Chapter 18 – Iseult Paul (D1SOP18)

Domain 1 Standard of Proficiency 18

Be able to take responsibility for managing one’s own workload as appropriate

|

KEY TERMS Responsibility Workload management Time management Self-care |

Social care for me is … Supporting people with an intellectual disability, Teaching, training, cleaning, sometimes making the tea. Answering phones and writing reports, While doing my best to get right supports. It’s driving and trying out lots of new things and Holding a hand while someone gains their new wings. It’s walking and talking and learning about life, Then figuring out how to have ‘The Good Life’. It’s happy and sad, a bit scary at times and Sometimes things just get left aside. It’s parties and picnics and roof’s falling in, Distraction and Action, people never give in. It’s planning and dancing and singing a song, It’s knowing it’s okay when things do go wrong. Saying Yes, Saying No, knowing when to let go, And at the end of the day I get to go home. Poem by Iseult Paul

|

TASK 1

Make a list of all the responsibilities you currently have. Include personal and professional responsibilities as well as those of a student.

Now choose the five you think are the most important and number them 1-5 in order of importance.

Reflect on what guided you in making your decision.

Responsibility

Social care workers are responding to a regulated sector therefore it is important that they take responsibility for managing their own workload. The next section explores this in more detail. The good news is that there are some very simple tools and strategies we can use to help us manage our workload.

The level of responsibility we have at any given time can vary and is often influenced by a number of factors. The poem ‘Social Care for Me’ gives a brief insight into this. Social care workers practise across diverse environments, with different service user groups, and their work is often conducted in difficult circumstances. The section on managing time explores ways of using time more efficiently and effectively, while introducing you to the concept of multiplying time. Social care students, especially those with no prior experience, may have expectations that they will have considerably fewer responsibilities than those they work alongside. This may be the case initially, but as students progress through college and practice placements the level of responsibility will increase. Read Jenny’s story in the case study about how her supervisor’s expectation of her ability to take responsibility for a set task differed from Jenny’s ability to perform it. Different settings, management styles, the culture of the setting and the type of work can influence the level of responsibility given to students during placements.

There is a very long list of skills required by social care workers. Lalor and Doyle (2005:160) suggest that these skills can be categorised under five headings: Communication, Assessment, Planning, Intervention and Self-awareness. As our skills develop, so too do our responsibilities, and this can lead to stress. The section on self-care highlights the importance of self-care in social care and of creating a good work-life balance. As a social care student, you have a responsibility to show up to college, do the assignments set by your tutors, achieve the standard of education required by CORU and prove that you meet the 80 proficiencies set out in the standards (see https://www.coru.ie/files-education/scwrb-standards-of-proficiency-for-social-care-workers.pdf).

Responsibility is synonymous with accountability and can be associated with capability. For example, would you be responsible for performing tasks that you are not capable of? It would be lovely to be able to say that social care practitioners are not expected to perform tasks they are not capable of, but it would be remiss of me not to note that we are often asked or expected to perform tasks we feel or think we are not capable of.

TASK 2

Think about a time you were asked to do a task you felt you were not capable of doing.

How did it make you feel?

What could you have done differently?

Case Study 1

Jenny has been assigned the responsibility to make dinner for six residents, two staff and herself in a residential setting. Jenny’s placement supervisor assigned her this task based on the assumption that Jenny can cook, but didn’t actually ask Jenny if she could. Jenny has never cooked for a large group of people before and doesn’t feel her cooking skills are good enough to produce a meal for everyone. This is Jenny’s first placement and she hasn’t been on shift at dinner time before. She is worried that she will fail her placement if she doesn’t do a good job making the dinner.

What should Jenny do? Does she attempt to produce a meal for everyone, does she order food in and pretend she cooked it, does she say nothing and hope one of the other staff will do dinner, or does she discuss it with the other staff on duty?

In the end, Jenny discusses her concerns with the other staff members on duty, who reassure Jenny that they are there to support her, and as a team they come up with a simple solution. Jenny and one of the other staff members make the dinner together.

