Chapter 35 – Natasha Davis-Dolan (D2SOP12)

Domain 2 Standard of Proficiency 12

Understand the need to work in partnership with service users, their relatives/carers (if appropriate) and other professionals in planning and evaluating goals and interventions, as part of care planning and be aware of the concepts of power and authority in relationships with service users.

|

KEY TERMS A partnership approach Key skills and qualities Social care in practice – case studies Power and authority

|

Social care is … the provision of professional care, protection and advocacy for and on behalf of vulnerable people and groups across the life span. Social care workers identify areas of need where support is required and implement solutions and interventions to address these needs. A partnership in social care involves two or more individuals or organisations working together towards a common goal or shared interest. |

Introduction

Social care workers are employed in a wide range of settings supporting children and adults who experience disadvantage, discrimination, social exclusion, prejudice, marginalisation and oppression. Working with children and young people in care and aftercare, I have experienced first-hand the importance of adopting a partnership approach with service users, with parents/carers and with other services. This proficiency highlights the importance of adopting this approach in order to meet the needs of service users. McArthur and Thompson (2011) advise that the effectiveness of family support work is dependent, in part, on working in partnership and applying a child and family-centred approach when addressing the needs of children and families. Fahlberg (2012: 239) stresses the need to establish a partnership with parents when it comes to decision-making as ‘no matter how scanty their knowledge, at the outset of case interventions and planning, the parents know more about their child than anyone else’, therefore, ‘for the sake of the child and the parents both, an alliance must be built with the family’. Research conducted by Gilligan (2019: 226) on the Irish foster care system reiterated the importance of working with service users, relatives and carers, confirming that a ‘stronger emphasis on person-centred work with children in care and their family members’ is required.

This chapter will focus on children and young people in care and aftercare and it will highlight the importance of and the relationships required to work in partnership and ultimately support the achievement of better outcomes for children and young people in care and aftercare. These relationships include the social care worker and the child or young person; the social care worker and the parents/ carers; and the social care worker and other professionals and services. The ability to build relationships and work in partnership in social care requires certain skills and qualities which are the building blocks to a mutually respectful and trusting relationship.

This chapter will focus on children and young people in care and aftercare and it will highlight the importance of and the relationships required to work in partnership and ultimately support the achievement of better outcomes for children and young people in care and aftercare. These relationships include the social care worker and the child or young person; the social care worker and the parents/ carers; and the social care worker and other professionals and services. The ability to build relationships and work in partnership in social care requires certain skills and qualities which are the building blocks to a mutually respectful and trusting relationship.

Building a partnership and the achievement of better outcomes is not without its challenges (Lalor & Share 2013: 252). However, equipped with the necessary skills and attitudes, the social care worker can successfully build a partnership. This chapter aims to promote awareness regarding the need for a partnership approach in social care and demonstrate, through the use of fictional case studies, how building partnerships is essential when working with these client groups. Three practical case studies are provided, upon which the student can examine, discuss, reflect upon and find solutions to best work through the underlying problem which acts as a barrier to the development of an effective partnership. Each case study, while not based on true events, are situations which can arise when working with children and young people in care.

The Partnership Approach in Social Care

The rights of children in Ireland are protected by:

- Child Care Act 1991

- Children First Act 2015

- Children First: National Guidance for the Protection and Welfare of Children

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Section 45 of the Child Care Act 1991 places a statutory obligation on Tusla, the Child and Family Agency, to make determination as to the support required for young people making the transition from care into aftercare. The Child Care Amendment Act 2015 requires that Tusla prepare an assessment of need and an accompanying plan for young people progressing to aftercare which identifies the needs of the young person and the supports required to achieve those needs (Tusla 2017). Child-centred planning, such as an aftercare plan, ensures that children and young people are heard and that the welfare and best interests of the child and young person are of the utmost importance. Access to parents is also the right of a child, reinforced by Article 9(3) of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In situations where a child is separated from a parent, such as when placed in the care of the state, the Convention provides for the child to have access to one or both parents. The Convention places obligations on state parties to ‘respect the right of the child who is separated from one or both parents to maintain personal relations and direct contact with both parents on a regular basis, except if it is contrary to the child’s best interests’.

In order to realise the rights of the child or young person, the social care worker and other professionals work in partnership with the child as part of a care planning process. This provides for the child’s voice to be heard in the decision-making. The Children First Act 2015 and Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures: The National Policy Framework for Children and Young People 2014-2020 (DCYA 2014), place certain obligations on those working with children to promote the achievement of the five national outcomes, which include safety. In order to achieve this outcome, Tusla (2015: 11) advises that:

‘Children and families are most likely to do well if they are provided with appropriate support in a timely fashion that is well coordinated, with good communication and partnership working between all professionals. From both a policy and practice perspective, partnership with families and between key agencies is essential. There is a need for on-going dialogue between parents, children and service providers to ensure that all those involved contribute to common solutions.’

