Chapter 49 – Sheena O’Neill and Caroline Costello (D3SOP9)

Domain 3 Standard of Proficiency 9

Understand the need to monitor, evaluate and/or audit the quality of practice and be able to critically evaluate one’s own practice against evidence-based standards and implement improvements based on the findings of these audits and reviews.

|

KEY TERMS Qualityofpractice Evidence-based standards Monitoringand evaluation Implementation

|

Social care is … safe, effective, individualised and person-centred support to vulnerable and marginalised people to enhance their quality of life. |

Quality of Practice

Social care practice is dynamic, multidimensional and complex work. Social care workers are professional practitioners trained to provide safe, effective, individualised and person-centred support to vulnerable and marginalised people (SCI website) to enhance their quality of life. This support may be delivered over the short or long term. People who use social care services are entitled to high quality and purposeful care that meets the individual needs of the person (SCI website). This requires safe services and safe practices that take a person-centred approach to service provision while utilising best-practice approaches to provide quality care to people using services.

When we speak about best practice, it is sometimes assumed to be a commonly understood term, but, as we know, assumption of understanding can be dangerous. Best practice should not be considered as something we inherently know/understand but practice that has been developed from past failing, from knowledge (either evidence-informed or evidence-based) or from participatory approaches in care development.

In considering quality of practice, we must first have a clear understanding of the standards pertaining to our own practice. There are several stakeholders in the professional practice of social care, all with a multitude of roles and responsibilities. These stakeholders include: service users; social care workers; CORU; regulatory bodies; governance structures; and funding bodies. To ensure quality of practice it is important to consider each stakeholder’s participation:

Figure 1 Definition of quality in the Irish healthcare system (HSE 2016)

- Service user/person we support: The service user/person we support is the most important stakeholder and must be supported/facilitated by using appropriate models of participation and be given the opportunity to have an input into relevant reports, for example programme planning and HIQA audits. It is important to ask ourselves, if we never ask someone about their experience of receiving a support service, how will we know if it is right for them? If persons providing support become familiar in their social care role or ‘know’ what needs to be done, it can be easy to stop asking and start assuming. The service user has as much of an essential role in ensuring quality of practice as the person who uses the service. Each person using a service has a right to reliability, transparency and consistency, both in service delivery and practice approach, where their own responsibility is defined, as well as all parties involved in their support. This reinforces working in partnership and enables monitoring and evaluation to be a shared process. Working in partnership is critical to enabling and supporting the service user to be a participant in all parts of their plan of support, including monitoring and evaluation of quality of practice. The service user’s voice is vitally important as they will experience how the social care worker carries out their work, and they are directly impacted by it. It is critical that the service user’s voice and their feedback are captured.

- Social care workers: Social care workers must be guided by organisational and national policy and national legislation. They are bound by CORU’s Social Care Workers’ Registration Board Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics and must register with the professional body. Policies and procedures set out what is expected of the worker and provide guidelines to follow to ensure safe, equitable, consistent, and quality practice. Examples of policies that guide practitioner practice include child protection, safeguarding vulnerable adults, policy and procedure, behaviour management, risk management, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and health and Safety policy.

- Funding bodies: In Ireland social care provision is delivered through statutory bodies such as the Health Service Executive (HSE); Tusla, the Child and Family Agency; community and voluntary services such as youth services or family support projects; and private companies that run residential facilities for people of all ages. Where government funding is provided to non-statutory organisations there is a requirement to engage with providers via a memorandum of understanding (MOU) or service-level agreements. These funding agreements are built upon compliance with organisational and national policy, along with national legislation. Each of these policies is supported by evidence-based research and seeks to enhance public safety.

- Governance/regulatory bodies: These authority structures are established to verify that policies and processes are supported by evidence-based research and will enhance public safety. An example of this is CORU, Ireland’s multi-profession health regulator. CORU’s role is to ‘protect the public through regulating the health and social care professions listed in the Health and Social Care Professionals Act 2005 (as amended)’ (CORU website). CORU has a responsibility to safeguard the service user.

