Chapter 64 – Laura Doyle (D5SOP2)

Domain 5 Standard of Proficiency 2

Understand and apply a human rights-based approach (HRBA) to one’s work including the promotion of the service user’s participation in their own care; ensure clear accountability; apply principles of non-discrimination; support other staff members to empower service users to realise their rights; be aware of the legality of actions within a service including the need to comply with any relevant legislative requirements including adhering to human rights obligations

|

KEY TERMS Human rights-based approach FREDA principles Participation Non-discrimination

|

Social care is … supporting people to realise and work towards their desirable future by establishing strong interpersonal relationships and using a human rights- based approach. |

Introduction

In Chapter 3 I introduced the concept of the human rights-based approach (HRBA) in social care in the context of examining of how social care workers act in the best interests of service users with due regard to their will and preference. This chapter examines how practitioners can apply a rights-based approach in their own practice, while upholding the principles of non-discrimination across all aspects of their work. We will also look at how social care workers can increase and promote participation of service users and also examine the topic of accountability. Opportunity will be provided throughout for the reader to reflect on how they can support this proficiency in practice.

Human Rights

Human rights, as stated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), are the universally agreed basic rights and freedoms that should be available to all people simply based on their humanity. We are all born with human rights regardless of nationality, gender, religion or any other status. According to Harris and White (2018), human rights are absolute, qualified or limited.

- Absolute rights cannot be restricted in any circumstance; they include rights such as the right to life or the right to be free from torture.

- Qualified rights can be infringed upon provided there is justification, e.g., the right to freedom of expression, the right to privacy.

- Limited rights can be restricted, or limited, by specific circumstances such as the right to liberty, which can be restricted when a crime has been committed and a person is imprisoned. (Harris & White 2018; Council of Europe 1950).

There are various international and national human rights instruments. The table lists some of the main human rights instruments that relate to social care:

|

International Human Rights Instruments |

Irish Specific Legal Framework |

|

Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948 (not a legally binding instrument but a declaration of agreed-upon values and standards) European Convention on Human Rights 1950 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1965 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women 1979 Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment 1984 Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families 1990 International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance 1990 UN Principles for Older Persons 1991 (nota legally binding instrument, but agreed-upon principles which should be incorporated by local governments in frameworks and programmes) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006 Charter of the Fundamental Rights of the European Union 2012 |

Bunreacht na hÉireann (Irish Constitution) 1937 Employment Equality Acts 1998-2015 Equal Status Acts 2000-2015 Mental Health Act 2001 European Convention on Human Rights Act 2003 Disability Act 2005 Health and Social Care Professionals Act 2005 Citizens Information Act 2007 Health Act 2007; and Health Act 2007 (Care and Support of Residents in Designated Centres for Persons (Children and Adults) with Disabilities) Regulations 2013. Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission Act 2014 Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015 |

Human Rights-Based Approach

Garcia Iriarte (2016) describes a human rights-based approach, in the context of examining different disability models, as the way that society provides for equal opportunities for all members to realise their rights regardless of difference. Difference in this context is seen as an inherent part of the human condition. Dukelow and Considine (2017) view a rights-based approach as an approach ‘which advocates a guaranteed level of social provision as a matter of right and entitlement’ (Dukelow & Considine 2017: 323).

Curtice and Exworthy (2010) define a human rights-based approach to care as a ‘bottom-up’ approach whereby the clinical processes, organisational practices and culture of a service support and protect the human rights of people who use social care services. HIQA (2019a) describes a human rights-based approach as an approach that promotes, supports and protects the inherent rights of people using social care services and supports, and guarantees support as a matter of right.

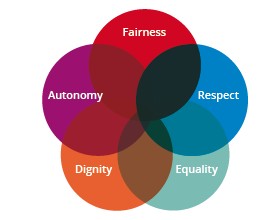

The FREDA Principles

According to Curtice and Exworthy (2010) a human rights-based approach can be supported by adhering to the core principles of fairness, respect, equality, dignity and autonomy, or the easy to remember acronym FREDA. HIQA introduced the FREDA principles to Irish health and social care services in 2019 in its document Guidance on a Human Rights-Based Approach to Care and Support in Health and Social Care Services. The FREDA principles were first introduced by Curtice and Exworthy (2010) and have already been used in the English health and social care services (HIQA 2019b). A breakdown of each principle is outlined below.