Sometimes in practice we learn by doing, and as a result we develop confidence in our knowledge and skills. Jenny learned by doing this activity with another member of staff, and the next time she was able to make the dinner independently. You may think the above scenario is unlikely to happen, but having to produce meals for individuals or groups of people, especially when it is your first time, can be scary – the last thing you want to do is poison everyone or appear incompetent. Learning how to cook is not on the curriculum for social care students but it is most definitely a skill required in some, if not all, social care settings. Tasks such as cooking or preparing a meal can provide opportunities to build relationships with staff or with service users, even if the cooking is not up to standard! As social care practitioners we have a responsibility to recognise and identify our own limits, and know when to seek advice from others (see Chapter 2 for more information).

TASK 3

Review a job description for a social care worker in a specific setting you are interested in, and look at the list of responsibilities. List the skills you already have that would enable you to take on some of these responsibilities.

Reflection and action planning can identify learning activities that help to build skills that lead to an increase in responsibilities (see Chapter 58, Domain 4-3). It is important to remember that you have a responsibility to show up and to conduct yourself in a professional manner in adherence to the social care code of conduct (see https://www.coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional- conduct-and-ethics-for-social-care-workers.pdf).

It is your responsibility to have a realistic experience from each of your placements. Discuss with your college tutor or placement supervisor if you feel you are not gaining enough practice or support to meet your proficiencies and develop your practice.

Managing Your Workload

As previously noted, as your level of responsibility grows, your workload also grows.

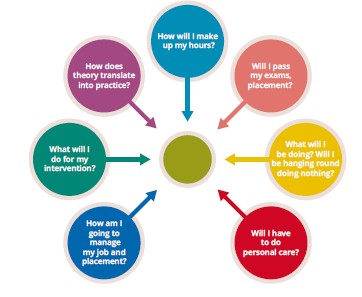

Students are often worried about what they need to achieve to pass their course and placement, such as:

How will I make up my hours? How does theory translate into practice? Will I pass my exams, placement? What will I do for my intervention? What will I be doing? Will Ibe hanging round doing nothing? How am I going to manage my job and placement? Will I have to do personal care?

Tip: Don’t panic! You have experience of managing your own workload

Students already have experience of managing their own workload, for example attending lectures, submitting assignments on time, managing college, work and their personal/social life. Practice placements differ according to the type of service provision and the environments in which social care work is conducted. Most students starting placements will have a settling-in period, and this is good practice, but this may not happen across all settings. A third-year student will have more experience than a first-year student, so supervisors and tutors will have higher expectations of them. Learning goals and pre-placement visits will provide valuable knowledge as to what students can expect from their specific placements and gain some understanding about their workload. Do your research on the specific setting.

As you progress through college and each of your placements your workload will increase, but there are a number of tools you can use to help you manage your workload effectively and efficiently. The To-Do list is popular, and can be created very easily either the old-fashioned way, with pen and paper, or using technology, such as an app on your mobile phone or computer. It is important not to have too many items on your To-Do list, so make a list for each day or shift. The important thing to remember is to use a system that works for you.

TASK 4

Make a To-Do list of all the tasks you need to complete.

[Today? This week?]

Once you have created your To-Do list, you need to review all the tasks on it and decide how you are going to prioritise them. The Eisenhower Matrix (see https://www.mindtools.com/al1e0k5/eisenhowers-urgentimportant-principle) is a useful framework that can help you prioritise tasks according to their importance and urgency. The matrix has four quadrants.

- Tasks in the first quadrant are both urgent and important and therefore have the highest priority. Tasks or decisions in this quadrant require immediate action and you must do them first.

- If a task is important but not urgent, it goes in the second quadrant – these are the tasks you can plan for. This is the quadrant we should try to manage most of our work in. (Planning is a core competency required for social care and when interviewing for jobs it is one of the competencies interviewees are asked to give examples of.)

