Chapter 14 – Teresa Brown and Margaret Fingleton (D1SOP14)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 14

Be able to recognise and manage the potential conflict that can arise between confidentiality and whistleblowing.

|

KEY TERMS Whistleblowing Understanding social care Confidentiality Whistleblowing Legislative framework

|

Social care is … based on building relationships and making connections by drawing on the personal, academic and professional self. |

TASK 1

Think of a time when you were asked to keep a secret, but it didn’t feel right.

Understanding Social Care Work

Social care has been a great companion in our life journey. It has equipped us to manage in difficult times, reminded us of our good fortunes, grounded us in reality and opened many doors to opportunities that we might have otherwise overlooked. Drawing on the personal, academic and professional self is key to social care practice, and this requires the integration of knowledge of self, ongoing development of skills and competencies and the ability to be present for those around us. Building relationships and connections has been the cornerstone of our social care experiences and working with others has shaped not only our practice but our perspective on life itself.

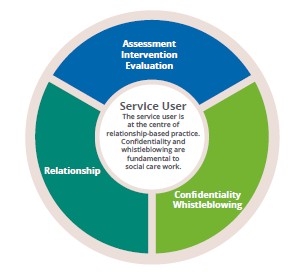

Social care has been defined and redefined over the years, but recently CORU (SCWRB 2019) has offered a broad definition that will finally take social care practice into the professional realm. Social care practice is constantly changing and evolving to respond to societal care needs and demands. The individual is at the centre of the work and social care workers ‘engage in assessment, intervention and evaluation in a way that is bespoke, co-produced, fluid and organic’ (McGarr & Fingleton 2020). These processes are the bedrock of purposeful planning and service provision; however, despite the adaptions of defining social care, relationship have always been at the core of social care practice. Fundamental to this relationship-based approach is confidentiality and allied to this is the facility to engage in the whistleblowing process, now enshrined in Irish legislation.

Confidentiality

TASK 2

Read the Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics (SCWRB 2019) and find all the references to confidentiality and whistleblowing.

Confidentiality is a central feature of the relationship between the social care worker and the service user. The concept of confidentiality occupies a central position in social care educational programmes and is consistently referenced in legislation (Data Protection Act 2018) and policy (HIQA 2018; SCWRB 2019). However, despite our ethical and legal duty to respect confidentiality, we recognise that confidentiality cannot be absolute; there are many exceptions to client confidentiality, exceptions that are related to welfare and protection guidelines. More recently, social care workers are encountering ethical issues relating to confidentiality; computerised systems mean that social care workers have had to incorporate the use of technology into practice and must be cognisant of their impact on confidentiality and whistleblowing. The often-overlooked ethical issue in social care literature is the complexity of confidentiality when applied to whistleblowing events. Integral to our discussion on proficiency 1.14 (‘Be able to recognise and manage the potential conflict that can arise between confidentiality and whistleblowing’) is our view that challenging unethical practice and reporting concerns is a key element of social care workers’ practice. There is clear guidance in our Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics on managing the potential conflict that can arise between confidentiality and whistleblowing, outlining the expected standards of behaviour and response.

Social care history gives us an insight into an organisational and societal culture that was not conducive to whistleblowing. The Ryan Report (2019) highlighted how witnesses stated that there was an awareness that children were being abused. The report stated that local people who were employed in residential centres as professional and ancillary staff and who tried to highlight the abuse were punished, and pressure was brought to bear on the child and family to deny complaints made. However, the social care landscape has changed and there is now an understanding that those who whistleblow are striving to improve service provision and delivery. The framework of support is articulated in Tusla’s guidelines, which state that Tusla is committed ‘to addressing concerns and supporting workers in speaking-up relating to potential wrongdoing in the workplace and to providing the necessary support for workers who raise genuine concerns (Tusla 2017: 7).

What is Whistleblowing?

The term whistleblowing originated from British police officers blowing their whistles to warn the public of a crime in progress. In addition, private business owners would use their own whistles to alert police that a crime was being committed. Current understanding of whistleblowing is the disclosure by a person working within an organisation of acts, omissions, practices or policies by persons within the organisation that are considered wrong or harmful to a third party. Reporting and/or highlighting these perceived practices has become known as whistleblowing (Tusla 2016). There have been highly publicised examples of whistleblowing in the media, particularly the account of whistleblower Garda Maurice McCabe. McCabe’s disclosures of practices in An Garda Síochána led to some significant reforms in the force and to some major political debates, which resulted in a Tribunal (established in 2017), which examined whether there had been a smear campaign against him by the force. The case focused on the treatment of McCabe, who was falsely accused of child sexual abuse after he raised concerns about Garda malpractice. He settled his actions against An Garda Síochána and Tusla over the processing of a false allegation against him. This case demonstrated the complexities of whistleblowing, highlighting in particular the level of stigma attached to the act of whistleblowing. Arguably, however, there has been an attitudinal shift from ‘snitch’ to a more respectful orientation of acting responsibly and this is evident in the legislative framework.

