Chapter 16 – Moira O’Neill (D1SOP16)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 16

Be aware of current legislation and guidelines related to informed consent for individuals with lack of capacity.

|

KEY TERMS Consent Informed consent Lack of capacity |

Social care is … being an extra support to a person in their time of need, being their information box, a spokesperson for them, a cheerleader behind them. Social care is helping service users achieve their goals, whether large or small, and the belief that they have the tools within which need to be realised in order that they can do what is necessary to bring about positive change in their lives and the lives of their loved ones. |

Consent

Understanding that the area of consent and capacity to consent is extremely complex is paramount when ensuring the rights of the service user. A lack of capacity can make those particular service users in our care who require support even more vulnerable as we endeavour to work with a human rights-based approach, ensuring that the rights of the service user are upheld and their needs are met. As students we are taught that each service user is an individual and to support their needs accordingly and to ensure that they are an active participant in their care needs.

Development within the area of social care gave rise to CORU being established to ‘protect, guide and inform the public’ (SCWRB 2017: 2), no more than the service users, particularly those with a lack of capacity, who avail of the supports available. This growth saw the views of the service user being incorporated into care plans where historically their voices may not have always been heard and their consent not sought.

Many service users are extremely vulnerable members of society who experience adversity and access services for support to tap into and develop resiliency skills. Assistance is offered in areas such as youth and family services, mental health, homelessness, addiction and disability. Larkin (2009) highlights the difficulty in defining the term ‘vulnerable’, ultimately concluding that vulnerable individuals are those in society who are at risk or require support.

Nonetheless, we do not need to class those service users who lack the capacity to consent as completely vulnerable, as they can always make decisions regarding some aspects of their lives. We need to ask ourselves what we, as social care workers, can do in our duty of care to support their rights and empower them, while negating potential risk factors, to ensure that they are as independent as possible.

This chapter will discuss the role of social care workers and legislation in Ireland governing lack of capacity, which in turn governs organisational policies which are then interpreted and converted into practice by social care workers. There are many policies which often work in conjunction with one another to ensure the safety of all service users, especially those who are deemed to lack capacity. This allows them to live a life of their own choosing, safely, and with support and advocacy where needed from a social care worker.

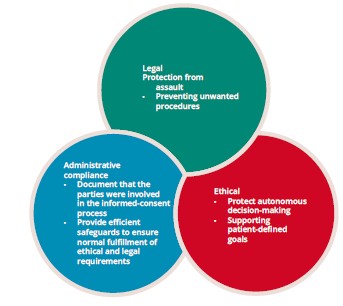

The role of a social care worker is multifaceted and can often be challenging as a result. Their work entails a number of intertwined factors – legal aspects, ethical considerations and administrative compliance – as set out in the Venn diagram below.

Hall et al. state that ‘informed consent is primarily a legal and ethical concept’ (2012: 533), discussing how autonomy can in fact be afforded to the service user in providing person-centred care that adheres to the legal and policy guidelines and requirements. Charleton (2007) states that ‘ethics is central to human living’ (p.2) and identifies an overlap in ethics and law for people with lack of capacity requiring social care intervention; where certain decisions cannot be made by the service user and ultimately rest with another, ethical considerations surrounding information, consent and confidentiality will arise.

Sugarman et al. (1999) discusses how the requirement for obtaining informed consent is an expected part of practice and questions whether this consent is achieved meaningfully amidst the laws, professional guidelines and policies of the social care organisations. SCWRB (2017) introduced its proficiencies as a way to raise the bar for social care workers in providing intervention to those who access their services.

Informed consent is described in the Health Service Executive (HSE) National Consent Policy as a service user having a ‘sufficient understanding’ (2019: 53) of what is being proposed, while capacity is defined as the ‘ability to understand the nature and consequences of a decision in the context of available choices at the time the decision is to be made (2019: 12). The test is whether the service user can fully comprehend the intervention at hand and give their informed consent and even be aware of their right to withdraw their consent if they disagree at a later time.

We must provide service users with accurate information and choice, and we should leave our own beliefs and values at the door. This approach will support the service user’s autonomy and self-efficacy in their own culture of norms, values and beliefs. It is imperative that we as social care workers are working to empower the service user so that an open system of communication can be used to build valued relationships between the service user’s family members, the services being accessed and the interventions being applied to ensure that the care provided to the service user is wholly person-centred.

The cornerstone of social care work is interpersonal relationships between the service user and the social care worker. Communication is a key element in developing trusting relationships and most important in good practice when seeking consent to interventions, and it should be an ongoing process. A service user will be more inclined to seek advice from and listen to their social care worker once a relationship has been developed that taps into the core conditions to encourage a service user’s own potential.

