Chapter 59 – Caroline Coyle and Imelda Rea (D4SOP4)

Domain 4 Standard of Proficiency 4

Understand and recognise the impact of personal values and life experience on professional practice and be able to manage this impact appropriately.

|

KEY TERMS Understanding Recognising Impact of personal values Impact of life experience Professional practice Managing impact appropriately

|

Social care is … the creative engagement of relationality as a therapeutic working medium used within the life space of an individual or family; to communicate, inspire, guide, support, advocate for, and empower that person or family to realise their potential in their unique life journey. |

TASK 1

Consider a time when your personal values and/or life experience impacted on your professional practice. Describe how you managed this impact.

Understanding and Recognising Personal Values and Life Experience

Our personal values shape the way we negotiate our pathways through life. They provide a contextualised framework interwoven with our unique understandings, viewpoints, morals and beliefs. Our life experience and personal values influence the choices we make in our life journey, how we relate to, and construct our relationships with others and how we view, comprehend and make decisions. Once we understand the threshold concept that our personal values can consciously and subconsciously powerfully influence and impact each of our relational experiences, then we can explicitly recognise how our personal values and beliefs affect our daily decisions and behaviour, in everyday life, work, education and professional practice (Cousin 2006).

By understanding and recognising our personal values and beliefs, and knowing the impact of our personal values and life experience, we can prepare and plan to manage the impact when we encounter values and/or beliefs that are different from or jar with ours in our professional practice as social care practitioners. Attributed to the philosopher Socrates is the saying, ‘To know yourself is the beginning of all wisdom’, and what we know about ourselves, how we know it and how, as a result of knowing, we can instinctively ‘nod to this acknowledgement of knowing oneself’ in our everyday personal and professional relationships is the foundation of effective social care practice. Fenton highlights the paramountcy of self-awareness in social care work, stating ‘Our epistemological position (typologies of knowledge-what we know and how we know it) is a valuable insight for each practitioner to be aware of as it is we ourselves that are our most valuable tool in working with young people’ (2019: 42). Lyons, in her earlier work on self-development in the social care context, notes that ‘Central to the student’s ability to develop as a competent practitioner, is their knowledge of self, and how their upbringing, experiences, values and beliefs affect their ability to work with vulnerable people’ (2007: 1). By developing an awareness of self, one gains a heightened intuitiveness of the internal and external working versions of self. This personal self-development lends itself to internalising how our complex selves can impact the authenticity, quality and effectiveness of the relationality between us as the social care worker and the people we support; the relational space between the carer and the person being cared for.

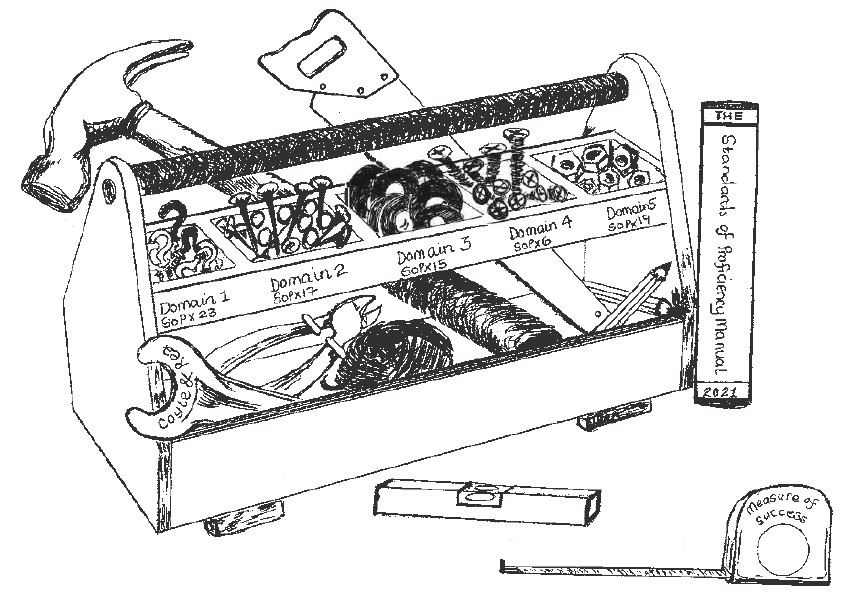

SCWRB – Standards of Proficiency Toolbox (Illustration by Rea 2021).