- Tasks that are not important but urgent are those in the third quadrant, and these are the tasks you can delegate. Practice educators often delegate tasks to students on placement to free up their time so that they can focus on other tasks.

- Finally, in the fourth quadrant are the tasks, considered not important and not urgent. These tasks have the lowest priority and you might eliminate them from the To-Do list for that day or altogether. If they need to remain on the list, move them to the next day’s To-Do list.

In his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey expands on Eisenhower’s idea of what action needs to be taken when making decisions.

The Eisenhower Matrix

|

|

URGENT |

NOT URGENT |

|

IMPORTANT |

1. Both urgent and important Deadlines and crises (assignments, emergencies) Do |

2. Important but not urgent Long-term development (planned study, planning your time) Plan |

|

NOT IMPORTANT |

3. Urgent but not important Distractions with deadlines (some meetings, some emails/ calls) Delegate |

4. Not important and not urgent Frivolous distractions (frequently checking social media) Eliminate |

Source: adapted from Covey 1989

TASK 5

Using the matrix, place each task on your To-Do list into quadrants based on its level of importance and urgency.

This exercise can assist you in identifying how best to manage your workload by planning how to use your valuable time.

If you are spending most of your time in quadrant 1 on tasks that are important and urgent, you are failing to plan effectively. If you are spending too much time on tasks in quadrant 4, like checking your emails or messages every five minutes, you are probably wasting a lot of your time. Of course, checking and answering emails is part of our job, but it is less urgent and important than tasks such as ensuring someone is safe or has assistance with personal care. Tasks in quadrant 4 may never get done, or their level of importance may change – in which case, move them to a different quadrant. Set aside specific times for emails and phone calls where possible, and get rid of the tasks that will waste time, like surfing the net for hours on end. The most important thing to do is to review your To-Do list, check off tasks completed and add new ones.

Managing Time

Time management skills are one of our core competencies.

|

Statements often heard in a day service for people with intellectual disabilities. |

There aren’t enough hours in the day |

|

I have no admin time |

|

|

Where’s the time gone? |

|

|

Time flies |

|

|

I haven’t got the time to do it |

|

|

I ran out of time |

|

|

Where am I supposed to find the time to do that? |

|

|

I wish I had more time |

|

A conversation with a friend and her son led to some reflection and thinking about how we use our time. His mother had made a remark about time going slowly, which led to a discussion about how time actually moves. He said he didn’t understand why people said this kind of thing and made the point that ‘time does not go slow or fast, it moves at the same rate each time’. This led to a debate about how people might perceive time as going quickly or slowly. The following arguments were made:

- When we do something we enjoy, like going on holidays, or out with friends, time flies.

- When we do something we don’t enjoy, like housework, ironing, sitting in a hospital, time drags.

To test this theory we suggested that he went to put the kettle on, stand beside it and watch it boil, then come back and tell us if the time had dragged. He pointed out that this would be wasting time. He said, ‘I could be doing some press-ups while I wait for the kettle to boil and save time.’ His point was that it would take the kettle the same length of time to boil, whether or not he was watching it. So he would use this time in a more productive way – he was using his initiative to manage his time more effectively. Social care often requires us to be creative in how we use our time. Emptying the dishwasher while waiting for the kettle to boil is just one example; going for a walk or coffee with a service user and having a ‘conscious conversation’ is another. Gordana Biernat (2016) suggests six ground rules for conscious conversations (see https://www.powertalk.se/conscious- conversation/ for more information).

Good time management enables us to be more productive, and we often try to do more than one thing at a time, but does multitasking actually save time? In the above scenario you might think that my friend’s son was multi-tasking, but let’s take this a step further and consider the idea of him ‘multiplying’ his time.