Fyson and Cromby (2013) state that policy guidance ‘focuses on the relationship between choice, empowerment and risk;is concerned to identify clear lines of accountability for decisions taken’ (p.1168) and is at thecrux of this proficiency. Social care provision has moved from a ‘one size fits all’ approach with the realisation that all service users are unique and require individual care plans to cater for their needs. A service user must be afforded the opportunity of deciding what is best for themselves. It is important to balance the service user’s right to make decisions regarding their own care and risk management in ensuring they are not a danger to themselves and to others. The person might feel very capable and able-bodied; however, if there is an overwhelming risk to their health and wellbeing, services might need to intervene.

There are two threads under Proficiency 1.16 regarding lack of capacity: children; and service users with diminished capacity. Under Irish law, an individual is deemed to have a lack of capacity to consent until they have attained the age of majority, which is stated to be the age of 18, unless they have been married prior to this age (Age of Majority Act 1985).

However, Section 23 of the Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act 1997 states that the ‘effective consent’ of a minor who is 16 years of age or older allows them to make decisions regarding surgical, medical and dental treatments.

Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child advises that it is the state’s responsibility to ‘assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views, the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child’ (UN 1990).

Other factors, set out in the MCI (Medical Council of Ireland) publication on the doctrine of informed consent, include disclosure, comprehension, voluntariness, competence and agreement (2008: 12). What this means in practice is that the service user is given information regarding the intervention, that they are seen to understand the intervention, that they partake in it without being pressurised, of their own free will, with surety.

However, there is an exception to this, which is transferred to guidelines and policy; information can be withheld from the child under a ‘therapeutic privilege’ or ‘doctrine of necessity’ clause (HSE 2018b: 5). One might appear to contradict the other. This particular clause implemented by the HSE provides that the wishes of the parents will be respected in the level of information provided to their child; however, this is in direct conflict with policies to empower the minor service user and may present an opportunity for a social care worker in advocating for their minor service user in line with Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures (DCYA 2014).

Children are deemed not to have the capacity to make decisions themselves because they are viewed as being incapable, by virtue of their age, of having the cognitive development to do so. Difficulties can therefore arise for parents and guardians where their growing child wishes to become more autonomous in their care plan or indeed withdraw their consent for intervention as a whole.

Social care providers will have set out specific policies regarding consent; for example, the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) provides a Parental Consent Policy (HSE 2018) which outlines best practice in providing information to explain the proposed treatment, why it is required, the benefits of it to the child, alternatives and risks to include consequences of not proceeding with the treatment plan as proposed.

Case Study 1

A young service user wishes to come off their medication as they feel overtired and sluggish in the evening. The parent who has consented to treatment would prefer for them to continue on the same dose as they are getting good reports from the child’s school about their attention in class.

As a social care worker, how would you approach this scenario to cater for the wishes of the service user?

Having considered this scenario myself one thing that I would do is refer to the National Consent Policy: Part 2, particularly Section 4. I would give the young service user an opportunity of voicing their concerns. I would then be the child’s voice and show that they are being listened to and heard in advocating on their behalf to their parent and then, during the multidisciplinary team meeting, to the psychiatrist prescribing the medication. One must work with the suggestions of the team in the decision-making process of assessing the risks and benefits for the service user and discuss matters arising with the parent of the child in reaching a solution that works for the young service user.

The Mental Health Act 2001 makes provision to allow the state to be appointed to act where a child’s parent or guardian is deemed to have failed in their responsibilities to that child, and not just by reason of the child’s own mental capacity. That child then becomes a ward of court, and decisions regarding the child’s welfare rest with a person appointed best placed to make those decisions, known as their ‘committee’.

Assisted Decision-Making Capacity Act 2015

Prior to the introduction of the Assisted Decision-Making Capacity Act 2015, applications for wardship could also be made for individuals who were, or who had become, incapable of making decisions regarding their own welfare and wellbeing. If their incapacity was certified by medical professionals, the court would assume responsibility for them. A person known to them could be appointed as their committee and thereafter be able to make decisions relating to the ward’s medical treatment and financial decisions. Such practice was governed by the Lunacy Regulation (Ireland) Act 1871, depriving people with disabilities of their constitutional rights, an Act which has since been repealed by the Assisted Decision-Making Capacity Act 2015.

Moving forward, the court will appoint decision-making assistants or co-decision-makers who will support the person whose capacity has diminished. The ward will be re-assessed and they will be transferred to one of the other new supports offered by the Courts Service. This move is designed to uphold the rights of individuals and support their decision-making capacity in areas within their capability and to recognise areas where they require the assistance of their decision-making assistant or co-decision-maker as appropriate.

