Chapter 15 – Janine Zube (D1SOP15)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 15

Be able to gain informed consent to carry out assessments or provide interventions and document evidence that consent has been obtained.

|

KEY TERMS Understanding the role of social care workers Variety of contexts (roles/settings) Documenting informed consent Interventions as planned practice Assessments

|

Social care is … an invitation into a person’s home and life, to support them to reach their goals. Irrespective of who pays your wages, the HSE or Tusla, for example, the service user is your employer. |

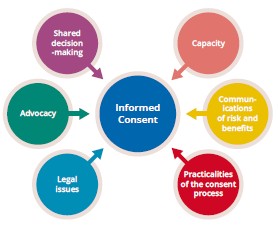

Interventions and assessments are central to planned social care practice with service users, and efforts are made to gain service users’ informed consent. Service users may be living in long-term care, such as disability or homeless services, or in community supported living. It must be noted that in some sectors informed consent may not be given, or required, for example in special care. This chapter begins with an introduction to informed consent and continues by looking at the role of the social care worker and the different tasks/interventions for which consent is needed. This chapter also describes the process of obtaining and documenting consent. Of the eighty standards of proficiency, two relate to informed consent. This chapter focuses on obtaining and documenting informed consent and Chapter 16 (Domain 1 SOP 16) provides an overview of the legislation and guidelines governing informed consent for people with a lack of capacity.

Task 1

Read Chapter 16 for an understanding of the legislation and guidelines governing informed consent for people with a lack of capacity.

Informed Consent

If your work involves supporting and caring for people, you must have the person’s consent to what you propose to do with or for them, for example carrying out personal care. This respect for people’s rights to determine what happens to their own bodies and life is a fundamental part of good practice and also a legal requirement. Adults are always presumed to have capacity to make healthcare decisions, unless the opposite has been demonstrated. However, anyone can experience temporary lack of capacity due to severe illness, loss of consciousness or other similar circumstances at some stage in their life. If there is sufficient reason to question the presumption of capacity, the person’s capacity should be assessed. Social care workers have a duty to maximise capacity and all efforts must be made to support individuals in making decisions for themselves where this is possible.

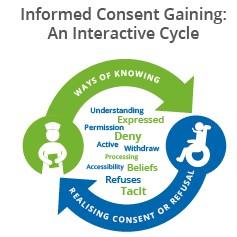

HIQA (2020) states that informed consent is a process for obtaining permission or agreement before conducting any intervention, receipt or use of a service or participation in research, following a process of communication in which a person using a service has received enough information to enable him or her to understand the nature, potential risks and benefits of the proposed intervention or service on or for disclosing a person’s information.

Informed consent is ‘freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her’ (European Parliament 2016).

While this is all good, you may ask yourself how you will be able to obtain informed consent from a service user who uses alternative forms of communication. As social care workers we always assume capacity of the person, even when someone requires support with his/her decision-making. It is important to document that informed consent has been given for an intervention and services, healthcare organisations and service providers have traditionally used paper-based consent forms on which intervention, services, procedure, together with risks and benefits, are noted.

The first step is to get to know the person and build a relationship. Once you have familiarised yourself with the means and communication method of the person, you will be able to adjust and amend information to the format of preferred communication.

TASK 2

You can make information accessible by using picture-supported information pamphlets or short video clips. Watch the following video and considerwhat information you could redesign for the benefit of your service users: https://fb.watch/5-DjAkbiBJ/.

Interventions

If you work in residential settings, you will be expected to support a person in daily life activities including personal care. It important to respect the choice and preference of a person when providing personal care. Supporting a person with such intimate care always requires informed consent. Consent should also be gained for alternative arrangements, such as if a preferred support gender/person is not available. A person’s decision-making and comprehension can be supported by additional user-friendly and accessible information, consent can be completed remotely, and the process can become paperless. One form of digital consent is dynamic consent, which invites service participants to provide consent in a granular way, and makes it easier for them to withdraw consent if they wish. This can mean that you as the professional has to become creative and inventive, making information accessible through the preferred choice of communication. This could be developing an easy-to-read version which is picture-supported or having a group discussion on particular subjects. The more information a person receives and understands, the better able they will be to make an informed decision.