TASK 1

Read Chapter 38 by Des Mooney for information on how professional

partnerships are achieved through inter-agency collaboration.

A need also exists to increase the child’s participation in care and care planning (Gilligan 2019: 224). There is anecdotal evidence that suggests that children in care and aftercare display characteristics such as anger and suspicion towards adults. This is indeed my own experience with children in care and highlights the necessity of a partnership between the social care worker and the child or young person. Lalor and Share (2013) suggest that building relationships with children and young people in care may prove challenging as the child or young person may have no previous experience of a trusting relationship. Therefore, the social care worker must work in partnership to support the child or young person through direct work, building trust to establish a safe place where the child or young person can feel comfortable and secure in expressing personal needs and goals. Parents whose children have been placed in care may experience displaced anger towards the social care worker and other professionals (Fahlberg 2012: 192). This anger, coupled with raw emotion and mistrust, can result initially in a volatile partnership that may take time to build, where the social care worker has to work harder to support the parent in building the confidence and capacity to parent well. Chapter 38 provides a detailed insight into professional partnerships through inter-agency collaboration resulting in better outcomes and will therefore not be discussed in detail here. The following table outlines the benefits of creating partnerships.

|

The Benefits of Working in Partnership when Evaluating Goals and Interventions |

|

A partnership builds trust where the voice of the child or young person is heard and both child and parental autonomy is respected. |

|

A partnership provides for a child-centred and family-focused approach. |

|

Working in partnership and encouraging participation in care planning and decision-making is shown to reduce anxiety and stress in both children entering care and their parents (Moran et al. 2016: 12). |

|

Building a partnership with service users, parents/family and other services can act as a protective factor which Moran et al. (2016) advise is ‘a person, process or system that helps to protect a young person from circumstances or risk factors that could adversely affect their quality of life or life chances’ and includes ‘both formal policy measures and programmes aimed at improving young people’s lives’. Biological family members such as grandparents and siblings, according to Moran et al. (2016), can provide a protective factor for children and young people in care and aftercare and help to support a smooth transition from aftercare to living independently. |

|

Partnership with other services and professionals promotes shared learning through interagency collaboration promoting increased efficiency in the delivery of support and service (McArthur & Thompson 2011). |

|

A partnership approach can empower parents to become better parents, supporting them to work through problems and find solutions. |

|

The inclusion of foster parents in care planning and a partnership approach regarding the child promotes positive fostering outcomes (Lietz et al. 2016), while Moran et al. (2016) advise that a collaborative approach which increases the participation of the child and all relevant adults in the care planning process can promote positive care experiences and better outcomes for the child. |

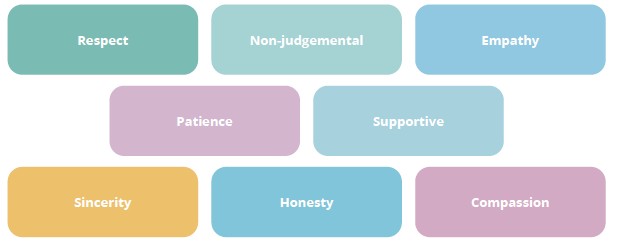

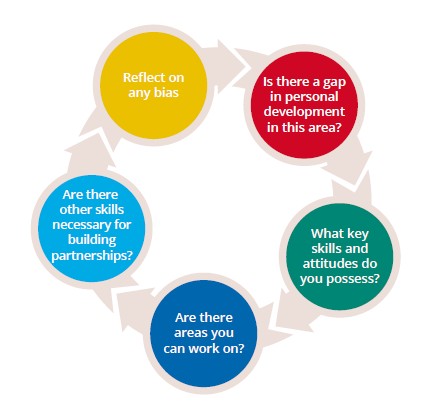

Key Skills and Attitudes Required for Quality Partnerships

TASK 2

Review the reflection guide below and write down the answers to the questions posed on the potential gaps in your knowledge, skills and personal development needed to build partnerships.

Social Care in Practice

These three case studies provide examples of a partnership approach to social care work.

Case Study 1

Maria

Week 1

Maria is a young mother who has two children, aged 3 and 5 years. The children were placed in foster care two months ago, due to neglect. Maria’s capacity to parent was seriously impacted by an addiction. Maria voluntarily entered into a rehabilitation programme for this addiction.

