Chapter 13 – Sarah Joyce (D1SOP13)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 13

Be aware of current data protection, freedom of information and other legislation relevant to the profession and be able to access new and emerging legislation

|

KEY TERMS Data protection Freedom of information Legislation Modern social care in Ireland

|

Social care is … empowering people to become the best version of themselves. |

In recent years there have been vast changes in social care in Ireland. What was once viewed as a vocation has now become seen as a broad profession. Social care is still based on caring for those who are vulnerable and marginalised in our society, but now it is underpinned by legislation and a professional title. The primary legislation underpinning social care in Ireland is the Health and Social Care Professionals Act 2005, which recognised ‘social care worker’ as a professional title, a pivotal moment in gaining professional recognition for social care workers. This shift to a professionalised sector ensures that service delivery is underpinned by legislation and accountability. One of the most recent changes to come into effect is how we use, store and share information.

Data Protection

In their day-to-day work, social care workers deal with large amounts of data, including information on service users and organisational information. The Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA) outlines how this information should be processed, in other words how we as social care workers use it. It is imperative to note that service users must consent to their personal data being processed (Tarafdar & Fay 2018). One example of information gathered by social care workers in the homeless sector is the holistic needs assessment (HNA). The HNA is a vital and comprehensive document that follows service users from service to service, enabling staff to have access to important information without service users having to re-tell their story, which is needlessly repetitive and sometimes difficult (Homeless Agency 2009:8).

The ‘rough sleeper count’ is an example of statistical data gathered by the Dublin Region Homeless Executive (DRHE) and Dublin City Council (DCC). The count is carried out twice a year by council and frontline staff of various organisations, including the Peter McVerry Trust, Simon and Focus Ireland. Staff are split into teams and each team is given a catchment area to cover. The teams count the number of people sleeping rough on that night and the information is then broken down into different categories. For example, in the 2018 count, 110 people were identified as ‘rough sleepers’: 84% were male, and 16% female; 42% were non-Irish nationals, 58% were Irish nationals, and 31 individuals did not reveal their nationality. This information is vital in identifying how many people are sleeping rough at any one time (alongside increases/decreases in rough sleeping) and what resources are required to assist rough sleepers to exit homelessness (DRHE 2018).

As we can see with the rough sleeper count, inter-agency work is imperative in the homeless sector. People who are homeless often have multiple complex needs stemming from housing needs – addiction, mental health, behavioural needs, dual diagnosis. It is almost impossible for one person or one organisation to meet all those needs, so a lot of inter-agency work is required. When working together, it is vital that organisations adhere to the Data Protection Act and are mindful of never using clients’ names when sharing information; instead, initials should be used. Emails containing sensitive information should always be password-protected.

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into effect in May 2018, is the most important change in data privacy regulation in 20 years. It places a strong emphasis on consent and has strengthened how consent is gathered before information can be exchanged between organisations. When a client enters a service, they are asked to sign a consent form, which allows staff to liaise with other organisations on behalf of their client, for example the client’s GP, or their local authority. It is important to explain to the client that this consent is to enable staff to advocate on their behalf with other organisations. Clients must be made aware that this consent can be withdrawn at any time. There are penalties in place for any organisations that breach the regulations. It is a positive step for the protection of data belonging to everyone, especially those who are most vulnerable (European Commission 2019).

Task 1

The Security Company Tessian list 18 of the biggest GDPR fines in the EU in 2020-2021. Read the list and discuss why the fine was given?

https://www.tessian.com/blog/biggest-gdpr-fines-2020/

Freedom of Information

The Freedom of Information Act 2014 gives people autonomy over their personal information.It allows any member of the public to access personal information about them held by government bodies, bodies receiving state funding, and any other bodies that may hold personal information relating to that individual. It also allows people to amend their information where necessary (Government of Ireland 2019).

Dublin City Council’s Corporate Plan (part of the Strategic Framework For Action 2015-2019) found that in 2016 there were 80 responses to freedom of information (FOI) and data protection requests from the homeless sector (Pyne 2017). FOI requests can be made for numerous reasons, including: to access official records held by government departments or other public bodies; to update or correct personal data; or to find out why a decision about a person has been made by a public body. If a person is exiting homeless services, they may wish to access what information is in the public domain about them from their time in homeless services. This is their right and a request can be made in writing or via email. The following information must be included in the request: be specific that you are making an FOI request; clarify exactly what information you are requesting; and supply a copy of current identification (Government of Ireland 2019).