You will also support people in making choices regarding their life and future. Supporting a person with profound disability will require a more adaptive format of giving informed consent. You may have to consult with someone who knows the person you support best or link in with an appointed independent advocate. A good example is the current pandemic. While we are all experiencing difficulties living with the pandemic and its restrictions, it is certainly much harder for service participants and vulnerable service users in our communities. Some of the hardest decisions our service users had to make was giving informed consent to cocoon and, more recently, consenting to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

This has presented a specific challenge across services providing support for the elderly, people with disabilities and people of all ages with acquired disabilities. You may have to support a person who presents with momentary incapacity. Social care workers may have been suddenly presented with opinions from family members, and we all have our own opinion on vaccines and the necessity of protection against COVID-19. However, it is important that the person has all information and makes an informed decision. When presented with differences of opinion and the aspect of protection, it is crucial to document all interaction with the person. For example, a social care worker provided support to a person with an acquired brain injury by giving accessible information to the person. To obtain informed consent a series of ten questions around COVID-19 and the vaccine were developed, such as:

- Do you know about COVID-19?

- Would you like a vaccine which could protect you from COVID-19?

While the person initially declined the vaccine, it needed to be established whether they really understood what, in general, is meant by a vaccine. Reviewing medical records, if available, or consulting with a person who knows your service user well may give an indication of your service user’s understanding of the concept of vaccines. Further, tailing questions such as ‘Did you get a vaccine for polio or tuberculosis as a child?’ might help to establish whether the person has received a vaccine before.

Once the ten questions were established a conversational interaction about COVID-19 was conducted with the person. To provide credibility and demonstrate informed consent, the ten questions were asked in the same order twenty times. During the first five conversations, written documentation of the conversation was completed with the person. During the remaining fifteen, informed consent was given by the person to record four conversations establishing informed consent and the wish of the person to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

Visual supports relating to vaccines can also help the person to understand the issue. The HSE website has a list of these (see www.hse.ie/eng/services/covid-19-resources-and-translations/covid-19-vaccine- materials/covid19-vaccine-easy-read-and-accessible-information/).

Understanding the Role of the Social Care Worker

Social care work is a very diverse role which involves working with people in a practical way through general day-to-day activities in a range of settings. This includes working with people with disabilities, mental health problems, minority groups, ethnically and gender-diverse individuals and groups in private and public settings.

A social care worker will, in a holistic and client-centred approach, develop personal growth and care plans for the person or group they support. They might be supporting a homeless person to find work or somewhere to live, teaching a service user with a disability to be more independent or helping an adolescent who has lived in care to adapt to life as a self-sufficient adult. More, in some settings or at times, a social care worker may become involved in working alongside the service user’s family to ensure his or her natural support network (family) understand and support the development plan of the individual. Social care workers will stay in touch with other relevant stakeholders such as individual support agencies and multidisciplinary clinicians or liaise with other professionals on the service user’s behalf. At times, the role requires assertiveness and the ability to provide ‘tough love’. Sometimes, service users will need to be told ‘no’ and have alternative methods demonstrated, especially children and adolescents who need support with behaviour management.

TASK 3

Think of how you would experience some of the difficulties your service users (on placement or within your service) are experiencing. Focus on one issue and think of a meaningful intervention. Include a list of all the people who could be involved to support the person receiving the intervention.

Supervision is essential during this time, and engaging in frequent supervision sessions will ensure that our practice is client-centred and rights-based.

Variety of Contexts (Roles/Settings)

If you work with people with disabilities it is important to highlight that community participation should be inclusive and meaningful. If you ever thought your research days were over once you completed your undergraduate thesis, think again! The better your research skills are, the better you will be at sourcing inexpensive activities for people. In the case of a person with disability, joining a group predominantly representing people with disability may be a good start. The true skill is including all members of the community to either set up or join a common interest group. Suddenly you find yourself in the role of negotiation, or mediating between interest groups. Another skill to develop over time is how to access funding. This involves skills in accounting, being business savvy and promoting or marketing your project or supporting a service participant to take on a fundraising project.

You’ll need to be well organised, confident and able to cope in potentially challenging situations.

You may find yourself supporting a person during a difficult time or after being admitted to hospital. This may require you to stay in the environment, organising and co-ordinating supports, engaging and informing other stakeholders, such as hospital personnel, who may not have the experience and resources to support a person with particular needs. Leadership and management skills are important as you will liaise with a number of people involved in a person’s network, advocating and leading the delivery of care.

You might imagine that you will most often link with medical or clinically trained stakeholders, but you might find yourself supporting an individual accessing housing through county councils; applying to the Department of Social Protection for financial supports; leading multidisciplinary case conferences; or dealing with family conflicts.

As a social care worker you may work with children, young people, families and/or significant others, social work teams, other healthcare providers and government agencies, schools, training agencies and community groups to care for, protect, and support vulnerable or dependent service users, individually or in groups, in conjunction with the wider multidisciplinary team and other relevant agencies that aim to ensure the welfare of service participants and you will act as an advocate as appropriate. You will contribute to the planning and evaluation of individualised and group programmes of care, which are based on needs identified in a holistic approach with your service user and others, and delivered through day-to-day shared life experiences.