With regard to SCWRB’s standards of proficiency, it may be helpful to visualise the Standards of Proficiency (SOPs) as being represented by a ‘toolbox of social care skills and knowledge’ with each of the proficiencies being a tool which students can aim to acquire, practise and develop on their academic and practice placement journey. Subsequently, graduates are required to possess the complete toolbox of social care skills and knowledge to gain access entry on the social care register. Any skilled craftsperson will attest to the fact that using the correct tool/s (one which is fit for purpose) makes all the difference to the end result. Regularly caring for and maintaining the tools of your trade is essential, as is embracing new tools, techniques and training with which to elevate one’s skill level.

One of the tools required of graduates under Domain 4 Professional Development is to understand and recognise the impact of their personal values and life experience on their professional practice and to be able to manage this impact. Our values, attitudes and life experiences provide a template for how we develop and interpret relationships with others as we navigate through life.

Values: Our personal values are the degree of importance we attribute to certain beliefs, which motivates us, directs us in our ethical behaviour and guides the way we live our life. As individuals we may have shared and different values, e.g., being kind, advocating for others, being honest and valuing family and community. External influences, such as generational, cultural and/or religious factors, may impact on how we prioritise these values.

‘Values are attitudes or feelings about the worth of people, objects or activities. Individual values can be conflictual, and are contained within a value system, the adopted set of values influenced by culture, family, religion and society’ (Lyons 2007: 14).

Attitudes: In practice, the term ‘attitude’ is often used as an umbrella expression covering such concepts as preferences, feelings, emotions, beliefs, expectations, judgements, appraisals, values, principles, opinions, and intentions (Bagozzi 1994a; 1994b, cited in Jain 2012: 2). Our attitudes are constructed psychologically in relation to our values and beliefs; how we think about, evaluate and feel about things, people, places, experiences. According to Jung (1971), attitude is a ‘readiness of the psyche to act or react in a certain way’. Our attitudes directly influence our behaviour and can change as the result of our experiences.

Our life experiences: Our life experiences shape our identity and impact on how we live our lives. What we experienced and how we remember past experiences, what learning, if any, arose from those experiences, and how experiences can trigger emotions have the potential to govern our future interactions across the life course. Developing self-awareness of one’s own identity entails reflecting on the knowledge of one’s cultural background and heritage, including but not limited to one’s race, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, biases and prejudices.

Race: Ireland, once a homogenous nation, is now a multicultural society with people of many different nationalities making their home here. In social care, it is important to familiarise oneself with cultural competence and the cultural competence self-assessment questionnaire (Mason 1993). ‘The Census 2016 Profile 7 Migration and Diversity report shows that the 535,475 non-Irish nationals living in Ireland in April 2016 came from 200 different nations. Polish nationals were the largest group with 122,515 persons followed by 103,113 UK nationals and 36,552 Lithuanians. Just twelve nations each with over 10,000 residents – America, Brazil, France, Germany, India, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Spain and the UK – accounted for 73.6% of the total non-Irish national population’ (CSO: online).

Gender: Globally throughout history certain groups in society have been discriminated against on religious, legislative, political and social policy grounds, which in turn have been used to reinforce structural inequalities. Notably in Ireland, with its unique historical and cultural intertwining of State and Church patriarchal governance and control, women have been discriminated against. In their book Producing Knowledge, Reproducing Gender, Corcoran and Cullen identify the broader historical factors which determined gender inequality in Ireland, highlighting the revelations that have surfaced in the past few decades:

‘In contemporary Ireland gender equality and claims for women’s interests have featured in a series of public issues that have exercised the media, political elites, and public opinion. These include, waves of revelations about the fate of unwed mothers and babies subjected to state and church control; women’s rights and access to reproductive health care; sexual harassment and assault specifically within the cultural and creative industries; and the legal system’s approach to rape allegations’ (2020: xvii).

Sexual orientation: The impact of shared values is powerful. For example, the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act passed through the Oireachtas on 24 June 1993, decriminalising homosexuality and leading the way for a more open and inclusive society. The people of Ireland have pushed for greater change and acceptance in society for LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual) people, leading to the 2015 referendum on same-sex marriage rights, which passed into law in November of the same year. The popular vote enabled Ireland to become the first country in the world to extend marriage equality to same-sex couples by popular vote.

