Chapter 1 – Denise Lyons (D1SOP1)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 1

Be able to practise safely and effectively within the legal, ethical and practice boundaries of the profession.

|

KEY TERMS Practice boundaries of the profession Legal, ethical and practice boundaries Zone of helpfulness Shared duty to care Professionalisation

|

Social care is … a profession that requires an in-depth understanding of and interest in people. Practice is centred within the relationship between you and another person. Social care work places an onus on the worker to constantly reflect on her/his attitudes, physical and mental health and ongoing ability to focus on and be present with the service user(s). The work is emotionally and physically challenging because you use your self as the ‘tool’ (Lyons 2013). |

Practice Boundaries of the Profession

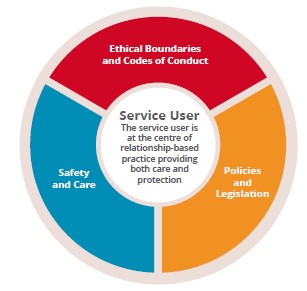

The practice boundaries of social care support workers to provide safe, ethical and legal practice.

Professional boundaries are a set of guidelines, expectations and rules which set the ethical and technical standards in the social care environment. They set limits for safe, acceptable and effective behaviour by workers (Cooper 2012: 11). Professional boundaries are one of the defining characteristics that separates unskilled labour from a profession (Eraut 1994). According to Hashimoto (2006), the word ‘profession’ means to profess or declare that, as a professional, you will fulfil your duty in society, using expert knowledge, and are regulated, autonomous and accountable. A key characteristic of any professional body is its ability to make independent decisions about, and to have self-governance on, the definition, role, scope and duties of its members. Autonomy is derived from a Greek word meaning self-governance, and on a personal level, it relates to the ability to be in control of and make decisions about your own life (Rendtorff 2008). Professional autonomy relates to the ability to make decisions and judgements within the work environment, which are not absolute, but shaped and limited by guidelines or codes of ethics established by the profession (Hashimoto 2006). The eighty standards of proficiency, presented as individual chapters in this book, outline all the skills and knowledge needed to practise safely and effectively within the boundaries of our profession. These standards of proficiency are supported by a Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics and ‘each year registrants will be asked to pledge that they comply’ (SCWRB 2019: 1). The 27 ‘responsibilities’ in the Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics (2019) are categorised under three subheadings; Conduct, Performance and Ethics. Chapter 7 provides an overview of this document and looks specifically at the codes of conduct that are not already included in the eighty standards of proficiency. Accountability is being able to explain the decisions or actions you have made, or not taken, to the people who are directly affected by them (De Lissovoy 2013). Accountability is an important part of professionalisation and when people can stand over their decisions, practice becomes more transparent and safe. Regulation is about accountability to the service user, requiring discipline and adherence to the codes of ethics and conduct, and being answerable for our actions through a sense of individual responsibility. Regulation and accountability are part of a quality assurance process, which begins by setting standards, providing training and then implementing the standards and codes of conduct. This is a cyclical process and ‘as the profession develops, the Social Care Workers Registration Board is committed to continually reviewing these standards, in doing so, ensuring that they remain both relevant and comprehensive’ (SCWRB 2019: 2).

