprehensive guidance on this aspect of safeguarding (Tusla website; HSE 2014).

References

Government of Ireland (2015) Children First Act 2015. Dublin: Stationery Office. Available at: <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2015/act/36/enacted/en/pdf>

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2012) Guidance on Information Governance for Health and Social Care Services in Ireland: Safer Better Care. Dublin: HIQA. Available at: <https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2017-01/Guidance-on-information-governance.pdf>.

HSE (Health Service Executive) (2014) Safeguarding Vulnerable Persons at Risk of Abuse National Policy and Procedures: Incorporating Services for Elder Abuse and for Persons with a Disability. Dublin: HSE. Available at: <https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/corporate/personsatriskofabuse.pdf>.

HSE (2021) GDPR Information (online), available at: https://www.hse.ie/eng/gdpr/ [accessed 8th September, 2021}

Lalor, K., de Róiste, Á. and Devlin, M. (2007) Young People in Contemporary Ireland. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

McCann James, C., de Róiste, Á. and McHugh, J. (2009) Social Care Practice in Ireland: An integrated perspective. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Pouchly, C. A., Corbett, L. H. and Edwards, K. (2013) ‘Life story work: Overcoming issues of consent and confidentiality’, Quality and Aging in Older Adults 14(22): 116-27 <https://www.emerald.com/insight/ content/doi/10.1108/14717791311327060/full/html>.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2019) Social Care Workers Registration Board code of professional conduct and ethics. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at https://coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for- social-care-workers.pdf

Tusla (Child and Family Agency) (website) ‘Mandated Persons’ <https://www.tusla.ie/children-first/ mandated-persons/> [accessed 10 November 2020].