|

Fairness |

The principle of fairness means that due consideration is given to the person’s will and preference in relation to a decision to be made about their care or support. The person is at the centre of the decision-making process; their opinions and views are sought and weighed against any other important factors in relation to the decision being made. |

|

Respect |

Respect applies not only to the person but also to their value system. This principle upholds the objective, unbiased consideration and regard for the rights, values, beliefs and property of other people. |

|

Equality |

The principle of equality warrants that people are not treated differently or less favourably than other people based on any of the grounds of discrimination as set out in law. Equality also ensures that people are afforded equality of opportunity. |

|

Dignity |

The principle of dignity ensures that each person is treated as a human being, that they are treated with compassion, care, and in a way that supports their self-respect. |

|

Autonomy |

Autonomy is the principle of self-determination whereby a person makes decisions on how they live according to their own values, beliefs and preferences. It involves a person using a service being informed about all aspects of their care and support. |

The PANEL Principles

PANEL is another human rights-based approach, adopted by the Scottish Human Rights Commission in their National Action Plan for Human Rights. PANEL focuses on understanding the core underlying values and core principles of human rights instruments which, in this approach, are participation, accountability, non-discrimination, empowerment and legality (Scottish Human Rights Commission, cited in Smith 2018):

|

Participation |

The principle of participation means that the person should participate in all aspects of decision-making that affect them. |

|

Accountability |

Accountability requires that human rights standards in services are monitored to ensure clear accountability. |

|

Non-discrimination |

All forms of discrimination on any of the protected grounds enshrined in law are prohibited. |

|

Empowerment |

Empowerment, as a human rights principle means that people are supported to realise and exercise their human rights. |

|

Legality |

The principle of legality ensures that practices and supports are grounded in human rights instruments and laws. |

Source: Scottish Government 2015

On further examination of the proficiency it becomes clear that this proficiency itself has been designed and based on the PANEL principles:

- The promotion of the service users’ participation in their own care

- Ensure clear accountability

- Apply principles of non-discrimination

- Support other staff members to empower service users to realise their rights

- Be aware of the legality of actions within a service.

Supporting a Human Rights-Based Approach using the FREDA or PANEL Principles

A human rights-based approach in social care is the integration of principles and standards of international human rights instruments into social care policy and practice. A human rights-based approach empowers people to know and claim their rights (Smith 2018). When we discuss human rights in social care, many rights come into focus, including:

- The rights of the child

- The rights of people with disabilities

- The rights of older people

- The rights of women

- The rights of people with mental health conditions

- The rights of members of socially marginalised groups

- The rights of the social care worker.

Understanding and having extensive knowledge of all the different human rights instruments can be a daunting task; however, Curtice and Exworthy (2010) argue that understanding and implementing the FREDA principles negates the need for technical knowledge of various rights instruments as the FREDA principles capture the underlying concepts and principles which underpin human rights instruments. As social care workers, we have a duty to uphold the rights of people we support so we should be aware of and have knowledge of the different human rights instruments that apply to our role. The FREDA or PANEL principles will help the practitioner promote and adopt a human rights-based approach in their work without the need to spend an excessive amount of time on the legalistic interpretation and implementation of rights, instead focusing on the underlying values and principles. Implementing a human rights-based approach in social care can be achieved by following these principles and embedding them as part of our everyday practice and in our interactions with service users.

Case Study 1

A Human Rights-Based Approach in Practice

Margaret is a woman in her forties who lives at home with her elderly mother. Margaret has an intellectual disability and attends a day service centre where she receives support from her social care worker, Jane. On arriving at the centre on Monday, Margaret informs Jane that she won’t be attending the centre on Wednesday as she has a doctor’s appointment. Jane asks Margaret if she would like to let her know why she is attending the doctor. Margaret says that her mam wants her to have a smear test. Margaret informs Jane that she doesn’t know what a smear test is or what it is for. Jane sits down with Margaret to explain what a smear test is and what it is used for. Margaret is initially shocked by this information and states that she does not want to have it done but is worried that if she doesn’t she will upset her mam. Jane explains to Margaret that she does not have to have the smear test if she does not want to.

Worried that Margaret’s views are not being sought or supported, Jane seeks further guidance from her line manager. Her line manager asks Jane to seek consent from Margaret to contact Margaret’s mam for more information and to arrange a meeting to put a plan together on how Margaret will be supported using a human rights-based approach. After getting consent from Margaret, Jane contacts her mother, who informs Jane that there is a history of cervical cancer in Margaret’s family and that she booked her an appointment because she believes that early detection is key, as Margaret is at risk.

A summary of the key steps taken that followed a human rights-based approach:

- Margaret was informed at all stages of the decision-making process and her will and preference and her consent was continuously sought.

- With Margaret’s consent Jane arranged to have a meeting with Margaret, herself and Margaret’s mother to discuss Margaret’s will and preference.

- Margaret was supported to communicate to her mother her decision not to attend the doctor’s appointment for the smear test.

- Margaret’s mam felt that because Margaret has an intellectual disability she is not able to make decisions for herself and should just go ahead with the smear test.