Professional boundaries are a set of guidelines, expectations and rules which set the ethical and technical standards in the social care environment. They set limits for safe, acceptable and effective behaviour by workers (Cooper 2012: 11). Professional boundaries are one of the defining characteristics that separates unskilled labour from a profession (Eraut 1994). According to Hashimoto (2006), the word ‘profession’ means to profess or declare that, as a professional, you will fulfil your duty in society, using expert knowledge, and are regulated, autonomous and accountable. A key characteristic of any professional body is its ability to make independent decisions about, and to have self-governance on, the definition, role, scope and duties of its members. Autonomy is derived from a Greek word meaning self-governance, and on a personal level, it relates to the ability to be in control of and make decisions about your own life (Rendtorff 2008). Professional autonomy relates to the ability to make decisions and judgements within the work environment, which are not absolute, but shaped and limited by guidelines or codes of ethics established by the profession (Hashimoto 2006). The eighty standards of proficiency, presented as individual chapters in this book, outline all the skills and knowledge needed to practise safely and effectively within the boundaries of our profession. These standards of proficiency are supported by a Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics and ‘each year registrants will be asked to pledge that they comply’ (SCWRB 2019: 1). The 27 ‘responsibilities’ in the Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics (2019) are categorised under three subheadings; Conduct, Performance and Ethics. Chapter 7 provides an overview of this document and looks specifically at the codes of conduct that are not already included in the eighty standards of proficiency. Accountability is being able to explain the decisions or actions you have made, or not taken, to the people who are directly affected by them (De Lissovoy 2013). Accountability is an important part of professionalisation and when people can stand over their decisions, practice becomes more transparent and safe. Regulation is about accountability to the service user, requiring discipline and adherence to the codes of ethics and conduct, and being answerable for our actions through a sense of individual responsibility. Regulation and accountability are part of a quality assurance process, which begins by setting standards, providing training and then implementing the standards and codes of conduct. This is a cyclical process and ‘as the profession develops, the Social Care Workers Registration Board is committed to continually reviewing these standards, in doing so, ensuring that they remain both relevant and comprehensive’ (SCWRB 2019: 2).

The Quality Assurance Cycle of Social Care Work (Adapted from Ellis & Whittington 1998)

Social care work is in a constant state of flux and we, as active participants of the quality assurance process, are always learning more about how to practise in a safe way. The quality assurance process begins on the first day of your social care education, as colleges prepare students to practise safely and effectively within the legal, ethical and practice boundaries of the profession. The inclusion of social care work in the 2005 Health and Social Care Professionals Act (DoHC 2005) was the catalyst for a series of changes in the education of social care workers, beginning with the redesign of programmes to ensure that the 80 standards of proficiency are the threshold learning outcomes for students. Social care educators will have to meet the standards outlined by SCWRB (2017a) in order to receive approval to continue educating social care workers. The Social Care Registration Board has ultimate power over the educational institutes, which require documentary evidence of a ‘high standard of professional education’, as indicated in sections 7, 27 and 38 of the 2005 Act. Educators will have to prove that they have suitably trained the designated professional to be a ‘fit and proper person, able to engage in the practice of the profession, with knowledge of the language necessary for practice’ (DoHC 2005: 11-28). The Social Care Registration Board has outlined that only educators eligible to register on the social care register (social care workers) will be permitted to teach or supervise the practice elements of the social care course. The protection of the title ‘social care work’ within the Health and Social Care Professionals Act 2005, the statutory registration of social care and the inclusion of workers as social care lecturers in the revised programmes, are all indicators of the professionalisation of social care work.

Legal, Ethical and Practice Boundaries

As well as being a characteristic of a profession that is regulated, autonomous and accountable, professional boundaries are important, because as a worker you have formal authority, and thus the potential to misuse your power and influence over service users. The focus of this chapter reflects the main aim of CORU, to ensure that the vulnerable public are protected by directing the worker on what he or she must do to keep people safe within legal, ethical and practice boundaries. Together, these professional boundaries reflect the values of social care and are influenced by changing ideas about how professionals should help others and what is safe practice (O’Leary et al. 2013).