Socioeconomic status: Socioeconomic factors such as occupation, education, income and housing affect the way we live our lives. Unemployment, ill health, lack of adequate education and housing are strong indicators of health and wellbeing in later life (Bronfenbrenner 1979). According to the Healthy Ireland: Framework for Improved Health and Wellbeing 2013-2025:

‘Health and wellbeing are affected by all aspects of a person’s life; economic status, education, housing, the physical environment in which people live and work. Health and wellbeing are also affected by policy decisions taken by Government, the individual choices people make about how they live, and the participation of people in their communities.’ (Government of Ireland n.d.)

Ethnicity: For decades in Ireland research has evidenced active political and societal discrimination against Travellers (Mac Laughlin 1999). Every aspect of Travellers being othered in Irish society, from accommodation to education, has been well documented. Various attempts to assimilate the Traveller minority illustrated resistance to accept Travellers as culturally distinct with their own ethnic identity. One of the major changes in Irish history was in 2017 when the Irish government recognised Travellers’ ethnic identity.

‘Our Traveller community is an integral part of our society for over a millennium, with their own distinct identity – a people within our people … As Taoiseach I wish to now formally recognise Travellers as a distinct ethnic group within the Irish nation. It is a historic day for our Travellers and a proud day for Ireland.’ (An Taoiseach Enda Kenny, 1 March 2017, Pavee Point n.d.)

This recognition brought with it the call for organisations, large and small, to address their values systems. The beginnings of a ripple effect is evident. In education alone, the first national access plan (Achieving Equity of Access to Higher Education in Ireland 2005-2007) identified Travellers as a specific group to be prioritised and included in successive plans. A National Action Plan for increasing Traveller participation in higher education was launched in 2019. Despite legislative and policy developments in recent years, many Travellers still experience racism, health inequality, marginalisation and discrimination based on the values and beliefs of a few, all of which impacts on opportunities to progress at the same level as their settled counterparts (Omidi 2019; McGinnity et al. 2017). Reflecting on the knowledge of one’s cultural background, heritage and intersectionalities helps us to gain an understanding of how these intersections of self give rise to one’s attitudes and values, and consequently make up our unique, multifaceted, complex identity of self. Once there is recognition and understanding of self, we can begin to process, understand and manage our bias.

Bias and prejudices: Bias is a prejudicial unfair inclination against a certain person, belief or group. In Wahler’s study ‘Challenging social work students’ bias’, she notes that:

‘All students have individual bias, that can affect their judgment and ability to utilise professional values when interacting with marginalised groups in social work practice. While traditional cultural diversity courses often address racial, ethnic or sexual minorities, many students are biased against other groups that may not be included’ (2012: 1058).

As a social care worker, it is vital to reflect and consider one’s bias and prejudices. You may be working with certain groups in society (apart from racial, ethnic or sexual minorities) such as substance misusers, alcoholics and addicts; domestic violence victims; people with mental health challenges such as schizophrenia, bipolar and borderline personality disorder. Johari’s window, a graphic model which is used to help people to understand their own self-awareness, and their relationships with their self and with others, would be helpful here in realising what is known and unknown to self and what is known and unknown about self to others (Luft & Ingham 1955).

How do we know we are biased? Wahler’s (2012) study proposed a four-step teaching methodology to help students self-identify and challenge their own biases and prejudices:

- Consciousness-raising

- Identification of the target group

- Education and exposure of the targeted group

- Self-reflection.

Classroom groupwork and individual exercises may be undertaken in order to raise consciousness of the group or groups against whom the students have the strongest bias. In commencing consciousness-raising of a group, students are asked to identify a group or groups in society that they are uncomfortable or frightened of working with. Once the groups are identified, students then participate in writing exercises on the reasons why the particular groups were chosen. Through class discussion and debates, stereotypes and assumptions about the group are explored, and, hopefully, as in the findings from Wahler’s study, challenged. As part of the first step of consciousness-raising, students are also asked to prepare a ‘brief, out of class self-reflective assignment to explore their family of origin, and peer groups values, beliefs and stereotypes regarding the targeted group and note any differences or similarities between their social circle idea of the group and their own’ (2012: 1063-4).