The Assisted Decision-Making Capacity Act (2015) sets the test of a person’s capacity. The 2015 Act was enacted into law following many developments, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006); the Principles Concerning Continuing Powers of Attorney and Advance Directives for Incapacity; and Promotion of Human Rights of Older Persons (Kinsella & Harrison 2016: 34-5). These developments paved the way for allowing service users to resume the right to, and recognised their abilities to, make choices for themselves regarding their care and their wishes to provide self-determination.

Human Rights

Another example of lack of capacity is individuals with intellectual disabilities. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that ‘all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’ (UN 1948: 4). Degener states that while, as humans, we have our rights from birth, individuals with disabilities have traditionally had those rights withheld in what is seen as ‘a form of protection – a form of caretaking’ (2017: 5).

Article 1 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which was ratified in Ireland in 2017, states:

‘The purpose of the present Convention is to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity.

‘Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others’ (UN 2006).

However, capacity to consent is dynamic; if a person is shown not to have the capacity to consent in one particular area of their care it does not mean that there is a lack of capacity to consent on the decisions and interventions pertaining to other areas of their lives. Historically, what may have been a blanket assumption of incapacity under the guise of protecting the individual has resulted in their rights being threatened, with many being institutionalised against their will.

Challenges could arise if a person with an intellectual disability wishes to work or to reside in the community outside the residential service. In these circumstances, it may become the role of a social care worker to assist in advocating on behalf of the service user.

Dhanda (2013) believes in supporting the service user in the context of universal legal capacity as a universal human right through co-facilitation or joint decision-making. A large cohort of service users have wished to have more control over decisions which affect them, so much so that further amendments may be made to the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015 under ‘Deprivation of Liberty’, which is currently being proposed as an addition to Part 13 of the Act (DoH 2019: 4).

Another development in recent years was with the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2017 repealing a ban on people with intellectual disabilities having sexual intercourse. The 2017 Act allows for ‘protected persons’ being afforded the ability to consent, replacing the blanket ban prohibiting sexual activities outright that had been introduced by the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2003. Ní Aodha (2017) quotes Kathleen O’Meara of Rehab, who stated that it was an ‘important step forward in opening up the law around sexual relationships for people with disabilities’.

Social care workers can be faced with a variety of ethical considerations and the boundaries that must be in place to ensure the safety and wellbeing of the service user. For example, where a service user with an intellectual disability wishes to have sexual intercourse with another service user, how is this situation dealt with by the social care worker and the multidisciplinary team? There are so many questions that are raised by this scenario. This would be of particular importance if, for example, a couple were engaging in sexual intercourse and one of the parties withdrew consent during the act. Section 48 (9)(4) of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2017 states that ‘Consent to a sexual act may be withdrawn at any time before the act begins, or in the case of a continuing act, while the act is taking place’. From the moment that consent is withdrawn, and if the other party continues to engage in the act, the previous consensual act of intercourse becomes rape.

TASK 1

The movie Sanctuary tells the tale of a social care worker striving to do his best for his service user. Watch this film and make links to past and present legislation.

As well as the two groups set out above, some other categories of service users who may be affected by ‘lack of capacity’ legislation and guidelines/policies include those with mental health conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or who have suffered a substantial brain injury following an accident or stroke, and individuals whose capacity is diminished by brain disease conditions such as dementia.

The Mental Health Commission has introduced a Decision Support Service (available at https://decisionsupportservice.ie/), although at the time of writing it is not yet operational. The service will provide information on a variety of situations that may arise when working with a person with reduced capacity. Despite the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act being signed into law in Ireland in 2015 it is not yet fully operational. The HSE (2020) has provided a range of online aids to prepare staff within its remit of health and social care under a National Quality Improvement facility.

There are a number of actions people can take to safeguard themselves in the future should they become incapacitated. An enduring power of attorney (EPA) is a document lodged in court under which, if the donor (the person transferring the power) loses capacity to make decisions for themselves, they transfer decision-making powers to a nominated party or parties chosen by the donor. The attorney has the power under law to make decisions concerning the medical and financial welfare of the donor until their death.

Another option is for the person to create an advance healthcare directive (AHD), a document often described as a ‘living will’.

Specifically, this builds on person-centred planning, which is core to social care provision, to ensure a service user’s autonomy: service users will be afforded assistance in decision-making only when required.

The AHD will record a person’s wishes specifically in relation to decisions regarding their health should they become incapacitated in the future. Once the document is drafted to address the specific situation arising and executed while the person has full capacity and awareness of its meaning, it will have legal standing. The document can discuss a person’s wishes regarding medical treatment and end of life care, to include ‘do not resuscitate’ instructions, should such a situation arise in the future. The AHD will be a guide for healthcare providers and its contents can be revoked at any time by the service user. However, should the service user not have indicated their wish to revoke the document prior to its coming into force, its contents shall be valid. It should also be noted that the wishes contained in an AHD will override those contained in an EPA.