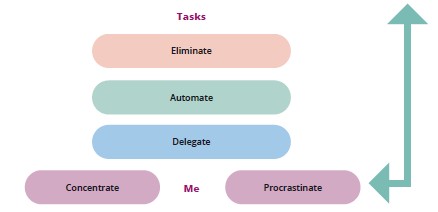

In his 2015 TED Talk, Rory Vaden, a self-discipline strategist and bestselling author, explores the idea of multiplying time (see https://youtu.be/y2X7c9TUQJ8). He suggests that people need to forget about trying to manage time and instead think about self-management. In introducing his concept of multiplying time, he makes the point that the ‘key to multiplying your time is to procrastinate on purpose’. When I was serving my apprenticeship in my previous profession, my mentor (who also happened to be my dad) always told me, ‘Don’t put off until tomorrow what you can do today.’ The concept of intentionally putting things off, and thus multiplying time, is intriguing. Time moves at the same pace – an hour is an hour no matter what – so how can we multiply it? It requires a different way of thinking, and involves looking at the significance of tasks. In order to multiply time, you must give yourself the ‘emotional permission to spend time on things today that will give you more time tomorrow’ (Vaden 2015). Vaden offers a framework called the Focus Funnel (see Figure 1), which is quick and easy to use, and I believe can serve us well in social care. He suggests that as tasks pass through the funnel the first question to ask is ‘Can the task be eliminated?’. One way of eliminating tasks is to say no to them in the first place. As social care practitioners we can struggle to say no, but we have to be realistic about what we can and cannot do, and know that it is sometimes okay to say no. Managing our workload effectively and efficiently often involves saying no to additional tasks or responsibilities. As practitioners we need to be flexible, and saying no might not be a viable option, but when we say yes to one thing we are indirectly saying no to something else.

When a task cannot be eliminated the next question is, ‘Can it be automated?’. Automating takes time but this is where spending time today can save time in the future, thus, multiplying your time. Vaden refers to this as ‘ROTI, Return on Time Invested’. Setting up databases, templates for risk assessments or for support plans, or draft email responses are examples of how this is done in practice. If a task cannot be automated, can it be delegated? We often spend a lot of time on tasks that we could have delegated to others; the reason we don’t delegate might be because we think that the other person cannot do the task or that we will do it better or more quickly. In his book Successful Time Management, Patrick Forsyth discusses the importance of investing time in order to save time. Spending time teaching others to do a task will save you time in the future, so think of it as a ROTI; or, in order to save time you must ‘Speculate to Accumulate’ (Forsyth 2019). Examples of this in social care might include teaching service users to do tasks independently, or teaching students how to run a specific activity or create support plans.

After each task has gone through the funnel and you have decided that it cannot be eliminated, automated or delegated, it drops out of the funnel. The only question left to answer is whether you should do it now or whether it can wait until later. If you must do the task now, you give yourself permission to ‘concentrate and focus’ on the task, free from other distractions. If you decide the task can be done later – what Vaden calls procrastinating on purpose – you ‘hold’ the task at the top of the funnel. At a later stage the task goes back through the funnel and this time it might be eliminated, automated, delegated or concentrated on. However, if the same task continues to be put off until later and constantly remains in a ‘holding’ position, then you should really have eliminated it, so be brave and take it off your To-Do list (Vaden 2015).

Figure 1: The Focus Funnel

Case Study 2

Ted (not his real name), a gentleman with an intellectual disability, asked that a staff member bring him to his brother’s and parents’ grave, which was close to his day service. Ted had been supported for a number of years by staff to go to the family grave on anniversaries. Ted travels to and from his day service independently and accesses his community independently and yet he required staff support to visit his parents’ grave. Ted’s key worker asked him why he needed a member of staff to go to the grave. Ted explained that he didn’t know how to get to the grave – ‘Staff always come with me.’ Ted also said he felt ‘angry’ with staff when they couldn’t bring him when he wanted to go. Ted also expressed his wish to be able to visit the grave more often to ‘keep it well’. This task has changed focus now and should be viewed as a goal for Ted to work on so he can go to the grave whenever he wants. Applying the Focus Funnel, this task is important; therefore it cannot be eliminated, it cannot be automated and at this early stage cannot be delegated. The result is that the key worker needed to concentrate and focus on this task and work with Ted towards a solution.