To begin our discussion on professional boundaries in social care work, it is important to understand that the relationship is the core of your practice with others, not viewed as a tool (Lyons 2013; CORU 2017b), but as ‘the centre of it all’ (Ormond 2014: 252). Through spending time together, knowledge is gained on: the service user’s likes and dislikes; how to interpret communication cues; how to meet needs quickly and effectively; how to provide support appropriately; and being an advocate by communicating accurate information to others. Professional boundaries are integral to this relationship because there is a power imbalance (O’Leary et al. 2013) and as such, the potential to use actions, inactions or information to cause harm and abuse. The social care work relationship is a genuine connection between the service user and the worker, which is based on feelings of safety and trust (Smith 2009; Smith et al. 2013). This relationship is described by social care workers as needing focus and time, as being a difficult thing to establish, and experienced as personal as well as professional (Lyons 2017). Ensuring that professional boundaries reflect these values of practice, they must not become a barrier that separates the worker from the service user (O’Leary et al.2013), but one that maintains a relationship-based approach that is safe and genuine. This chapter continues with the boundaries that reflect laws and legislation, and codes of ethics and conduct. They are structured in the form of codes, rules and policies that can provide clear directions on what you ‘must’ and ‘must not’ do (SCWRB 2019), with the aim of helping workers to make safe decisions.

Legal Boundaries

Acting in the best interest of service users is the foundation of professional boundaries and as such, as a social care worker you are ‘always accountable for what you do, what you fail to do, and for your behaviour’ (SCWRB 2019: 14). Being able to practise safely within the legal boundaries of the social care profession begins with an awareness and understanding of all the relevant legislation (Cooper 2012). The Standards of Proficiency for Social Care Workers (SCWRB 2017b: 3) require workers to be aware of all ‘new and emerging legislation’ that is ‘relevant to the profession’. This statement (in standard D1 SOP13) allows for the inclusion of new or amended legislation that will be enacted during the social care worker’s long career. The Social Care Workers Registration Board (SCWRB 2017b) noted the importance of specific legal boundaries within the standards, which are illustrated in the table on the following page. Workers need to understand the boundaries of confidentiality and how this can sometimes be in conflict with whistleblowing, can risk assess, gain informed consent, and know the current legislation on data protection and the freedom of information. These are separate standards of proficiency and will be addressed in more detail in the corresponding chapters in this e-book. The table gives you some examples of the specific legal statutes that you must comply with in your duty of care to service user(s). A duty of care is central to social care practice, it is a commitment to reduce the risk of harm to the service user, other professionals and yourself. You can learn more about your professional duty to care in Chapter six.

|

Boundary from Standards of Proficiency |

Relevant Proficiency |

Chapter in e-book |

Example of Relevant Legislation You Need to Know and Understand |

|

Data protection |

D1 SOP 13 |

13 |

Data Protection Act 2018 |

|

Freedom of information |

D1 SOP 13 |

13 |

Freedom of Information Act 2014 |

|

Confidentiality |

D1 SOP 14 |

14 |

Freedom of Information Act 2014 Protected Disclosures Act 2014 Data Protection Act 2018 |

|

Whistleblowing |

D1 SOP 14 |

14 |

Protected Disclosures Act 2014 |

|

Informed consent and capacity |

D1 SOP 14 D1 SOP 15 |

15, 16 |

Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015 |

|

Risk assessments |

D3 SOP 12 |

52 |

Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 |

From the date a Bill is signed into law by the President, the legislation is enforceable and as such social care workers need to know what the legislation states and how it can impact on their practice with others (Kenneally & Tully 2013). It is also important to know the current policies that are provided as a guide for health and social care professionals on how to comply with the legislation, for example Tusla’s Protected Disclosures Policy and Procedure: A Guide for Whistleblowing on Alleged Wrongdoing (2016). Complying with the relevant legislation and the policy guidelines will underpin safe social care practice in each setting.