Supervised access for Maria and her children has been organised by the social work team. You are assigned to meet the foster parents with the children on the morning of access and then meet Maria at a local Tusla building for a 1.5 hour fully supervised access visit. The foster parents are quite anxious leaving the children. Mum arrives and is very excited to see the children, and they embrace. On entering the room in which the access is to take place, you observe many toys, blocks and colouring materials. Maria sits down and begins to talk to the children. The children appear to enjoy this time with Maria but are young and soon become bored. John, who is 3 years old, starts to cry and Billy (5 years) runs round and round the room in circles. Maria appears deflated and hands Billy her phone to look at cartoons. The children then sit watching the cartoons and do not engage any further with Maria despite her many attempts.

What can you as a social care worker do to enhance this valuable time for Maria, John and Billy?

How can you work in partnership with Maria to encourage her to become more involved and interactive with her children?

Is there a need to also work in partnership with the foster parents and the children?

What are the benefits of working in partnership for Maria, John and Billy and also for you, the access worker?

Week 2

The following week you ring Maria to discuss the upcoming access. You ask Maria if she would like to prepare an activity for the children to engage in. Maria does not respond. You

suggest some age-appropriate games and activities. However, Maria appears annoyed by each suggestion, stating they would not work with her children and that her children would not enjoy them.

What do you feel has caused Maria’s annoyance?

How can you support Maria’s autonomy as a parent?

Reflect on why parents whose children are in care may be reluctant to take on board suggestions and support offered by the social care worker and other professionals.

Suggest how you as a social care worker can build a partnership with Maria to ensure Maria and her children enjoy quality time together at each access.

Case Study 2

Kate

Kate has four children who are in foster care. You are briefed by the social worker on the case and advised that Kate can be inconsistent in her contact with the children. Therefore, the social worker feels it would be best if you made contact with Kate a number of times in the days preceding the access to ensure Kate has transport to and from the access and is aware of the time, duration and location. Access is arranged; however, Kate cancels on the morning of the access. Access is rearranged but Kate once again cancels due to illness. You speak with Kate and are assured by her that she has everything organised for a newly rescheduled access. You ring the foster parents and communicate the new arrangements. Kate is getting public transport,

so you ring on the morning of access to confirm she is on the train. Kate confirms she is on her way and will arrive 20 minutes before access. You confirm the arrangements with the foster parents, assuring them that Kate is on her way. The foster parents and Kate’s four children will have an hour-long journey to access and advise you that they will be leaving earlier to ensure the children have lunch before they meet with Kate. You are en route to the access when your phone rings and Kate advises that she boarded the wrong train and is now stranded with no connecting train to bring her to access on time. Kate states that she has forgotten her purse and that the next connecting train is later in the day. Kate is very upset at the possibility that she will not see the children and requests that the time of access is changed to later in the day. You are conscious that the foster parents and children are already en route but also that the social worker really needs this access to go ahead so that the children can spend time with Kate. You will be driving past the train station where Kate waits at the train station.

- Do you cancel access?

- What are the implications of doing so?

- Is there an alternative option?

- What are the implications of the alternative option?

- Can you see the need to work in partnership with Kate in order to ensure the children have regular and rewarding contact with her?

- Is there a need to work in partnership with the social worker also?

Kate’s case is a reminder of the very thin line between empowerment and enablement!

The social care worker has to make a quick decision: either cancel the access, resulting in more disappointment for the children, another wasted journey for the foster parents and a parent who you know would benefit from seeing her children; or discuss with the social worker and arrange to pick Kate up and bring her to access.

TASK 3

Discuss the following questions:

What choice would you make?

Is this choice enabling or empowering Kate?

What factors do you take into consideration?

How can you support and work in partnership with Kate to ensure this does not happen again?

Case Study 3

Case Study 3: Michael

Michael is 16 years old. He has recently been placed in an adolescent residential unit. Michael was initially placed in relative foster care; however, after a short time this placement broke down due to Michael’s challenging behaviour which included self-harm, substance misuse and overtly sexualised behaviour. You are asked to undertake direct work with Michael in order to support the achievement of Michael’s personal goals, which include a desire to gain part- time employment. You know that in order to do so, Michael will require support to express his emotions in a positive way. You have studied Michael’s case file and feel that all interventions to date have focused on the challenging behaviour and have not explored the underlying reasons for the behaviours that challenge.

- Is there a need to work in partnership with Michael as part of his care planning?

- How can a partnership between Michael and the social care worker support Michael to find alternative positive ways to express emotions?

- In developing interventions to best meet Michael’s needs and help him achieve his goals, is a partnership with other professionals important? Why?

- Is there a need for the case worker to work in partnership with other professionals and services in order to best support Michael?