Evidenced-based Practice

Social care workers use evidence-based practice tools to enhance their practice. The Sicily Statement on Evidence-Based Practice (EVP) provides a commonly accepted definition: ‘Evidence-Based Practice requires that decisions about health care are based on the best available, current, valid and relevant evidence. These decisions should be made by those receiving care, informed by the tacit and explicit knowledge of those providing care, within the context of available resources’ (Leen et al. 2014). Evidence-based practices are supported by research and apply social care values and ethics to practice, and the processes prepare students to think critically about their approach to their work (Parrish 2018). These approaches have been validated through research carried out in the health and social care fields. Using an evidence-based approach in social care, such as the task-centred approach/crisis intervention/ person-centred approach (Lishman 2015), facilitates a clear pathway for working with people who use services. Evidence-based approaches provide a strategic and purposeful way of working to include areas such as assessment, planning and implementing a programme of care for service users. These clear planning pathways lead to monitoring and evaluation of work being delivered, the achievement of goals/ outcomes/plans, as well as the quality of practice of the social care worker.

Using evidence-based practice approaches gives transparency, accountability and responsibility to all stakeholders in the person’s plan of care and support. Additionally, it emphasises the need to evaluate the approaches used by the practitioner as well as the outcomes of the person at the centre of the care work (Parrish 2018). Stakeholders involved may include the person, family member, guardian, next of kin, social care worker, member of multidisciplinary team and the regulatory body (CORU).

FramingtheEvidence

The Framework for Improving Quality in Our Health Service (HSE 2016) shares six drivers for quality improvement in health and social care services, and points to organisational culture as being critical to continuous quality improvement (HSE 2020). Positive organisational cultures enhance positive outcomes (Braithwaite et al. 2017). The social care worker has influence is all aspects of the quality improvement framework, as can be seen in the following examples (HSE 2016):

- Leadership for quality: This requires committing to leadership strategies, and to seeking support and supervision for social care leaders. Within all levels in organisations there must be a common goal to seek to provide quality services. A meaningful focus on creating a positive culture within the organisation is essential. Mission statements and organisational values should not merely be something within a strategic plan, rather they should be embodied by all members of staff.

- Person and family engagement: This involves the service user and, where appropriate, family members in all aspects of person-centred care. Services must encourage, promote and develop strategies for participation, for example facilitating an appropriate and inclusive communication strategy. Advocacy groups play a vital role representing the interests of service users. Examples of advocacy groups include EPIC, an organisation that engages ‘with and for children and young adults who are currently in care or who have experience of being in care. This includes those in residential care, foster care, relative care, hostel, high support and special care units or facilities’ (EPIC website). Sage Advocacy is a support and advocacy service for vulnerable adults, older people and healthcare patients. When we speak about involving people in their care, we must demonstrate how this is facilitated. This may be achieved through a service user participation tool that is appropriate to the individual. It is equally essential to ensure that participation is meaningful. In youth work, the Lundy model of participation is used. This is a ‘rights-based model which conceptualises Article 12 by showing whatis needed to make young people’s participation in decision-making meaningful for the young person’ (Byrne & Seebach 2015: 10).

- Staff engagement: It is essential that practitioners participate in all staff engagement strategies such as supervision, decision-making/problem-solving, continuous professional development and positive mental wellbeing. Once again, we must consider what this will look like in practice. It is of little benefit for staff to engage in, and supervisors to conduct, performance management and development interviews if they are meaningless. For example, if a staff team request training they feel will enhance the quality of practice, and the manager agrees to provide it, but the training is not provided, or staff rostering does not facilitate staff attending the training, then this engagement is meaningless. Communities of practice are an important structure for social care sectors as they encourage peer support networks and sharing of good practice.

- Use of improvement methods: Examples include plan/do/study/act (PDSA), SMART goals (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and theoretically sound (evidence-based) or timed), the improvement method, and Lean Six Sigma. ‘Building measurement into all improvement initiatives is essential so that we know when improvements have occurred and when they have not’ (HSE 2016). It is essential that all steps in planning improvement measures are clearly captured/recorded, that timescales are established, and clear roles (who does what) are set out. It is essential to build in monitoring and evaluation strategies so that achievement can be measured, and changes made in a timely fashion where required. In addition, what is learned should be shared across the staff teams and any identified improvements implemented in a timely fashion.