Ted and his key worker arranged to meet his other brother in the graveyard. Ted’s brother led the way, and the key worker took step-by-step photographs of the directions to the grave. She designed a visual support plan using the photographs and then she accompanied Ted to the graveyard to check that they could use it to find the grave, which they did. Spending time on automating the directions made them simple to follow. To check this out, a volunteer who had never accompanied Ted to the grave before went with him. Using the visual directions, they were successful in finding the grave. The next step was to eliminate the need for staff to go with Ted to the grave, which involved training Ted. This could not be automated, so delegating the task was explored with Ted, and then his key worker delegated the task of training Ted to a social care student on placement. Ted and the student went off with their visual support plan the first day, and were successful in finding the grave. Over her practice placement the student provided intense support training for Ted. Each time they went she reduced the number of prompts she gave him until she was not giving him any at all. To check that Ted was able to find the grave without any prompts she asked another student to accompany him and report back how it went and then focused on the steps that he was having difficulty with. Ted now goes to the grave independently, and sometimes his girlfriend accompanies him and they go for coffee afterwards. This has eliminated the need for staff support and has reduced Ted’s anxiety and his anger towards staff.

The staff, particularly Ted’s key worker, have multiplied time. They don’t have to spend time doing an activity they don’t need to or have to manage preventable behaviour incidents.

You might ask, ‘Why wasn’t Ted trained to do this task before?’ The importance/urgency matrix would say it was important but may have placed it at a lower level of urgency. Staff failed to plan ahead and the task only became urgent when Ted became angry. The Focus Funnel changes our thinking in terms of how significant a task is and this particular task had been put off for far too long. The task had not been eliminated from Ted’s To-Do list (so it was still on his key worker’s list of things to do); it was important to him. The problem was that staff were procrastinating because of the time required. A little bit of creativity, a partnership approach, and time spent concentrating on making a plan led to better outcomes, thereby multiplying time. Vaden (2015) speaks about how emotions such as guilt, worry, fear and anxiety influence or dictate how we spend most of our time.

This led to reflections about how social care workers spend their time. The very nature of the work can be emotional; for example, in the service I work in, we have experienced an unprecedented number of bereavements in a short space of time. Emotions impact on how we spend our time, especially during times of grief or stress, in both our personal and our professional lives. Priorities change in such circumstances and our number one priority is supporting our service users and colleagues. Do we go look at our To-Do List for that day and see if we can place this important aspect of our work onto it and assign it a priority level or number? The answer is no. We know in this instance, or in a crisis, what we need to do; and the reason why we know is because we feel it. We all know our service users are our top priority and supporting them becomes more important than our paperwork, phone calls, emails or housework.

The first time the unit I work in experienced a bereavement, it was unexpected. As a team, we were not only upset but unsure what we should do. We had many questions:

- How do we tell the men and women in our service their friend has passed away?

- How do we support them with their grief?

- Should we cancel our activities for the day?

- Who should we contact? Who do we need to inform?

- Can we go to the funeral? How can we get everyone there?

- Is anyone coming to support us?

We spent a lot of time trying to figure out what to do that morning and how best to do it. We couldn’t have planned for this particular event, but what we did do, as a team, was reflect on the experience and the likelihood of it happening again, and we created a ‘bereavement protocol’. Having this protocol in place means that we know what to do and how to do it, and we don’t waste time. We have multiplied our time.

Spending time with service users and building relationships is an important aspect of our job, and where students often think social care workers spend most of their time. Unfortunately, the reality is different, and a lot of time is taken up with admin tasks such as writing reports, answering or sending emails, making or receiving phone calls, creating risk assessments, doing the staff rosters, budgeting, attending meetings, doing housework and so on – the list is endless. In fact, a large portion of our time is spent working indirectly for or on behalf of service users.