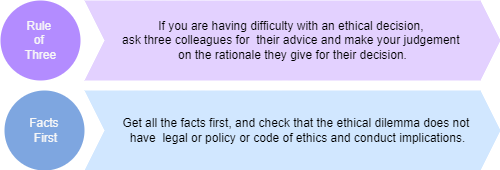

Ethical and Practice Boundaries

Current legislation and relevant policies, professional codes of conduct and ethics, taken together, will provide clear guidelines on what workers must and must not do. However, it is not always possible to have a rule or code to follow for every situation and experience in social care work and sometimes workers need to decide which ‘right’ or ‘code’ needs to take precedence. In these situations, professional boundaries appear liminal (Turner 1969), existing within the ‘grey zones’ of effective social care practice. The liminal grey zone exists because individual workers base their ethical decision-making on multiple factors including past experiences with the service user, and their own socialisation, upbringing, cultural influences, norms and values. These practice decisions and/or ethical dilemmas need careful thought and reflection and sometimes adjustment, to ensure they remain ethical, legal and in the best interest of the service user (Cooper 2012). Read the discussion topics below and write down your own answer before you have a discussion with your peers.

TASK 1

You are on placement in a day service for adults with an intellectual disability and on your day off you meet a service user (Tom) on the bus. What are your boundaries for the following dilemmas? Please provide a rationale for your decision.

(a) Tom gestures for you to sit beside him on the bus. Do you comply?

(b) Tom knows the area and asks you questions about where you live. Do you answer truthfully?

(c) You are both going shopping, and Tom asks if he can accompany you. Do you say yes?

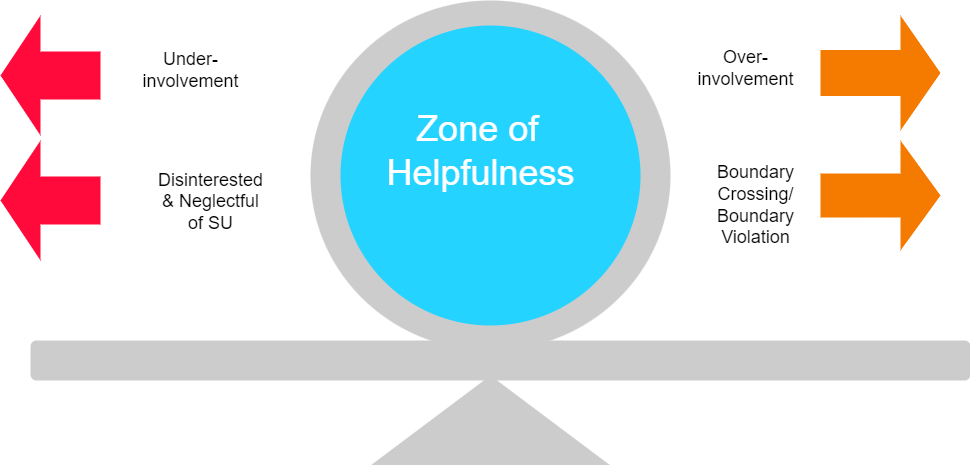

Navigating the Grey Zone of Boundaries: the Zone of Helpfulness

The discussion topics above are examples of some of the first boundaries students need to navigate on their practice placement. Some practice educators will have clear guidelines to help students know how to respond to common ethical dilemmas, responses which will be caring and also protect the service user from harm. Care is not simply dyadic – within the relationship between the worker and the other person – but is ‘the concern of living, active humans engaged in the processes of everyday living’, a daily practice that is ‘aimed at maintaining and continuing our world’ and the world of others (Tronto 1993: 104). Biestek (1961) argues that a care ethic includes the values of acceptance, self-determination, confidentiality, individualisation and a non-judgemental attitude. These values are supported by two principles, a purposeful expression of feelings and controlled emotional involvement, which together form the seven principles of practice, and guide the worker towards developing a relationship based on care and protection.

The continuum of professional behaviour is a framework designed originally to support nurses develop professional boundaries to navigate the grey zone of professional boundaries, and protect while providing care (NCSBN 1996). An adapted version of the zone of helpfulness framework is presented here as a guide for social care workers. This interpretation is different from the original; here the relationship is presented as central to our understanding of professional boundaries. The framework describes boundaries as existing within a continuum and the aim is to stay within the centre – the zone of helpfulness – where the boundaries are focused on what is best for the service user. The ‘healthy boundaries’ in the centre of the continuum (the zone of helpfulness), are consistent with a relationship-based approach, and provide protection within the experience of care. If the worker focuses too much ‘on what the boundary is, rather than why it is needed and how it is created’ (O’Leary et al. 2013: 135), they become under-involved. Alternatively, if they abuse their power, don’t comply with the codes of ethics and conduct or break the law, they are over-involved.