- Measurement for quality: It is essential to collect and store relevant data, such as records, when working with service users to measure quality and progress; for example, the service user’s experience and achievement of all outcomes. This can, for example, be monitored at regular intervals throughout the implementation of a plan and evaluated at its conclusion. This data will inform improvements at a point in time and/or moving forward in your practice. The data gathered should be data that is purposeful, and in line with the requirements of the organisation. The burden of additional staff workloads will only be embraced by staff where the measurements are seen as more than a tick-box exercise, and there is a clear focus for improved outcomes. Plans/work practices must include clear measurement strategies: if we do not have clear indicators to measure quality of care, how will we know if this has been achieved?

- Governance for quality: Social care workers ensure that they work in line with policies and procedures to ensure that their work is safe, effective and person-centred, and that they are accountable. Remember, policies and procedures are living documents and can always be developed and refined to ensure that the quality of care and the safety of all stakeholders is enshrined.

Social care workers play a key role in designing programmes of support and care that are individual to the needs of the person using their particular service, e.g., a support plan for a person with a mental health difficulty or intellectual disability, a risk management plan for an older person, an education/ employment plan for a young person, after-care planning for a young person leaving care.

How a social care worker carries out their work has huge significance in the development, experience and outcomes of the service user. Work carried out with service users should have clear purpose and process to determine the best course of action for outcome achievement. It is important to set clear aims and objectives so that the service user is clearly understands what the expectation is and why.

In our experience many of the pieces of work facilitated by social care workers are not apparent to a non-professional observer. For example, the relationship-building component of engaging with a service user is the foundation to identifying the service user’s support needs. Sometimes this relationship building may begin with a cup of tea, but this is only the first step in a clear process with an identified purpose as the end goal. What is unseen is the assessment that is being undertaken by the social care practitioner and the building of a relationship that is necessary to facilitate the enhancement of quality of life. If our focus and role as social care workers is not clear, it causes confusion for all stakeholders. ‘Knowing as we go’ in social care is unlikely to be purposeful and could create a dependency for sustained support among service users and families. Part of professional practice is to be transparent in terms of what practice is being undertaken and why. In this way it is important to follow the social care process to build the helping relationship using models such as the ASPIRE (assessment, planning, intervention, review and evaluation) model (Sutton 2006).

Monitoring and Evaluation

Best practice identifies that social care work must be delivered in collaboration with the service user, as their voice and wants are an integral part of the process. Assumption of a ‘quality practice’ being provided is not enough. Research has shown that effective and efficient practice requires monitoring and evaluation. Quality of practice and quality care requires a commitment to quality improvement. The pursuit of quality practice should be for ever evolving as workers strive for excellence. There are many examples of best practice and outcomes achieved with success. Unfortunately, there are also examples of service users’ interests and safety not being prioritised, where adequate quality assurance processes were not in place and/or not utilised. This has resulted in wilful or circumstantial neglect/ abuse of service users and where legislation such as whistleblowing and protected disclosures were invoked to remedy these failings.

‘To audit for quality improvement requires a systematic review and evaluation of current practice against research-based standards with a view to improving clinical care for service users’ (HSE 2016).

Monitoring and evaluation are essential components of quality improvement. Their purpose, in the most basic sense, is to seek what works, what does not work, and what improvements can be made for immediate implementation and forward planning. If you consider the quality improvement framework provided earlier, monitoring and evaluation should take place for each individual driver. This process of monitoring and evaluation is central to auditing practice with a view to improving both the service and service user experience (HSE 2016).

Planning with evaluation in mind helps to develop strategy in a focused and measured way. It also provides clarity to the social care worker’s role in supporting the service user, and how they will go about their work. Monitoring promotes corrective action in a timely manner, taking account of what is not working and/or hindering progress. Planning one’s own engagement practices throughout the body of social care work is equally essential for continuous professional development. As social care workers we know that our journey of education does not end when we graduate from our programme of study. This is our grounding in theory and application to practice. As a professional practitioner, each social care worker has a responsibility to engage in critical reflective practice to review their own practice and its effectiveness and impact. As we develop as practitioners and in a soon-to-be regulated profession, completing and maintaining a continuing professional development (CPD) portfolio is essential. We need to be available for training appropriate to our role which will enhance the quality of care we provide, as well as our capacity to care. Maintaining our CPD portfolio allows us to reflect on the new knowledge we have gained and enables us to plan how it will be integrated into our professional practice.