TASK 6

Create a time diary and evaluate how you are spending your time.Tip: See https://www.businesstrainingcollege.com/business/what-is-a-time- diary.htm

Self-Care

The poem above gives some idea of what social care practice is like in a specific setting (intellectual disability). It highlights the various jobs that a social care worker does, from cleaning and making tea to spending time with people figuring out what supports they need or how they would like to live their life. The poem also demonstrates the flexibility required of the practitioner, and highlights some of the emotional aspects involved in the work we do. While each social care setting is different, the truth is that all practitioners have numerous responsibilities, an ever-increasing workload and many demands on their time. Creating To-Do lists, prioritising tasks, and effectively managing ourselves and our time are all strategies we can use to develop our practice, manage our workload and be more efficient. Regardless of the setting, social care work is demanding and emotional and it requires practitioners to be not only flexible but also able to cope with all the various demands on them.

Professor Tom Cox notes that stress can occur when ‘an individual perceives an imbalance between the demands placed on them on the one hand and their ability to cope on the other’ (HSA n.d.: 6). Social care practitioners do not have a physical box filled with tools to perform their work; they are the tool box. So we need to look after ourselves and develop self-care strategies. Self-care should be considered a core competency of the social care practitioner, and as a student it’s important that you start developing and practising this skill. You may already have some self-care strategies, for example going for walks, playing sport, taking time for yourself, doing activities that promote self-care such as yoga or mindfulness. If you do not have a self-care strategy it is advisable to develop one. Believe me when I say you are going to need it, and it will be one of the strongest tools in your toolbox. Self-care strategies do not have to be expensive or elaborate; in fact, some are cheap and easy.

The trick is to have a number of self-care activities that will help you create balance in your life and prevent or, in some cases, manage stress.

Remember, if you do not look after yourself, you will be in no position to look after anyone else. Give yourself permission to make yourself a priority, put it on your To-Do list and allocate the time you need to focus on your self-care activities.

TASK 7

Identify a number of self-care strategies for social care students/workers. Create a personal self-care plan and start using it.

Tip: see Tygielski (2019) at: https://www.mindful.org/why-you-need-a-self-care-plan/

Tips for Practice Educators

An essential requirement for achieving this proficiency is the student’s understanding of, and their ability to, manage their own workload. It is important for the student to recognise they will have different levels of responsibility based on their level of academic achievement and practical experience. It is also important to recognise that as an educator you have a responsibility to guide the student and ensure they are capable of managing the work and tasks that you assign during the placement. When your student makes contact to arrange a pre-placement visit, set aside the time to meet with them, give them a tour and an overview of the unit, introduce them to service users, and give them an idea of some of the tasks they will be expected to perform during placement. This is a good opportunity for you and the student to explore whether your particular setting is a right match for the student.

Instruct your student to look up the organisation’s website so they can develop an understanding of the service, its history, its service provision and the responsibilities of the social care worker. In my experience, the biggest concern that students have when they come into a placement is how to communicate with service users and what to do for their intervention. If you work in a setting that supports people with an intellectual disability, instruct the student to take the online course Communicating with People with Intellectual Disabilities”, which is available at the HSE’s online learning hub HSELanD (www.hseland.ie). If your setting is also a day service for people with intellectual disabilities, ask the student to complete the New Directions module. There are lots of free courses available from HSELanD website and some will be relevant to your particular setting.

Practice educators are often concerned about where they will find the time in an already busy schedule to supervise students. Consider the addition of a student or students to the team as an asset. Although you have agreed to supervise and support a student, service users are the ones accommodating them, so they should get something in return. As a practice educator, be creative, set specific tasks for the student that match their proficiencies and enhance the quality of service delivery. Consult with staff and service users for suggestions of work they would like the student to undertake. Examples might include: supporting and training service users to access their community; teaching and supporting service users to self-advocate; working with service users and key workers on aspects of person-centred plans and individual goals. Appreciate the difficulty for students to demonstrate initiative when they are starting a new placement. Planning on your part is essential. Design a specific timetable for students that will give structure to their day. Create a list of tasks students can work on during placement as this will reduce anxiety for the student, give focus for both of you, and the rest of the team will know what the student is working on.