The zone of helpfulness is the space within the relationship between the social care worker and other, experienced when the service user feels heard, has personal autonomy, feels respected and understands how they are being protected by staff and the service. There is a clear understanding of what boundaries are in place to protect the service user and how and why they help. Chapter 21 provides more information on the role of the relationship in shaping our professional boundaries and provides advice on how to navigate those difficult ‘grey zones’ through the use of the Davidson model, which will also help you to stay in the helpful zone. Over-involvement can happen when the worker is not aware of their power and influence in the relationship and also does not comply with the boundaries of safe practice. The Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics (2019) provides clear guidelines on what workers must not do or they will be in breach of their duty of care. Over-involvement can also include experiences when the worker is trying to meet their own needs through their relationship with the service user. The only way to develop good practice boundaries is to maintain an openness to continuing professional development, through a process of ongoing learning about yourself and your practice with others. Ormond (2014) conceptualises social care practice as an openness to learn by a worker who is constantly questioning the internal and external influences and limits on practice and self. ‘Having an openness to learning is a prerequisite’ to social care practice, ‘the good enough worker never really reaches the point where they can say that they have arrived’ (Ormond 2014: 262). As a lived experience, social care is about learning through relationships, and the magic that can happen within a social care relationship based on trust, safety and genuine care. It also about people, who they are, and how their life journey has influenced them in how they present themselves today. The following practices will keep you rooted within the zone of helpfulness.

Under-involvement happens when the worker, in trying to adhere to practice boundaries, has become emotionally distant from the service user. The worker can appear uninterested in the service user and not relationship-focused, can act with an extreme focus on rules, can appear inconsistent, detached and superficial. Social care work requires more cognitive engagement in the ‘technologies of care’ (Smith 2009: 9), and in indirect practices (Fulcher & Ainsworth 2012), including paperwork, risk assessments, behaviour plans and reports. An increased level of report writing is viewed as the main culprit for taking social care workers away from spending time with service users in children’s residential care, and this may be an issue also faced by workers in different contexts (Mooney 2014). If time spent with the service users is not valued within the workplace, the worker may feel out of balance, distanced and separate from the service user, and incongruous to their care ethic. The responsibly to ensure that professional boundaries remain beneficial to the service user does not lie solely with the worker, but also includes the service, the regulators and policy-makers, as a shared duty to care. Social care workers need to talk to their line managers if they feel they are not able to spend quality time with service users to adequately meet their needs. The final sentence of the Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics (SCWRB 2019: 28) reminds social care workers to remember that we are accountable as autonomous practitioners, for what we do and fail to do. We also ask you to remember that as well as practising safely and effectively within the legal, ethical and practice boundaries, you will keep the relationship between you and the service user at the centre of your practice.

Students learn about professional boundaries within the placement setting by the practice educator.

- Give the student specific legislation and policies to read and ask them to indicate how these laws and policies protect the service users in this setting.

- Give the student an ethical dilemma from your setting and advise them on what are the best responses to give.

- If you do not already have guidelines on typical practice boundaries, set this as a task for the student and ask your colleagues to become involved.

Learning to navigate the grey zone of professional boundaries:

According to social care workers in different services (Lyons 2017), it takes years of practice before they began to feel more comfortable and confident in their acquired skills and knowledge and feel they are doing ‘effective practice’ using their professional boundaries. Workers described these ‘years of experience’ as a rite of passage (Turner 1969), through which social care practice is ‘learned’, and the social care worker identity claimed. Think about your own daily practice and how you stay in the zone of helpfulness. What are the biggest challenges for you to maintain a relationship based approach in your practice?