This exercise allows the student to reflect on the different influences which may affect their own bias. Researching, gathering, disseminating, sharing and presenting information about the targeted group in relation to oppression, discrimination, stigmatisation and social injustices provides an opportunity for other students to see and understand the impact of bio-psychosocial factors and determinants. One way in which this information may also be captured is in an interview with a social care worker who is already working with the targeted group, to gather their opinions about societal stigmatisations towards the group. (Wahler offers detailed questions for this interview (2012: 1066).) Self-reflection exercises and written work are vital throughout the different steps of challenging your own bias and prejudice process. Writing in a reflective diary or journal is conducive to processing, negotiating and making sense of your individual thoughts and feelings. According to Wahler (2012:1067), ‘Previous studies have suggested that exposure to and engagement with different types of individuals can reduce bias and prejudice (Comerford 2003; Swank & Raiz 2007; Eack & Newell 2008; Chonody et al. 2009)’.

Meeting, talking with, visiting and interacting with members of the targeted group can help the students see, hear, gather information and learn from another perspective. Space and time are then made for class reflections on changes that may have occurred as a result of, e.g., hearing members of the targeted group talk; or a realisation of one’s own familial influence; or gathering evidential research into the relationship between oppression and the targeted group. When we understand our own bias and prejudice, we can know ourselves, we have the ability to acknowledge the potential for bias within us. As findings from Wahler’s study conclude, ‘Once students are aware of bias, understand issues affecting particular groups more fully, recognise effects of injustice and oppression and experience stories or relationships with people in the targeted group, beliefs can change’ (2012: 1068-9).

The ability to recognise the effects of oppression, injustice and bias is a developmental process in our academic and life journey. Consistent self-reflection and self-reflexivity enable us to be honest with oneself in acknowledging personal bias. According to Bolton, ‘being reflexive is finding strategies to question our own attitudes, thought processes, values, assumptions, prejudice and habitual actions, to strive to understand our complex roles in relation to others’ (2009: 13).

It is also important not to be too hard on oneself if a realisation through reflection means that a personal bias must be acknowledged. Understanding the impact of socialisation, values, religious, cultural and other external influences will help us in this regard. In the social care context, becoming cognisant of how attitudes and feelings may impact on relationships with children, families and people who are supported gives us the capacity to recognise our own bias. Learning from our lived experiences identifies that personal values are fluid and can be developed and modified throughout the life course. In professional practice as a social care worker, a key skill is evaluating all intrinsic factors which have the potential to affect an outcome and then having the confidence that you have made the best possible decision.

Case Study 1

Kathy had commenced a 10-week work placement in a family resource centre in Galway and in her first week she was scheduled to work with a family recently arrived in Ireland. The family, originally from Syria, had moved from an emergency reception and orientation centre into their new home in Galway six weeks earlier. They are just one of many refugee families who arrived in Ireland from Syria via a refugee camp in Lebanon.

Although Ireland is no longer seen as a monoculture, most foreign nationals, like many new immigrants in other countries, have tended to live in more densely populated towns. Kathy is 19 and grew up in the far west of Connemara with Irish as her first language. She was very anxious at the prospect of working with an ethnic minority family as she had very little experience of cultures other than her own. This would be the first time that Kathy was to work with refugees; it was in fact the first time Kathy would have worked with people other than Irish. Kathy was also very aware of the lack of community engagement relating to a direct provision centre being built for asylum seekers locally and wondered how she would reconcile her own personal values, fears and biases. She was also unsure how the family would settle into the local community.

On the first day the Syrian family arrived into the resource centre, they came with their two daughters aged six and five years. Kathy was surprised at the level of English the children had, having assumed that this would be a barrier. Kathy had not sought clarification from her supervisor as to how the staff communicated with the family to organise the visit. Arrangements were initially made via an interpreter; however, on the day of the visit the parents arrived with the children only, and conversation with the parents was significantly limited as a result. Kathy thought the father did not to want to engage during the visit as he often looked away. Kathy enjoyed her time with the girls – when asked what they liked about Ireland, both replied ‘music’.

The next week when the family arrived, Kathy had brought something along with her to share with the girls, hoping to engage them more fully and build trust. Kathy was an accomplished fiddle player and when everyone was settled, she brought out the instrument and played ‘Galway Girl’ for the children. While she was very happy the children enjoyed her playing, Kathy was overwhelmed by their father’s response. Gesturing to be given the fiddle, Kathy reluctantly obliged, the father took it gently, tucked it under his chin, raised the bow and played ‘The Fields of Athenry’. And there, in a few bars of music, a connection was forged – in some ways, they did speak the same language.