Evaluating one’s own practice can be considered through a vision of co-production (SCIE 2020). At its core, co-production is a partnership approach to working with service users where the service user has input into all aspects of decision-making. Co-production elicits a collaborative working approach requiring the social care professional and the person using the service working as equals sharing power as they work toward identified goals. Co-production is intrinsic to good-quality practice. It speaks to the ‘Nothing about me without me’ approach to care. The front-line worker is a tool for change in a service user’s life, and their voice should not take precedence. It is important to note that a social care worker’s professional tools are not always obvious, so we must use opportunities such as self-care strategies, reflective practice and CPD to reboot and replenish.

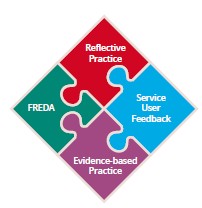

We are required as practitioners to frequently monitor and evaluate personal practice; to identify and acknowledge good practice for its continued implementation, and knowledge gaps that have impacted care of the service users so that other resources and/or training and supervision can be sought; and to make timely changes. For quality assurance and a person-centred approach, the FREDA principles of human rights (fairness, respect, equality, dignity and autonomy) can be utilised as a focal point for monitoring and evaluation. The FREDA framework takes a rights-based approach to supporting people (HIQA 2019).

As previously addressed, best practice in social care work is underpinned by evidence-based and evidence-informed practice approaches. While experienced social care workers develop expertise in their roles, which naturally develops confidence, this can result in complacency within the role. Where this occurs, the structure of monitoring and evaluating practice can be under-prioritised and prevents practitioners asking questions such as Why are we doing this? or How could we enhance our practice? It is essential that all social care workers are aware of what is best practice for the sector that they are working in so that they can work in a way that best supports the service user and that is transparent and equitable. This supports consistency among the staff in responding to service user need. Where there is an absence of understanding of evidence-based practice this can lead to difficulty with providing best practice as well as adequate and appropriate service provision to the service user.

TASK 1

Describe an activity that makes you feel good. Write down your role in that activity and any contribution from another person. Now write down how youfeel you could make it better.

For example, I really enjoy having a coffee in a fancy café. My role is to walk in, order my coffee and special extras such as a shot of syrup or oat milk. I usually meet a friendly barista who asks what my preferences are and tailors my coffee for me. They have listened to me and then provide this service. Sometimes I feel it may be too sweet and I know it is because I have not communicated my preferences such as a half shot of syrup, etc. The experience would be better if I communicated this preference, but I sometimes forget and would appreciate it if I had a choice about the quantity of the ingredients. I also feel that people are busy and forget to personalise the experience.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

For students to achieve this standard of proficiency they must have a clear understanding of the importance of critiquing their own practice, and why they should do it. It is important that the student understands the sequential pathway:

- How it is guided

- Whose voice is most important and

- What their role is.

- It is important that the student can see that any plan, intervention or outcome-based activity is not complete without evaluation and will not meet its full potential in the absence of monitoring. Even the best-laid plans, if unaudited, can go wrong.

- Speak to your student about their role in a service user’s life. Give them the FREDA human rights framework when they are preparing a piece of work with a service user and ask them to keep it in mind as they progress through any plan they make with a service user.

- Get the student to ask the service user how they feel they could be best supported by them.

- It is important for the student to work with the service user in all aspects of planning and monitoring. Co-production requires effort and investment and marries well with quality practice.

- Discuss co-production with your student as an auditing tool for their practice. The student will be required to demonstrate service user involvement at all planning and delivery points. It is vital that the students can see that their role is not to make decisions for the person, and that to ensure quality they must take a partnership approach.

- Students must show a methodical and evidence-based approach to their work.

- Students must be aware of the standards guiding their practice in the sector they are engaged in. in. Ask your student to research the governing standards of your organisation and get them to identify one theme/standard. Get them to take some time to evaluate the current practice of the organisation and create some recommendations under their identified theme/standard. An example of a governing standard might be from HIQA, HSE or Tusla. This could be used to feed into a team meeting.