Legislative Framework

The Protected Disclosures Act 2014 aims to protect workers from reprisal where they voluntarily disclose information relating to wrongdoing in the workplace that has come to their attention. The term ‘worker’ is defined broadly and includes employees, contractors, the self-employed, agency workers and people on work experience and placement. All public bodies are now required to have whistleblowing procedures in place to deal with disclosures under the 2014 Act by workers who are employed by them and to provide details of these procedures to their workers. The Tusla policy entitled Protected Disclosures Policy and Procedure: A Guide for Whistleblowing on Alleged Wrongdoing encourages workers to raise concerns about serious wrongdoing within their workplace rather than ignoring a problem or reporting it externally. The document states that Tusla is ‘committed to maintaining the highest standards of honesty, openness and accountability and actively encourages those with knowledge of wrongdoing to come forward’ (Tusla 2016: 5).

There are penalties for any employers or other persons who punish or intimidate persons for whistleblowing, through various legislative frameworks. The Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 and Employment Permits Act 2006 offer protection to whistleblowers; and the Protections for Persons Reporting Child Abuse Act 1998 provides protection for people reporting suspected child abuse in good faith. Despite legislative protection, issues can emerge with the potential conflict that can occur between confidentiality and whistleblowing.

Confidentiality and Whistleblowing

As social care workers we are aware of the limits of confidentiality when we have a duty to disclose information, but this is different from whistleblowing.

|

DUTY TO DISCLOSE |

WHISTLEBLOWING |

|

Obligation |

Protection |

|

Involuntary |

Voluntary |

Balancing the obligation to highlight concerns against our duty to maintain confidentiality is a challenging ethical issue faced by social care workers. When considering whistleblowing, one could argue that if the issue is about a particular person or individual case, one can see the argument for confidentiality. Conversely, if it is about organisational practices, the need for confidentiality and the enforcement of confidentiality can cause particular challenges. These challenges are centred on enforced silence and secrecy. Confidentiality can be revealed as problematic and may be viewed as a means to silence and isolate.

The SCWRB Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics (2019) puts the safety of service users ahead of personal and professional loyalties. The code can guide and support our practice and help us manage the conflict that can arise between confidentiality and whistleblowing. Section 2 of the code refers to respecting the confidentiality and privacy of service users.

|

You Must |

You Should |

|

a. Keep service user information securely and, subject to other provisions of this code, treat it confidentially, including guarding it against accidental exposure. |

a. Continue to treat service user information as confidential even after the death of the service user. |

|

b. Share service user information with others only where and to the extent necessary to give safe and effective care or where disclosure is mandated by law. |

b. Be aware of the following circumstances in which disclosure of confidential information in the absence of consent may be appropriate, justifiable and/or required by law: to prevent harm to the service user or a third party, to prevent harm to the public at large, to comply with a legal requirement. |

|

c. Inform service users of the limits of confidentiality and the circumstances in which their information may be shared with others. |

|

|

d. Obtain the consent of a service user before discussing confidential information with their family, carers, friends, or other professionals involved in his/her care. |

c. Inform the service user of the disclosure unless this would cause them serious harm or put the health, safety or welfare of a third party at risk. |

|

e. Always follow employer guidelines and relevant legislation when handling service user information |

d. Where you decide that disclosure is justified, you should ensure that the disclosure is made to an appropriate person or an organisation, and that the extent of the disclosure is minimized to relevant information (SCWRB 2019: 9). |

|

f. Always follow best practice in relation to the use of service user information in clinical audit, quality assurance, education, training and research. |

|

SCWRB Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics (2019: 9)

Case Study 1

Maura has been working for a number of years as a social care worker in a residential unit. She enjoys her work and has a very positive relationship with service users and colleagues. In recent weeks one of the service users told Maura that Jane, the unit manager, had borrowed money from her. The service user did not want to make a complaint but was very worried about Jane. When Maura spoke to Jane about this, she noted a smell of alcohol on Jane’s breath. Jane was upset when confronted about borrowing money and confided in Maura that she was going through a difficult time. The following week, when balancing the weekly budget, Maura noticed that money was missing. Maura was very upset over the incidents and unsure what to do next. She is fearful about reporting her concerns as Jane is a very popular manager and well-respected by senior management.

This case study demonstrates that one of the most difficult aspects of whistleblowing is unethical practices of a colleague; unethical practices that you think may be overlooked or even supported by management or the organisation. It can be difficult to report these incidents, and the following statements can be justifications that you may use to avoid being a whistleblower.

- The manager has given her life to the job over the years, so she probably deserves the money she is taking.

- It might just be a loan that she will pay back.