- Jane spent time explaining to Margaret’s mam that although Margaret has an intellectual disability, she has the same right to make decisions on her own healthcare as anyone else.

- During the meeting, Margaret stated that she doesn’t know much about cervical cancer and the smear test but would like to find out more and that maybe the test is something she could do in the future.

- Jane asked Margaret if she would like to put a plan in place to find out more about cervical cancer and the smear test in a way that she can understand. She agreed to this.

- Jane developed a plan for Margaret to be informed about cervical cancer and the smear test using accessible language that Margaret will understand, and given over a period of time that is conducive to Margaret’s decision-making.

- Jane regularly sought guidance and support from her line manager to ensure accountability and also to ensure that she was upholding a human rights-based approach in line with her own obligations and duties as a social care worker. Jane documented all stages of her work that supported Margaret’s human rights in line with her organisation’s report-writing policy and procedures.

- Jane and Margaret regularly work together on her plan to find out more information on cervical cancer and the smear test so that Margaret can make an informed decision on her healthcare.

Promoting Participation

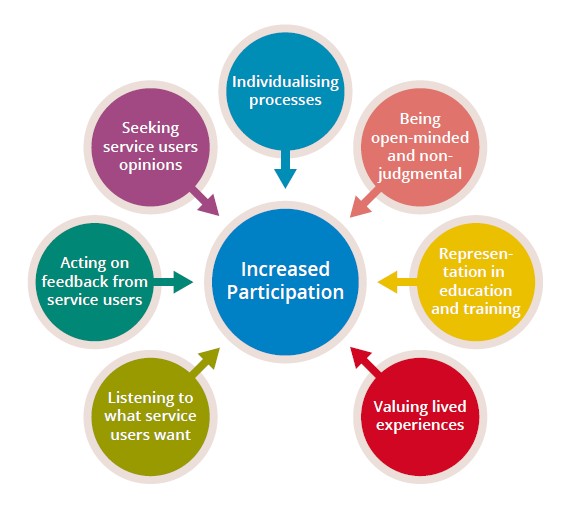

One of the key ways in which social care workers can embed a human rights-based approach in their practice is by ensuring that service users are involved and participate in all aspects of their care. Participation involves service users playing a fundamental role in influencing and shaping the services they use. According to Warren (2007), participation in social care can take place in many different forms, including:

- Individual care planning and reviews

- Service planning and development

- Staff recruitment and training

- Research.

In disability services in Ireland there is a fundamental philosophy that there is ‘nothing about me without me’, meaning that people need to be involved in all decisions and aspects of their care and support; their opinions and views need to be actively sought at all stages of any decision-making processes. For example, at an everyday practice level it could mean the involvement of the service user in choosing who they receive support from, or at a governance level by the service user being involved in the development of organisational policies and procedures. Decisions on services and supports for people should never occur without the involvement of the person, or persons, to whom decisions relate. Decisions on the care and support of a service user should only occur with participation and involvement of the service user at the centre of this process. This can occur and be supported by the social care worker individualising the decision-making process, for example designing any decision-making interventions around the person’s attention span and the amount of time they can focus on a particular issue, so that it is conducive to the person’s decision-making capacity. Some of the ways in which practitioners can support this is by having service users choose where meetings take place, for how long, and who will attend.

TASK 1

Place yourself in the position of a service user who is being supported by a social care worker. How would you like to be supported to participate in yourown care?

Social care workers will need to utilise their problem-solving and negotiating skills where there are instances of resistance or conflict with the service user; it is in these moments that the relationship between the practitioner and service user is of utmost importance. As social care workers we need to continuously look for and identify opportunities to promote participation for service users in all aspects of their care. The illustration below, based on elements identified by Beresford (cited in Harris & White 2018), highlights some more ways in which social care workers can increase service user participation.

Accountability in Social Care

Social care workers have several lines of accountability: to act within the law; to act according to codes of conduct as set out by regulatory bodies; organisational accountability to line managers and organisational policies and procedures; and accountability to service users. Social care workers are expected to adhere to these various lines of accountability.

Simply put, accountability means being answerable to questions relating to personal standards of professional practice. For social care workers, professional accountability ensures that we operate and adhere to practices and standards as set out by law in relation to our practice. To help ensure accountability, it is important that social care workers are aware of the various lines of accountability in relation to their practice and also various legal frameworks that underpin our practice, some of which are outlined in Figure 1 above. The code of conduct for social care workers is legally outlined in the Social Care Workers Registration Board Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics Bye-Law 2019, which sets out the standards of ethics, conduct and performance expected of registered social care workers. To ensure accountability it is important that social care workers adhere to this code of professional conduct and ethics.