Create an induction folder for your setting that includes relevant information, such as communication structures, policies and procedures and general information about how service is delivered. Maybe your student could create or contribute to one.

It is important that practice educators do not make assumptions that students can do specific tasks. Use supervision sessions to explore the strengths of the student, set realistic tasks and ensure they are managing their workload. Enlist the support of your colleagues, and have students shadow them in their duties.

Multiply your own time by setting aside time to teach students to do the practical aspects of the work, such as developing support plans, writing reports and facilitating activities. Think of this as return on time invested. Many students on placement have other commitments such as part-time jobs, families and college work. It is important that they recognise that, as their workload increases, they are at risk of experiencing stress. Encourage them to use a reflective diary and engage in self-care activities.As an educator it is vital that you recognise how you manage your own workload. As you will be leading by example, it is important that you demonstrate good practice in this proficiency. It is also important to ensure that your toolbox – you! – is in good working order. Self-care is important for you too, and if you are not already engaging in self-care activities, you should think of starting. Think of it as a preventive intervention for yourself. Let me finish this chapter by sharing with you one of the most valuable online courses I have come across in recent years. It is called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), it is easy to engage with, completely free and can be found at Palouse Mindfulness: https://palousemindfulness.com/.

References

Biernat, G. (2016) Six Ground Rules for a Conscious Conversation. Available at https://www.powertalk.se/ conscious-conversation/

Bouffard, W. (2013) Puttin’ Cologne on the Rickshaw: A Guide to Dysfunctional Management and the Evil Workplace Environments. Available at http://puttincologneontherickshaw.com/authors-blog/if-you-fail- to-plan-you-plan-to-fail/

Business Training College (2020) ‘What is a Time Diary?’ Available at https://www.businesstrainingcollege.com/business/what-is-a-time-diary.htm

Covey, S. (1989) The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. USA: FreePress. Forsyth, P. (2019) Successful Time Management. UK: Kogan Page.

HSA (Health and Safety Authority) (n.d.) Work-Related Stress: A Guide for Employers. Dublin. Available at: https://www.hsa.ie/eng/Publications_and_Forms/Publications/Occupational_Health/Work_ Related_Stress_A_Guide_for_Employers.pdf

Lalor, K. and Doyle, J. (2005) ‘The Social Care Practice Placement: A College Perspective’ in P. Share and N. McElwee (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Irish Students. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Mind Tools Content Team (website) ‘Eisenhower’s Urgent/Important Principle: Using Time Effectively, Not Just Efficiently’. <https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newHTE_91.htm>.

Mind Tools Content Team (website) ‘To-Do Lists: The Key to Efficiency’. <https://www.mindtools.com/ pages/article/newHTE_05.htm>

Rampton, J. (2018) Manipulate Time with These Powerful 20 Time Management Tips. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnrampton/2018/05/01/manipulate-time-with-these-powerful-20- time-management-tips/#f158a4357ab4

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at <https://coru.ie/files-education/scwrb-standards- of-proficiency-for-socialcare-workers.pdf>

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2019) Social Care Workers Registration Board code of professional conduct and ethics. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator. Available at https://coru.ie/files-codes-of-conduct/scwrb-code-of-professional-conduct-and-ethics-for- social-care-workers.pdf.

Tygielski, S. (2019) Why You Need a Self-Care Plan. Available at: https://www.mindful.org/why-you-need- a-self-care-plan/

Vaden, R. (2015) ‘How to Multiply Your Time’ (TEDTalk). Available on YouTube <https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=y2X7c9TUQJ8>

Useful Resources

HSELanD: the HSE’s online learning and development portal – www.hseland.ie

Palouse Mindfulness: Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) – https://palousemindfulness.com/