Kathy learned a lot about herself and her assumptions and how her lack of life experience had influenced the decisions she was making. What Kathy had judged as rude or dismissive actions from the father during the first visit was explained by the interpreter who was present at the second visit as being his way to hide his embarrassment that he could not communicate in English like his children.

Kathy’s supervisor suggested that she ask questions in advance of the work she is included in during placement, so that she can research the culture and the context of this family’s arrival in Ireland. The manager praised Kathy for her initiative with the fiddle; however, she advised Kathy to investigate and reflect on where the family came from, how they were fleeing from their homeland because of civil war and might be traumatised.

When Kathy reflected on working with this Syrian family, she realised that, as a result of her lived experience there had been a shift in her perspective and a recognition that personal values are not fixed but are fluid and have the capacity to expand and evolve with exposure to new experiences. Being aware of one’s biases enables oneself to manage their impact in a given situation. Each life experience has the propensity to develop our self-awareness to a higher level, which in turn builds on our ability to view each new situation through a holistic, non-judgemental, strengths-based social justice and advocacy lens.

TASK 2

Reflect on a time when your belief system had the potential to impact negatively on your work or personal life. What learning came from this?

Impact of Personal Values and Life Experience on Professional Practice

Below are our personal experiences of how personal values and life experience have enhanced our professional practice.

From chapter author Caroline Coyle: In my experience of working in residential care, having knowledge of oneself is central to the work of a social care worker. Being grounded in oneself can be sensed by the young person in care. Having a strong internal locus of control, self-awareness and self-reflectiveness enables the young person to acknowledge you as a safe place to go to. For the young person, knowing that you will act as a buffer for their heightened emotions provides an opportunity for the young person’s needs to be identified, and a relational space to empower the young person to understand their exposed needs. A life facilitated in a non-traditional care setting is for many an extremely difficult and trying time in their emotional, social and intellectual journey. How their own values and belief systems are developed at this point can be bolstered with the opportunity to link with positive role models to expand and develop their world perspective. An important time indeed, which requires those charged with caring for children and young people to be mindful of their own attitudes to and level of awareness of those who share their world.

My personal philosophy when working in a social care context is to utilise creative methods such as poetry, writing, storytelling, drama, dance and art for various physical and psychological therapeutic benefits, e.g., to promote inclusion, forge pathways into the community, to provide a liminal space for the self to develop through interrelationships with others.

I have been using poetry, poetic inquiry and collaborative communal poem-making in my relational practice for many years, and these innate personal values have automatically transferred to my teaching philosophy. As a social studies lecturer focusing on the therapeutic use of drama in social care, I use the creative methods of arts-based media for collaborative participatory groupwork between the students and people we support in the community to facilitate individual critical reflection and learning on a deeper level.

From chapter author Imelda Rea: Core personal values – the things that are most important to us, the characteristics and behaviours that encourage us and guide our decisions – may not be fully our own true values after all. Discovering our values and identifying if these values run parallel to our work practice requirements may involve, as suggested below, analysis of self. We should not disregard or devalue current personal values automatically, however; we should take the time to understand what they are, how they developed within us over time and together with personal life experiences, so that we as practitioners can use the best of what we are to positively impact on others.

In my experience of working in residential care, it was essential to review personal values and learn how to manage them. Thinking about what exactly they were/are, to dissect the influences over one’s lifetime and consider how this can work in a positive or negative way in professional practice. Not understanding or recognising that our personal values and life experiences impacts our decisions could be the barrier to truly engaging with people we support. In the early 1980s in the UK, my introduction to working in residential care was a baptism of fire and is worlds apart from the current structure of child-centred care. The number of children in some residential homes were, at times, too high for the number of staff. Even without a formal social care education, I was prompted to review and manage the impact of my personal values. Upon reflection, many of the opinions I thought were my own were simply the absorbed opinions of others, with little analysis of those opinions or of how acting on them would impact on a supported child or young person.

It is worth noting that hard-won connections can be quickly lost from a lack of self-awareness; it is therefore essential to identify the roots of the ‘personal’ values we carry within us and consider, if they are one’s own, in this moment in time, fair and just. We may also have to re-evaluate the language we use as our personal values may not be reflected when we use outdated terminology.

Imelda’s professional practice is informed now by her lived experiences, her further developed personal values and her educational journey to date. Caroline’s professional practice is informed by her lived experience as a social care worker working with young people in residential care; her personal values of inclusion, advocacy and social justice; and her use of creative methods as a means of participatory engagement and self-reflective tools of inquiry.