- An important question to consider with your student is: Does effective input ultimately lead to effective outcomes? No – the dynamic nature of working with people means that results will not always be as desired. Choosing a practice approach to facilitate growth and achievement is only a part of the work journey for a social care worker; monitoring and evaluating are essential to checking whether the chosen approach is working. In fact, an intervention may produce vastly different outcomes to what has been anticipated. As we cannot always predict how things might go, monitoring and evaluation must be planned and transparent. This too is true for taking responsibility to audit one’s own professional practice. It demonstrates professional accountability. A social care worker and service user cannot always anticipate how things will proceed, and adaptation may be required to achieve success or the best possible outcome, in a timely manner.

Bibliography

Braithwaite, J., Herkes, J., Ludlow, K. et al. (2017) ‘Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: Systematic review’, BMJ Open 2017.7: e017708. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017708.

Byrne, S. and Seebach, M. (2015) Youth Participation Policy: A Federal Policy for Whole Organisation Change [ebook]. Youth Work Ireland. Available at <https://www.youthworkireland.ie/images/uploads/ general/Youth_Work_Ireland_Participation_Policy_Fina.pdf> [accessed 1 February 2021].

CORU (website) ‘What Is CORU?’ <https://www.coru.ie/about-us/what-is-coru/>.

DCYA (Department of Children and Youth Affairs) (2015) National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation In Decision-Making 2015-2020. Available at <https://assets.gov. ie/24462/48a6f98a921446ad85829585389e57de.pdf> [accessed 10 May 2020].

EPIC (Empowering People in Care) (2012) ‘My Voice has to be Heard’: Research on Outcomes for Young People Leaving Care in North Dublin. Available at <https://www.epiconline.ie/wp-content/ uploads/2020/04/My-Voice-has-to-be-Heard-EPIC-report-1.pdf> [accessed 25 May 2020].

(website) About Us. Available at: <https://www.epiconline.ie/about-epic/> [accessed 22 March 2021].

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2012) National Standards for Safer, Better Healthcare. Available at: <https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2017-01/Safer-Better-Healthcare-Guide.pdf> [accessed 3 May 2020].

Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) (2019) Guidance on a Human Rights-Based Approach in Health and Social Care Services. Available at: https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2019-11/Human-Rights-Based-Approach-Guide.PDF (Accessed: 4 May 2020).

Health Service Executive (HSE) (2016) Framework for Improving Quality in Our Health Service. Available at <https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/qid/framework-for-quality-improvement/framework-for- improving-quality-2016.pdf> [accessed 2 May 2020].

Health Service Executive (HSE) (2020) By all, with all, for all: A strategic approach to improving quality 2020-2024. Available at: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/qid/strategic-plan-2019-2024/strategic-approach-2020-2024.pdf (Accessed: 2 May 2020).

Leen, B., Bell, M. and Patricia, M. (2014) Evidence-based Practice: A Practice Manual [ebook]. Kilkenny: HSE. Available at <http://hdl.handle.net/10147/317326> [accessed 19 May 2020].

Lishman, J. (2015) Handbook for Practice Learning in Social Work and Social Care: Knowledge and Theory. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Parrish, D. (2018) ‘Evidence-based practice: A common definition matters’, Journal of Social Work Education 54(3): 407-11.

Proctor, E. and Khinduka, S. (2017) ‘The pursuit of quality for social work practice: Three generations and counting. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 8(3): 335-53.

SCI (Social Care Ireland) (website) <https://socialcareireland.ie/> [accessed 2 May 2020].

SCIE (Social Care Institute for Excellence) (2015) Co-production in Social Care: What it is. Available at: <https://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/guide51/files/guide51-easyread.pdf> [accessed 10 May 2020].

Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) (2020) Co-production in social care: What it is and how to do it. Available at: https://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/guide51/practice-examples/you-in-mind.asp (Accessed: 5 May 2020).

Sutton, C. (2006) Helping Families with Troubled Children. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Youth Work Ireland (2015). Youth Work Participation Policy: A Federal Policy for Whole Organisational Change. Available at <https://www.youthworkireland.ie/images/uploads/general/Youth_Work_Ireland_ Participation_Policy_Fina.pdf> [accessed 10 May 2020]