Principles of Non-discrimination

Discrimination means that one person is treated less favourably than another person in a comparable situation. The Equal Status Acts 2000-2018 prohibit discrimination in relation to access to and use of goods, services, accommodation and education, and set out nine grounds of discrimination: gender, civil status, family status, sexual orientation, disability, age, race, religion and membership of the Traveller community.

There are two types of discrimination; direct and indirect. Direct discrimination is when a person is treated less favourably than another based on any of the protected grounds. Indirect discrimination occurs when practices, laws or procedures place a person who differs under any of the protected grounds at an unfair disadvantage as compared to another person (IHREC 2020). According to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2009) the principle of non- discrimination seeks to ensure that rights are exercised without discrimination. Within social care the principle of non-discrimination could be interpreted as the provision of care and supports to service user without discrimination based on any of the protected grounds. As social care workers it is important that we uphold and follow principles of non-discrimination in all aspects of our work. Upholding principles of non-discrimination in practice involves supporting other colleagues and staff to promote the rights of service users.

Conclusion

This proficiency can at first appear a challenging proficiency to grasp. However, as shown in this chapter, by breaking down the proficiency we can begin to see how the different aspects of a human rights-based approach, non-discrimination, participation and accountability all interlink and are at times interdependent on one another. As social care workers it is imperative that we follow these principles throughout the course of our work and that we are constantly making ourselves aware of various legal and regulatory frameworks relating to our work. Embedding the FREDA or PANEL principles into our everyday practice can offset the need for a thorough legalistic knowledge of all these different frameworks. This does not negate the need for social care workers to have knowledge of these legal and regulatory frameworks but rather supports their practical implementation in social care practice.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

As discussed, this proficiency can at first seem a complex proficiency for students to grasp simply because it can appear to have many different aspects to it. Breaking down the proficiency, as outlined in this chapter, can help the social care student get a grasp of the proficiency’s fundamental principles and begin to see how they correlate, relate and interlink with one another. The student can then start to reflect on how they might support this proficiency in practice and what potential obstacles or barriers might be faced by social care workers in practice. It is important that students are supported to reflect on societal views of various marginalised groups and how barriers exist that place these groups at a disadvantage. This proficiency could be linked directly to subjects in the social sciences, including law, public policy and sociology. There is ample opportunity for the student to begin to interlink many theories in these subjects to support their theory-to-practice skill set.

To support the learning for this proficiency, it is fundamental that students to reflect on how they could implement a human rights-based approach in their practice and what different skills could support this. The Guidance on a Human Rights-based Approach in Health and Social Care Services (HIQA 2019) provides many case studies on a human rights-based approach which can be used by practice educators in their teaching with students to help facilitate discussion and refection on how this approach is supported in practice and on instances where this approach is not supported in practice. The practice educator could utilise reports or documentaries of real-life instances as discussion and reflective pieces.

References

Council of Europe (1950) European Convention on Human Rights. Council of Europe.

Curtice M, and Exworthy, T. (2010) ‘FREDA: A human rights-based approach to healthcare’, The Psychiatrist 34(4): 150-6.

Dukelow, F. and Considine, M. (2017) Irish Social Policy: A Critical Introduction (2nd edn). Bristol: Policy Press.

Garcia Iriarte, E. (2016) ‘Models of Disability’ in E. Garcia Iriarte, R. McConkey and R. Gilligan (eds), Disability and Human Rights: Global Perspectives. London: Palgrave.

Harris, J. and White, V. (2018) Dictionary of Social Work (2nd edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2019a) Guidance on a Human Rights-Based Approach to Care and Support in Health and Social Care Settings, Dublin: HIQA.

HIQA (2019b) Background document to inform the development of guidance on a human rights-based approach to care and support in health and social care settings, Dublin: HIQA.

IHREC (Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission) (2020) The Equal Status Acts 2000-2018: A guide to your rights if you are discriminated against in accessing goods or services. Available at: <https://www.ihrec. ie/app/uploads/2020/10/IHREC-Equal-Status-Rights-Leaflet-WEB.pdf> [accessed 9 November 2020].

Smith, S. (2018) Human Rights and Social Care: Putting Rights into Practice. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press.

Scottish Government (2015) National Health and Wellbeing Outcomes. Available at: <https://www.gov. scot/publications/national-health-wellbeing-outcomes-framework/pages/9/> [accessed 29 November 2020].

UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2009) General comment No. 20: Non- discrimination in economic, social and cultural rights (art. 2, para. 2, of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights). Available at: <https://www.refworld.org/docid/4a60961f2.html> [accessed 14 November 2020].

Warren, J. (2007) Service User and Carer Participation in Social Work. Exeter: Learning Matters.