Graduating as a social care worker is important to ourselves, our family and our employers. However, the right values, behaviours and attitudes to work effectively with people who need care and support is vital and should be consistently demonstrated in our day-to-day care of others to show the value we place on all we work with and for. We have both travelled extensively, living and working outside Ireland for many years, and in doing so have gained experience of diverse communities. It is often not until we move outside our ‘comfort zone’ that we really understand what it can feel like to be different or in a minority. Our beliefs and values may be in sharp contrast to those around us and may be challenged by others as a result.

It is important that social care workers have the ability to be open-minded, willing to examine all viewpoints and, if needed, to alter their perspective towards others. A productive and comfortable place to examine this area of self can be in a structured group session. The perspectives of other individuals, shared within a group setting, can offer a wealth of different viewpoints, and generate self-reflection.

Appropriately Managing the Impact of Personal Values and Life Experience

While understanding and taking ownership of the influences of our values and life experiences on one’s practice, the student must be cognisant of implementing strategies to manage the impact of these influences:

- Be open to the concept that your perspective can change.

- Actively train to increase self-awareness (‘Sharpen the Saw’).

- Make a conscious decision to be reflective. You may find that keeping a reflective diary or journal to ‘write out’ your feelings will help.

- Make yourself aware of how your personal values, attitudes and life experiences have the potential to influence your decisions and behaviours.

- Acknowledge that cultural, religious and gendered bias exists and may be inherited through a country’s collective consciousness and/or a colonial psyche.

- Reflect on your cultural background, heritage, familial, cultural and/or religious influences.

- Familiarise yourself with the evidential research and information relating to the various groups you may be working with in social care.

- Make note of the groups in history which have been specifically discriminated against and research these groups with regard to oppression and social injustice.

- Utilise Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model to understand the external influences of ecological systems on children’s development.

- Complete some of the self-reflective exercises on bias.

- Acknowledge a bias which becomes apparent. In the context of a situation which challenges you, breathe, recognise the bias, acknowledge it, and move on.

- Aim to complete a placement which you know will challenge you, your bias/es and your personal values.

- Engage in continuing professional development (CPD). Through CPD, theoretical and experiential learning, self-awareness is developed on an ongoing process across the life continuum.

- Knowledge of cultural awareness and implementing cultural competency in one’s professional practice is ethically and legally imperative in modern Ireland.

Conclusion

Throughout students’ academic journey, emphasis is placed on promoting the practice of self-awareness through reflection, enabling the student to understand and recognise the impact of personal values and life experience on professional practice.

Acquiring a critical understanding of the key threshold concepts of theoretical perspectives in social care empowers students to apply an effective relatability of theory to practice in the practicum; to deal with the everyday challenges which may arise; and to appropriately manage the impact of their personal values, biases and life experience in the authentic experiential learning space.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

In order to achieve this proficiency the student will need to understand and recognise the impact that their own personal values and life experience may have in any given scenario, case study or real-life situation.

The student will need to manage this impact on self and others, negotiating differences or challenges along everyday pathways in the social care context.

Invite the student to consider the sociological impact of how their own cultural, socioeconomic, religious and moral background (socialisation) has impacted on making them who they are today and who they aspire to be in the future.

Raise for discussion the concept of the fluidity of personal values and consider the changing nature of the impact of one’s own lived experience.

Learning opportunities can be provided for students in class-based placement preparation, utilising case studies for interpretation and recognition of personal values and biases.

Examples of case studies based on social care issues may include the following:

| LGBTQIA | Ethnic minorities |

| Travellers | Community development |

| Older people | Cyberbullying, social media |

| Social isolation | Residential and alternative care, foster care |

| Disability | Youth and youth work |

| Asylum seekers | Intergenerational solidarity |

| Physical, sexual or emotional abuse or neglect of children |

Invite students to reflect on how they would respond to the case study as a social care worker and, from their responses, to identify their personal values that impacted their decision. Once these personal values are recognised, the student then can begin to identify strategies to manage the impact of their personal values and life experiences.

Prior to entering student placement or new social care work environments, students should inform themselves of the organisational values and how these values are demonstrated in the culture of the organisation. Understanding and being aware of how our thoughts, attitudes and behaviours may impact those we are working within the social care context is vital. Being able to identify, recognise and manage the impact of one’s own life experience and values is indicative of a reflexive and effective practitioner.