In residential, day services, community or special care settings you will be part of a team providing a safe, caring environment for service participants – children, young people and adults – with the primary aim of providing the intervention necessary to address the issues that are preventing them from living at home or of preparing them to live independently with the support of aftercare services or individualised services.

Interventions as Planned Practice

Because we are working with people in all their individuality we must ensure that our skills develop and grow over time. It is important to form positive relationships with service users built on time and trust.

You will learn all about theories and approaches that will become your basic tool box for your career as a social care worker when you graduate from college. These skills will be observing, analysing and assessing situations and people’s needs. However, not every person you work with will understand the traditional methods of communication, learning and interaction. Naturally, due to the limited resources available, you will become creative in sourcing material, accessing community initiatives or even shaping entrepreneurial skills; not reinventing the wheel, but making it more efficient, working to the needs and abilities of your key person/group.

Developing and implementing creative activities fulfil a variety of purposes, including: relationship development; increasing self-esteem; improving hand-eye co-ordination; and stimulating memory. These are all used in healthcare, the disability services, care for the elderly and the youth and community sector. Creative and recreational intervention are designed to meet the individual needs of service users within these sectors.

You will conduct assessments based on the needs of the person you support. At times this may be challenging due to a variety of reasons, for example: a limited ability to communicate via traditional communication methods; being unsure of one’s own wants and desires; lack of confidence; and past experiences. For example, a person with a severe disability may communicate in a non-verbal way. To support this person you have to get to know their likes and dislikes by finding a common language to communicate, for example by using pictures, audio or sensory supports. As key worker for this person you will become their interpreter and advocate. You will need to find the most natural way for this person to participate in the community and engage in activities of their choice with their peers. The need for social participation could involve bringing together people experiencing isolation for various reasons, such as mature age, having recently migrated or relocated, or mental health issues.

Challenging times, such as the current pandemic, demand creative solutions and adjusting your skills to develop, implement and deliver meaningful interventions. With limited physical contact you will find yourself having to use all means available to you to reach and engage with your service user(s). Some of the people you support will be tech savvy, but others may be hard to reach or may not have the means or technical advantages to stay in touch.

This proficiency is based on rights-based practice, therefore the importance of engaging with service users is discussed. Rights-based practice is a positive development; however, resources need to be available and accessible for workers to create a rights-based practice culture in order to ‘gain informed consent to carry out assessments or provide interventions and document evidence that consent has been obtained’.

Tips for Students

- Be open to enter into a journey with your key service user/group, accompany their flow and speed to discover and support the growth and development of the individual/group. Enable the person/group to lead and develop the skills needed to reach personal goals.

- When planning your intervention or project, be patient with yourself.

- Building a relationship with your key service user/focus group is paramount to your intervention being successful.

- Think of a meaningful intervention for the person/group. Vitally, match the intervention to their ability.

- Use SMART goal to help guide goal setting. SMART is an acronym that stands for: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-based.

- Therefore, a SMART goal incorporates all these criteria to help focus your efforts and increase the chances of achieving your goal.

- Use and engage actively in all your supervisions with your practice supervisor.

- Last but not least, be kind to yourself during your journey. Reflect on your abilities as well as on your limitations and reach out to your practice and/or college supervisor

- Remember, a placement is a safe place to explore and develop your skill with the support of your placement supervisor.

Tips for Practice Educators

Engage the student in role play or introduction of attended group in placement (e.g., disability/aftercare).

Explore with the student their strengths and areas of interest areas. Find opportunities for them to familiarise themselves and engage with services and service participants.

Facilitate and create opportunities for students to experiences the difficulties service participants may face every day (e.g., engaging in activities while blindfold, using a wheelchair to explore daily activities, using ear covers).

Enable and engage student in reflective practice. Skill growth will come with practice. One practical exercise may be handing students particular responsibilities such as daily documentation reports or communication entries.

Be honest with your student if an invention/project may not be timely or realistic.

References

CORU (2020) Update on the Registration of Social Care Workers. Available at <https://coru.ie/about- us/registration-boards/social-care-workers-registration-board/updates-on-the-social-care-workers- registration-board/update-on-the-registration-of-social-care-workers/#:~:text=Social%20care%20 work%20is%20a,marginalisation%2C%20disadvantage%20or%20special%20needs>.

European Parliament (2016) Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and the Council. Available at <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eur/2016/679/contents>.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2016) Supporting People’s Autonomy: A Guidance Document. Available at <https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2017-01/Supporting- Peoples-Autonomy.pdf>.

HIQA (2020) International Review of Consent Models for the Collection, Use and Sharing of Health Information. Available at <https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2020-02/International- Review%E2%80%93consent-models-for-health-information.pdf>.