Power and Authority

Social care work involves supporting service users, parents and families during times of need when emotions run high. The family, according to Clarke Orohoe (2014: 76) may feel powerless and unheard in interactions with support services. Research conducted by Gilligan (2019: 224-5) on foster care in Ireland reports that ‘for some parents there seems to be a general sense of losing influence or status’ plus a sense of exclusion from the child’s life heightened by ‘the lack of information they receive about what is happening in their children’s lives’. Social care work with children and young people in care and aftercare as described in Case Studies 1 and 2, highlights the power imbalance that some service users and parents/carers may find challenging. This negative perception of who holds the power or authority can also result in challenges for the social care worker who hopes to develop a partnership with the service user or parent. The involvement of service users, parents and carers in decision-making and care planning can provide for the sharing of power, thus promoting better outcomes. Person-centred planning respects the rights, feelings, thoughts and wishes of service users. This partnership approach to care planning empowers the service user, parents and family to participate meaningfully in decision-making and planning.

This proficiency raises the student’s awareness of power and authority dynamics in social care practice and encourages the development of a self-awareness regarding power in relationships with service users. The student is also encouraged to use the case studies to reflect on the ways in which a perception of power can negatively influence partnerships and how a partnership approach can alleviate negative perceptions of who holds the power or authority in the relationship.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

This proficiency enables students to understand the need for and importance of working in partnership with service users, carers and other professionals.

- Help students to apply theory to practice. Lalor and Share (2013) advise us that social care workers require a ‘thorough knowledge of procedures, policies and legislation’ and that it is this ‘theory base that gives them an understanding of people, systems and practices’. This theory base is achieved through study and examinations. However, this proficiency requires more than theory, aiming to support a practical understanding as to why a partnership benefits service users, parents/carers and professionals.

- Focus on skills of partnership work. Explore in supervision what skills and qualities the social care worker must possess in order to develop partnerships and why a partnership approach to care planning is essential.

- Design service-specific case studies. Interactive case studies can be utilised to encourage the student to explore and reflect on different areas of social care practice, and examine the need for and types of partnership in each area. The student can then relate theory to practice. Case studies can be supported by gaining the insight of other professionals or services on their partnership with the social care worker in a range of social care settings. This insight can demonstrate to the student just how important the partnership between the social care worker and the relevant other professional is and how the partnership can support the development of person-centred care planning and interventions to meet the needs of service users. Guest speakers can also increase the student’s awareness of the ways in which different services work in partnership with social care workers.

References

Clarke Orohoe, P. (2014) ‘The Language of Social Care’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons (eds), Social Care: Learning from Practice. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Corless, K., Horan, S., Kirkpatrick, B., Crocker, N., O’Donoghue, M. and Steiner, V. (2017) ‘The key attributes of a successful relationship with service users in family support: Views of family support workers’, Journal of Social Care 1(7): 1-6.

CORU (online) CORU Registration. Available at <https://socialcareireland.ie/coru-registration/> [accessed 3 August 2021].

DCYA (Department of Children and Youth Affairs) Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures: The National Policy Framework for Children and Young People 2014-2020. Dublin: DCYA. Available at <https://www.gov.ie/en/ publication/775847-better-outcomes-brighter-futures/>.

DCYA (2017) Children First: National Guidance for the Protection and Welfare of Children. Dublin: DCYA. Available at <https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/Children_First_National_Guidance_2017.pdf>

Fahlberg, V. I. (2012) A Child’s Journey Through Placement. London/Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

Gilligan, R. (2019) ‘The family foster care system in Ireland – advances and challenges’, Children and Youth Services Review 100: 221-8.

Lalor, K. and Share, P. (eds) (2013) Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill Education.

Lietz, C. A., Julien-Chinn, F. J., Geiger, J. M. and Hayes, PM. (2016) ‘Cultivating resilience in families who foster: Understanding how families cope and adapt over time’, Family Process 55(4): 660-72, doi: 10.1111/famp.12239 [accessed 1 August 2021].

McArthur, M. and Thompson, L. (2011) ‘Families’ views on a coordinated family support service’, Family Matters 89: 71-81.

McCormack, B., McCance, T., Bulley, C., Brown, D., McMillan, A. and Martin, S. (eds) (2021) Fundamentals of Person-Centred Healthcare Practice. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Moran, L., Devaney, C., McGregor, C. and Reddy, J. (2016) Scoping Review of International and Irish Literature on Outcomes for Permanence and Stability for Children in Care. Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, National University of Ireland, Galway.

Oireachtas (online) Bills and Acts of the Oireachtas <https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/bills/>.

Tusla (2015) The Prevention, Partnership, and Family Support Programme: Collaborative Leadership for Better Outcomes. Available at: <https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/PPFS_Low_Prevention_Services_ Brochure.pdf>.

Tusla (2017) National Aftercare Policy for Alternative Care. Available at <https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/ content/4248-TUSLA_National_Policy_for_Aftercare_v2.pdf> [accessed 21 April 2021].

UN (United Nations) (1990) Convention on the Rights of the Child. UN: Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR). Available at <https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc. aspx>.