There has been much change in the area of social care provision over the past number of years. The one aim that is firmly in place is to safeguard the service user. Service users are now active participants, bringing to mind the term ‘nothing about us without us’, which can bring challenges in ensuring that their participation and choice will not cause them harm, and with the one goal of supporting their rights to the best of our ability.

Tips for Practice Educators

- Consider the points in the Venn diagram above.

- Always assume the service user has capacity to make the decision unless the opposite is proved.

- Ensure that you fully understand the intervention you intend to carry out with the service user and explain it to them in plain, easy-to-understand language.

- Remember that consent is an ongoing process. Approach each intervention as a new, separate task and support the service user to make the decision for themselves.

- Remember to document the approach you took as per your organisation’s policy in your service user’s care plan and carry out your ongoing health and safety risk assessment.

References

Age of Majority Act (1985). Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1985/act/2/enacted/en/ print.html> [accessed 1 January 2020].

Assisted Decision-Making Capacity Act (2015). Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2015/ act/64/section/3/enacted/en/html#sec3> [accessed 19 January 2020].

Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act (2017). Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2017/act/2/ enacted/en/print.html> [accessed 28 January 2020].

Charleton, M. (2007) Ethics for Social Care in Ireland: Philosophy and Practice. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 1993. Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1993/act/20/ enacted/en/print.html> [accessed 28 January 2020].

Degener, T. (2017) ‘Editor’s foreword’, International Journal of Law in Context 13(1): 1-5, doi:10.1017/ S1744552316000446.

DCYA (Department of Children and Youth Affairs) (2014) Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Dhanda, A. (2013) Universal Legal Capacity as a Universal Human Right. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Disability Act 2005. Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2005/act/14/enacted/en/print.html> [accessed 1 January 2020].

DoH (Department of Health) (2019) The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguard Proposals: Report on the Public Consultation. Dublin: DoH.

Finnerty, K. (2013) ‘Social Care Services for People with a Disability’ in P. Share and K. Lalor (eds), Applied Social Care. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Fyson, R. and Cromby, J. (2013) ‘Human Rights and Intellectual Disabilities in an Era of “Choice”’, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 57(12): 1164-72.

Hall, D.E., Prochazka, A.V. and Fink, A.S. (2012) ‘Informed consent for clinical treatment’, Canadian Medical Association Journal 184(5): 533-40. Available at <https://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/184/5/533. full.pdf> [accessed 19 January 2020].

HSE (Health Service Executive) (2018a) Discharge Policy. Dublin: CAMHS.

CAMHS (2018b) Parental Consent. Dublin: CAMHS.

HSE (2019) National Consent Policy. Dublin: HSE.

HSE (2020) National Quality Improvement – Assisted Decision Making, Available at https://www.hse.ie/ eng/about/who/qid/other-quality-improvement-programmes/assisteddecisionmaking/

Kinsella, M. and Harrison, N. (2016) ‘Best laid plans’, Law Society Gazette, November. Available at <https://www.lawsociety.ie/globalassets/documents/gazette/gazette-pdfs/gazette-2016/november-16- gazette.pdf#page=37>.

Larkin, M. (2009) Vulnerable Groups in Health and Social Care. London: Sage.

Lunacy Regulation (Ireland) Act (1871). Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1871/act/22/ enacted/en/print.html> [accessed 30 October 2020].

MCI (Medical Council of Ireland) (2008) Good Medical Practice in Seeking Informed Consent to Treatment. Dublin: MCI.

Mental Health Act (2001). Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2001/act/25/enacted/en/ print.html> [accessed 1 January 2020]

Ní Aodha, G (2017) [online] Decriminalisation of people with intellectual disabilities having sex welcomed, Available at https://www.thejournal.ie/people-with-disabilities-sex-law-3390227-May2017/

Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act (1997). Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/ eli/1997/act/26/enacted/en/print.html> [accessed 29 January 2020>.

Quill, E. (2004) Torts in Ireland (2nd ed). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Social Care Workers Registration Board Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics Bye-Law (2019). Available at <http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2019/si/52/made/en/print> [accessed 12 April 2020].

Sugarman, J., McCrory, D.C., Powell, D., Krasny, A., Adams, B., Ball, E. and Cassell, C. (1999) ‘Empirical research on informed consent’, Hastings Center Report 29(1):S1.

UN (United Nations) (1948) Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Available at <https://www.un.org/en/udhrbook/pdf/udhr_booklet_en_web.pdf> [accessed 28 January 2020].

United Nations. (1990). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available at https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx [Accessed 1 January 2020].

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available at https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html [Accessed 28 January 2020].