- Misappropriating resources for personal use is no big deal – lots of people do it.

- If it’s my word against the other staff member, nobody will believe me.

- The service user does not want to cause trouble; she confided in me.

- The service users would be annoyed with me; they talk about loyalty and consider people who inform to management as ‘rats’.

- I don’t have the energy to pursue this matter.

- Speaking about our unit may give the team a bad name.

- I am breaking service user trust and confidentiality.

- Social care is a small world; people will think badly of me because Jane is very popular.

These statements provide an insight into the complexities of managing the potential conflict that can arise between confidentiality and whistleblowing. It is therefore important to consider our responsibility as social care workers: in our daily practice we encourage and support services users to use their voice in highlighting injustice; we too must use ours. Arguably, whistleblowing in social care work could be viewed as a type of advocacy, as it can highlight unethical behaviours or practices on behalf of service users. Social care workers who perceive or witness poor practice and face the dilemma of whether or not to act need to access emotional support and professional supervision. Greater attention needs to be given to the support that is available for those who are involved in whistleblowing. Seeking out support is important; supervision team members or other professional colleagues may all play a role in this support matrix. The media reports of whistleblowers’ experiences describe limited supports and some negativity from colleagues towards those who highlighted issues, so it is vital to be able to identify those who may be able to offer support, advice and structures to follow the correct procedures.

External supervision may not be available, but it may be a resource your agency could consider providing if requested. External supervision can offer a confidential and safe space for workers to discuss whistleblowing events. If external supervision is not available, it is important that there is one identified person within the organisation with whom whistleblowers can discuss the issue and gain support.

TASK 3

The HSE’s national ‘Your Service Your Say’ office comes under the remit of the National Complaints Governance and Learning Team (NCGLT) within Quality Assurance and Verification (QAV). (See www.hse.ie/eng/about/qavd/complaints/ ysysguidance/appendices/ysysleaflet/ysys-feedback-leaflet.html. not working)Your Service Your Say ensures the fundamental right for people to voice opinions, provide comments and make a complaint, with a focus on creating a positive environment and culture to encourage and learn from feedback, especially complaints. Create an easy-to-read poster/flyer for a range of service users explaining how to access this service and how to make a complaint. https://www2.hse.ie/complaints-feedback/

Organisational Response

How do we create cultures where we can manage the potential conflict between confidentiality and whistleblowing? Organisational policies may require confidentiality to be enacted to protect whistleblowers in relation to due process if an investigation is under way. When professionals are following policy regarding confidentiality, this can be isolating and enforced silence can create a culture where rumours and gossip can exist. However, it is important to note that if there is a conflict between your agency policy and the SCWRB Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics, your professional and legal obligation is to this Code (2019: 23).

The importance of creating cultures that are open to complaints was identified in the Office of the Ombudsman’s Learning to Get Better report (2015). This report looked at how hospitals handle complaints and found that people do not complain because of the feared negative repercussions, and they believe that complaining will not make a difference. The report recommended the need to create cultures that welcome complaints and highlighted the importance of acting on lessons learned. The open disclosures policy (HSE 2019), which has been adopted by several social care organisations, promotes the following:

- Full knowledge about the person’s care and treatment is facilitated

- Clients are informed when things go wrong

- Meetings will be organised to discuss what happened

- A sincere apology can be made if there was an error while caring for the person

- Clients will be treated with compassion and empathy (HSE 2019).

If management structures are not open to complaints or to staff highlighting issues, professionals may report outside their organisations, so we need to ensure that internal avenues for reporting are accessible, clear and supportive. The importance of organisations having a whistleblowing policy in place cannot be overstated, and the existence of a whistleblowing policy demonstrates an agency’s openness and transparency to areas of concern. By having clear policies and procedures for dealing with whistleblowing, an organisation shows that it is open to information being brought to the attention of management. It is only when social care workers feel safe and supported in their organisations that they will be confident about exposing concerning practices and managing the potential conflict between confidentiality and whistleblowing.

Arguably, if we construct and view whistleblowing as a positive and proactive action, it may lead to important information about risks or poor practice being brought to our attention. Social care workers at the frontline are often best placed to identify deficiencies and practices before things reach crisis point, so the importance of social care worker role as the watchdogs of organisations is central.

TASK 4

Watch the YouTube video on Whistleblowing in Social Care: Improving Organisational Practice: www.youtube.com/watch?v=oKtGgH7-eR0. In small groups, reflect on how this learning relates to placement experiences.

Tips for Practice Educators

Social care programmes will have covered whistleblowing in terms of definitions and policies; however, students would benefit from ethical scenarios that allow them to reflect on the following from the SCWRB Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics.

- Put the safety of service users ahead of personal and professional loyalties (p. 9).

- Insofar as possible, protect service users if you believe they are or may be at risk from another professional’s conduct, performance, or health (p.8).