An FOI application form for the HSE is shown below.

|

Title of Form and destination of the request |

||

|

Copy to: Decision Maker [ ] |

FOI Call Centre [ ] |

Application Ref No: |

|

Health Service Executive |

|

|

|

Request for Access to Records |

|

|

|

Freedom of Information Act 2014 |

|

|

|

1. Details of Requester (Please Use Block Capitals) |

|||

|

Surname |

Address |

||

|

Maiden Name |

|

||

|

First Name(s) |

|

||

|

Date of Birth |

|

||

|

Tel (home): |

Tel (business): |

Fax: |

E-mail: |

|

2. Personal Information (If request is for non-personal information, go to 3. below) |

|

Before you are given access to your personal information, you will need to provide proof of your identity. A copy of the identifying document accompanies this Form: [ ] Yes [ ] No (tick one) |

|

If you are requesting personal information in respect of another person, the consent of that person is also required. A copy of this consent accompanies this Form: [ ] Yes [ ] No (tick one) |

|

3. My preferred Form of Access is: (please tick one) |

|

(a) To receive photocopies [ ] |

|

(b) To inspect the original record [ ] |

|

(c) Other format [ ] (Please specify): |

|

4. Application |

|

|

I request administrative access to the information/records detailed overleaf: [ ] (please tick) |

|

|

If this is not feasible, I request access under Section 12 of the |

|

|

Freedom of Information Act 2014: [ ] (please tick) |

|

|

Signed: |

Date: |

|

5. For Office Use Only |

|||

|

|

Admin Access |

FOI Access |

|

|

Date Received |

|

|

Signed: |

|

Date Acknowledged |

|

|

Signed: |

|

Identity Confirmed |

[ ] Yes |

[ ] No |

Signed: |

|

Consent Verified |

[ ] Yes |

[ ] No |

Signed: |

|

Access Granted |

[ ] Yes |

[ ] No |

Signed: |

|

|

|

|

Date: |

|

6. Details of Information/Records Requested |

|

Describe the records as precisely as you can. If you are requesting personal information, please state as accurately as you can the date the record was created, your exact name and address at the time the record was created, and the Department/Hospital/Clinic attended within the HSE. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Please note: to help in processing your request, the information on this Form will be stored in electronic format.

Case Study 1

An incident occurs in a homeless hostel. A service user is involved in a physical altercation with another service user. Two staff are alerted to the incident when they hear shouting. They try to calm down the two service users and find out what caused the altercation. Before the staff have defused the situation, one of the service users leaves the building. The second service user follows and a second verbal altercation ensues outside the service. After a calm word from the staff one of the service users returns inside the building and the second leaves for a walk to cool down.

TASK 2

Write up an incident report for the case study.

When writing up the incident report, it is vital to pay attention to facts. At what time did the staff hear the shouting? What did they hear being said? How did the staff approach the situation? What did they see when they got to the service users? Who else was present? When were management informed? How did the staff debrief afterwards? What was the follow-up?

It is important to archive all information in accordance with the organisation’s policies. Most records are held for between two and ten years, depending on the content. After this time they are destroyed. The retention of data has numerous uses, from government research to historic use (how data is analysed over time, generating trends) (Geraghty 2014).

Legislation

Legislation begins its life as a bill, often proposed by government. The bill can commence in either the Dáil or the Seanad, but it must be passed by both Houses to become law. The contents of the bill are discussed by government before it is introduced to the Dáil. The government will also consult with groups that the bill may affect, for example lobbyists, voluntary organisations and the public. Occasionally, a Green Paper is drafted – this is a discussion paper inviting ideas from the groups mentioned above. The report stage follows, when the bill is examined section by section. The bill is then sent to the Dáil, where it is voted on. If it is passed, the bill goes to the Seanad, and the Seanad has 90 days to pass, reject or return the bill. Once passed, the bill becomes law (Oireachtas 2020).

As social care is a large and diverse sector, a number of laws and regulations apply to it. The primary legislation underpinning social care is the Health and Social Care Professionals Act 2005. The development of CORU (Ireland’s multi-profession health regulator) was broadened to include the Social Care Workers Registration Board in 2015 and this was instrumental in assuring that social care is underpinned by the highest standards possible (Power & D’Arcy 2017).