Small-group discussions in a safe space (with guidance on appropriate self-disclosure and adherence to confidentiality) enable students to focus on self-reflection and becoming self-aware and reflexive. Group sessions provoking reflection must allow enough time for students to draw together their responses, share these with the group and be open to peer learning.

One must be cognisant that interactions of this nature, whether facilitated remotely or face-to-face, have the potential to draw unresolved issues to the fore. Student support services within the institution, e.g. counselling, should be identified, with encouragement to avail of these services if required, to promote student wellbeing. Understanding oneself and what motivates self is an enabler to care for others.

References

Bolton, G. (2009) ‘Write to learn: Reflective practice writing’, InnovAiT 2(12): 752-4, doi:10.1093/innovait/ inp105.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979) The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cousin, G. (2006) ‘Threshold Concepts, Troublesome Knowledge and Emotional Capital: An Exploration into Learning about Others’ in J.H.F. Meyer and R. Land (eds), Overcoming Barriers to Student Understanding: Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge. London and New York: Routledge.

Covey, S.R. (2004) The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. Bath, Avon: Simon and Schuster.

Corcoran, M.P. and Cullen, P. (eds) (2020) Producing Knowledge, Reproducing Gender: Power, Production and Practice in Contemporary Ireland. Dublin: UCD Press.

CSO (Central Statistics Office) (online) Census 2016 Profile 7 – Migration and Diversity. Available at <https://www.cso.ie/en/csolatestnews/pressreleases/2017pressreleases/pressstatementcensus2016r esultsprofile7-migrationanddiversity/> [accessed 3 January 2021].

Fenton, M. (201) Social Care and Child Welfare in Ireland. Empower Ireland Press. Goffman, E. (1956) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

Government of Ireland (n.d.) Healthy Ireland: A Framework for Improved Health and Wellbeing 2013-2025. Available at <https://assets.gov.ie/7555/62842eef4b13413494b13340fff9077d.pdf>.

Hanley, J. (1999) ‘Beyond the tip of the iceberg: Five stages toward cultural competence’,Reaching Today’s Youth 3(2): 9-12.

Jain, V. (2014) ‘3D model of attitude’, International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences 3(3): 1-12.

Jung, C.G. (1971) ‘Psychological Types’ in Collected Works. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lalor, K. and Share, P. (2009) ‘Understanding Social Care’ in P. Share and K. Lalor (eds), ApbCare (2nd edn). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Luft, J. and Ingham, H. (1955) ‘The Johari window: A graphic model of interpersonal awareness’. Proceedings of the Western Training Laboratory in Group Development, Los Angeles.

Lyons, D. (2007) ‘Just Bring Yourself’, master’s thesis. Technological University Dublin, doi:10.21427/ D7F622.

Mac Laughlin, J. (1999) Nation-Building, Social Closure and Anti-Traveller Racism in Ireland, Sociology 33(1): 129-51. Available at <http://www.jstor.org/stable/42856019> [accessed 16 January 2021].

Mason, J.L. (1993). Cultural Competence Self-assessment Questionnaire. Portland, OR: Portland State University, Multicultural Initiative Project.

McGinnity, F., Grotti, R., Kenny, O. and Russell, H. (2017). Who Experiences Discrimination in Ireland? Evidence from the QNHS Equality Modules, Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission. Available at <https://www.ihrec.ie/app/uploads/2017/11/Who-experiences-discrimination-in-Ireland-Report.pdf> [accessed 12 December 2020].

Omidi, Niloufar (2019) ‘Travellers’ culture is part of the country’s intangible cultural heritage, but is ignored, rejected and marginalised, Brainstorm, RTÉ, 23 October. Available at <https://www.rte. ie/brainstorm/2019/1023/1085102-is-part-of-irelands-cultural-heritage-in-danger-of-extinction/> [accessed 6 December 2019].

Pavee Point (n.d.) Recognising Traveller Ethnicity. Available at <https://www.paveepoint.ie/wp-content/ uploads/2015/04/EthnicityLeaflet.pdf> [accessed 10 January 2021].

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Wahler, E.A. (2012) ‘Identifying and challenging social work students’ biases’, Social Work Education 31(8): 1058-70, doi: 10.1080/02615479.2011.616585.