- If you become aware of any situation that puts a service user at risk, bring this to the attention of a responsible person or authority (p.8).

How do students raise concerns about safety and quality of care?

A. Inform an appropriate person or authority if you are aware of systems or service structures that lead to unsafe practices which put service users, yourself, or others at risk.

B. Raise the issue outside of the organisation if your concerns are not resolved despite reporting them to an appropriate person or authority.

C. Act to prevent any immediate risk to a service user by notifying the relevant authorities of any concerns you have about service user safety as soon as possible.

It is important that students are informed about the policies and processes for whistleblowing and that they are given support and direction if they need to challenge unsafe behaviours and cultures and organisational wrongdoing. Students need to be reassured that they can disclose openly and safely without fear of adverse consequences. Some students may find it difficult to challenge unsafe behaviours and organisational wrongdoing for fear of failing a placement or impacting future employment opportunities.

Practice educators and placement supervisors should be cognisant of this and be aware of the need to support students to take appropriate action if necessary. Course provider and placement provider policies should set out the processes and the support students can expect to receive from their colleges if they raise concerns or whistleblow.

Finally, the SCWRB (2019:20) outlines clearly what steps students should take when they have concerns:

Suggested procedure for decision-making

a. Identify the problem and gather as much information as you can. Ask yourself if it is an ethical, professional, clinical or legal problem.

b. Review the Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics and identify the relevant parts. Check other professional guidelines too, such as those of the HSE or government departments, as well as any relevant legislation.

c. Discuss the issue with professional colleagues, being mindful of your obligation to respect the confidentiality of the service user.

d. Consider asking your professional body for advice.

e. Evaluate the rights, responsibilities and welfare of everyone affected. Remember that your first obligation is to the service user

f. Keep notes at each stage of the process. Consider different solutions and decisions.

g. Evaluate and document the potential consequences of each option.

h. Choose the best solution or decision based on your professional judgement.

i. If you have any concerns about the legality of your chosen course of action, seek professional advice at the earliest opportunity.

k. Put the solution or decision into practice, informing all the people affected.

l. Remember that you are accountable, as an autonomous practitioner, for the consequences of the solution or decision that you choose.

References

CORU (2020) Update on the Registration of Social Care Workers. Available at <https://coru.ie/about-us/ registration-boards/social-care-workers-registration-board/updates-on-the-social-care-workers- registration-board/update-on-the-registration-of-social-care-workers/>.

Data Protection Act (2018). Dublin; Stationery Office. Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/ eli/2018/act/7/enacted/en/html>.

Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth (2019) Report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (Ryan Report). Available at <https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/3c76d0-the- report-of-the-commission-to-inquire-into-child-abuse-the-ryan-re/>.

Employment Permits Act (2006). Dublin: Stationery Office. Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/ eli/2006/act/16/enacted/en/html>.

General Data Protection Guidelines (GDPR) (2017), Relate 44(8):1.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2018) Guidance Document for Protected Disclosures. Available at <https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2020-07/guidance-protected-disclosures.pdf>.

HSE (Health Service Executive) (2018) Open Disclosures Policy. Available at <https://www.hse.ie/eng/ about/who/qid/other-quality-improvement-programmes/opendisclosure/hse-open-disclosure-full- policy-2019.pdf>.

McGarr, J. and Fingleton, M. (2020) ‘Reframing social care within the context of professional regulation: Towards an integrative framework for practice teaching within social care education’, Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies 20(2): 5. Available at <https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijass/vol20/iss2/5>.

Ombudsman, Office of the (2015) Learning to get Better Report. Available at <https://www.ombudsman. ie/publications/reports/learning-to-get-better/Learning-to-Get-Better-Summary.pdf>.

Protected Disclosures Act (2014). Dublin: Stationery Office. Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook. ie/eli/2014/act/14/enacted/en/html>.

Protection for Persons Reporting Child Abuse Act (1998). Dublin: Stationery Office. Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1998/act/49/enacted/en/html>.

Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act (2005). Dublin: Stationery Office. Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2005/act/10/enacted/en/print>.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2019) Social Care Workers Registration Board code of professional conduct and ethics. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at https://coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for- social-care-workers.pdf

Tusla (Child and Family Agency) (2016) Protected Disclosures Policy and Procedure: A Guide for Whistleblowing on Alleged Wrongdoing. Dublin:Tusla. Available at <https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/ Tusla_Protective_Disclosure_Policy.pdf>.

Tusla (2017) Child Protection and Welfare Strategy 2017-2022. Dublin: Tusla. Available at <https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/Tusla_Child_Protection_and_Welfare_Strategy.pdf>.

Workplace Relations Commission (2014) Code of Practice on Protected Disclosures Act 2014 (Declaration Order). Available at <https://www.workplacerelations.ie/en/what_you_should_know/ codes_practice/cop12/>.