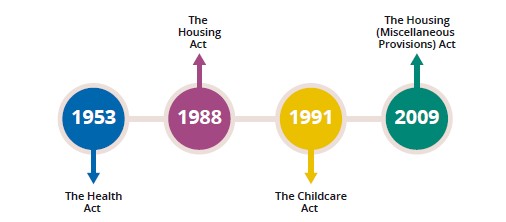

Some legislation relates specifically to homelessness. According to the DRHE, key legislation relating to homelessness in Ireland includes the Health Act 1953, the Housing Act 1988, the Childcare Act 1991 and the Housing (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2009. The Housing Act 1988 was the first Act to legally define homelessness. The Act states that a person is considered homeless if:

a) there is no accommodation available which, in the opinion of the authority, he, together with any other person who normally resides with him or who might reasonably be expected to reside with him, can reasonably occupy or remain in occupation of,

b) he is living in a hospital, county home, night shelter or other such institution, and is so living because he has no accommodation of the kind referred to in paragraph (a), and

c) he cannot provide accommodation from his own resources.

For information on all key legislation relating to homelessness, see www.homelessdublin.ie/info/policy.

Case Study 2

Joe is 42 and originally from Dublin City. He served a four-year custodial sentence for a drug offence in a prison in Dublin. While he was in prison, Joe tackled his addiction and is now over three years drug free. He is determined to turn his life around and turn his back on criminality. Before he was released from prison he had a factory job lined up through a friend. Prior to his release he reached out to family to see if he could stay with them on his release. Unfortunately, there was nowhere suitable for him to stay. As a result, Joe links in with his local county council to try to source a bed for when he is released. He is given a bed in a one-night-only hostel. He is told he will need to use the Freephone service to book back in each day and see if a bed is available. Joe is really worried that this will affect his sobriety and his job prospects post-release.

TASK 3

Discuss the above case study. What type of legislation would support Joe on release? Where could he go for information and support?

Recommendations were made by two different Oireachtas committees to introduce emergency legislation in an attempt to tackle the homeless crisis. These recommendations included rent freezes, restricting the sale of rental homes, and ending the use of ‘one night only’ emergency accommodation. This is an example of recommendations that may emerge to become legislation in the future (Holland 2019).

TASK 4

Go online and type in your name. Find some information that is available about you.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

Divide the class into different groups resembling the different sectors of social care. Can the groups find out the legislation related to each sector?

References

DRHE (Dublin Region Homeless Executive) (2018) ‘Dublin Region Homeless Executive Confirms the Official Spring Rough Sleeping Count’. DRHE [online] <https://www.homelessdublin.ie/our-work/ news/dublin-region-homeless-executive-confirms-the-official-spring-rough-sleeping-count-2018> [accessed 2 February 2020].

DRHE (2020) Policy and Legislation. Dublin Region Homeless Executive [online] <https://www.homelessdublin.ie/info/policy> [accessed 19 January 2020].

European Commission (2019) ‘EU Data Protection Rules’ [online] <https://ec.europa.eu/info/priorities/ justice-and-fundamental-rights/data-protection/2018-reform-eu-data-protection-rules/eu-data- protection-rules_en> [accessed 13 December 2019].

Geraghty, R. (2014) ‘Attitudes to qualitative archiving in Ireland: findings from a consultation with the Irish social science community’, Studia Socjologiczne, 214(3), 187-201.

Government of Ireland (2019). Freedom of Information Ireland website <https://foi.gov.ie> [Accessed 13 Dec. 2019].

Holland, K. (2019) ‘Oireachtas committees say emergency legislation needed to tackle homelessness’. Irish Times [online] <https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/oireachtas-committees-say- emergency-legislation-needed-to-tackle-homelessness-1.4083307> [accessed 19 January 2020].

Homeless Agency (2009) Case Management at the Core. Dublin: Homeless Agency, Parkgate Hall. HSE (Health Service Executive) (2020) Making a Request Under the Freedom of Information Act [online] <https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/yourhealthservice/info/foi/making-a-request/> [accessed 15 November 2020].

Oireachtas (2020). Houses of the Oireachtas – How Laws are Made [online] <https://www.oireachtas. ie/en/visit-and-learn/how-parliament-works/how-laws-are-made/> [accessed 15 November 2020].

Power, M. and D’Arcy, M.P. (2017) Statutory Registration Awareness amongst Social Care Workers Survey. Social Care Ireland.Pyne, M. (2017) Progress Report on Second Year of the Corporate Plan 2015-2019. Dublin City Council. Tarafdar, S.A. and Fay, M. (2018) ‘Freedom of Information and Data Protection Acts’, InnovAiT, 11(1) 48-54.