Task for the practice educator:

What are the important practice boundaries you have learned that have helped you navigate the grey zone in your service?

Primarily, workers use their relationships with others as a gauge of their ability as a worker and of their identity. This includes one-to-one relationship feedback with service users, team meetings, peer feedback and regular supervision. People judge themselves based on how they feel others are judging them, especially if the ‘others’ are of value (Erikson 1968). As an experienced worker, in the role of practice educator, what you say, and how you say it, will have an impact on the emerging professional identity of the student or newly qualified member of your team. Think about the feedback you are about to give the student and ask yourself what important message you learned about professional boundaries from your own practice placement and early work experiences.

Biestek, F. (1961) The Casework Relationship Unwin University Books.

Cooper, F. (2012) Professional Boundaries in Social Work and Social Care: A Practical Guide to Understanding, Maintaining and Managing your Professional Boundaries. London: Jessica Kingsley.

De Lissovoy, N. (2013) ‘Pedagogy of the impossible: Neoliberalism and the ideology of accountability’, Policy Futures in Education 11(4): 423-35.

DoHC (Department of Health and Children) (2005) The Health and Social Care Professionals Act. Dublin: Government Publications Office.

Ellis, R. and Whittington, D. (1998) Quality Assurance in Social Care. London: Arnold.

Eraut, M. (1994) Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. London: Falmer Press. Erikson, E. (1968) Identity: Youth and Crisis. London: Faber.

Frunza, A. (2018) ‘Philosophical Grounding of Ethics Expertise’ in S. Sandu and A. Frunza (eds), Ethical Issues in Social Work Practice. Hershey, USA: IGI Global.

Hashimoto, N. (2006) ‘Professional autonomy’, Japan Medical Association Journal 49(3): 125-7. Kenneally, A. and Tully, J. (2013) The Irish Legal System. Dublin: Clarus Press.

Lyons, D. (2013) ‘Learn about Your Self Before You Work with Others’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Lyons, D. (2017) ‘Social Care Workers in Ireland – Drawing on Diverse Representations and Experiences’, unpublished PhD thesis, University College Cork.

Mooney, D. (2014) ‘Waiting: Avoiding the Temptation to Jump In’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons (eds) Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 142-153). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

NCSBN (National Council of State Boards of Nursing, USA) (1996) Assuring Competence: A Regulatory Responsibility. Chicago, IL: National Council of State Boards of Nursing.

O’Leary, P., Tsui, M. and Ruch, G. (2013) ‘The boundaries of the social work relationship revisited: Towards a connected, inclusive and dynamic conceptualisation’, British Journal of Social Work 43(1): 135-53.

Ormond, P. (2014) ‘Thoughts on the Good Enough Worker’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons, Social Care Learning from Practice (pp. 251-63). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Rendtorff, J. D. (2008) ‘The Limitations and Accomplishments of Autonomy as a Basic Principle in Bioethics and Biolaw’ in D. Weisstub and G. Díaz Pintos (eds), Autonomy and Human Rights in Health Care: An International Perspective. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017a) Criteria for education and training programmes. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017b) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2019) Social Care Workers Registration Board code of professional conduct and ethics. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at https://coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for- social-care-workers.pdf.

Smith, M. (2009) Rethinking Residential Care: Positive Perspectives. Bristol: Policy Press.

Smith, M., Fulcher, L.C., and Doran, P. (2013) Residential Child Care in Practice: Making a Difference. Bristol: Policy Press.

Tronto, J. (1993) Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. London: Routledge. Turner, V. (1969) The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure. New York: Cornell University Press.

Tusla Child and Family Agency (2016) Protected Disclosures Policy and Procedure: A Guide for Whistleblowing on Alleged Wrongdoing. Dublin: Child and Family Agency.