Chapter 69 – Denise Lyons and Sharon Claffey (D5SOP8)

Domain 5 Standard of Proficiency 8

Understand the role and purpose of building and maintaining relationships as a tool in the delivery of social care across the lifespan in a variety of contexts.

|

KEY TERMS Variety of contexts Relationship-based social care work Building and maintaining relationships |

Social care is … relationship-based practice that involves having a non-judgemental attitude, being consistent in using a strengths-based approach and, in turn, empowering people to reach their full potential. |

Five proficiencies of the eighty are about relationship, referring primarily to the relationship between the worker and the service user (Chapters 35, 36, 69 and 70); the professional relationship with colleagues (Chapter 38) is also acknowledged and valued.

|

Domain |

Chapter in this book |

Focus on the Relationship |

|

D2 SOP12 (2017: 6) |

Ch 35 by Natasha Davis |

‘Be aware of the concepts of power and authority in relationships with service users’ |

|

D2 SOP13 (2017: 6) |

Ch 36 by Des Mooney |

‘Understand the need to build and sustain professional relationships’ (with everyone) |

|

D2 SOP15 (2017: 6) |

Ch 38 by Des Mooney |

‘Understand the role of relationships with professional colleagues … based on mutual respect and trust’ |

|

D5 SOP9 (2017: 9) |

Ch 70 by Teresa Brown |

‘Critical understanding of the dynamics of relationships’ (with service users), focusing on ‘concepts of transference and counter-transference’ |

This chapter focuses on explaining the role and purpose of relationships through a discussion on relationship-based social care work, concluding with practical recommendations on how to build and maintain relationships across the lifespan and within different contexts.

Variety of Contexts

Social care workers build and maintain relationships with children and/or adults, through the delivery of care across a variety of social care services. Depending on the nature of the service and the needs of the service users, this relationship may be short and focused, or long and spanning several years, or a full life-time, terminated only by the death of the service user or the retirement of the worker.

The context, the social care setting, will determine the length of time and the quality of access the worker has with the service user. McCormack et al. (2002: 94) state that ‘context specifically means the setting in which practice takes place’. Context is also defined as the background for all social interactions which are influenced by cultural, historical, political and economic constructs (Burr 2015). However, context is more than a backdrop; context is a social, active and emergent space (Wenger 2010), shaped by the relationships within. Therefore, context is practice (Barnett 1999), people, structures and relationships. Social care services are always in a state of flux, changing to meet the diverse needs of service users, adapting to new people, and adjusting to the current economic and political climate. The context is the physical representation of how the practice is influenced by policy and valued by society. These socially constructed and ever-changing contexts are places that are meaningful (Tuan 2012) and spaces that are lived-in and loved (Merleau-Ponty 2012).

Social care workers inhabit the contexts of practice; they engage in the activities and movements of social care, through their holistic and embodied practice, from physically pushing a wheelchair or using a hoist, sitting beside someone in the shared space, to cognitively and emotionally ‘being present’ (Digney & Smart 2014). The contexts of practice are diverse, and each worker is engaged in completely different activities depending on the needs of the service user in that place, space and time. The discussion on varied contexts of care requires some understanding of the concepts of place and space (Lefebvre 1991). McDowell (1996: 29) articulated a relational definition of space, where ‘all social relationships occur somewhere and result in connections between people and places’. Place is presented as the ‘nodes’ of space, a ‘symbol’ of space that is ascribed with ‘personality and spirit … the sense of place’ (Tuan 2012: 388-9). The personality of a place is felt, remembered with affection or hate, and recollected from a smell (Tuan 2012), taste or photograph. Workers and service users shape the varied contexts of social care practice and are ultimately shaped by them.

The theory of material culture, which studies the relationship between people and objects, is also relevant to understanding the impact of social care contexts (Hicks & Beaudry 2010) on people, relationships and practice. The material culture of contemporary social care (Woodward 2007) includes the objects and practices of everyday life in the different settings. This includes, but is not limited to the furniture, decorations, utensils, fabrics, and also the objects used to provide care; the wheelchairs, hoists, slings, medicine cabinets, the locked press, the keys, the office and the records, to name a few (Hicks & Beaudry 2010). Material culture also includes the remnant artefacts from the past which continue to influence the use and feel of the space, from the architecture of the building, including the location of the setting, to the size of the rooms, the previous use of the space, and the dated photographs that adorn the walls (Davies et al. 2013). Within these buildings converted into social care settings, social care workers, through relationship-based practice, give life to ordinary places for meaningful practice.

TASK 1

Think of a social care setting, focusing on the building itself. Did it feel homely, clinical, warm or cold? How did the ‘context’ and its ‘material culture’ make you feel?

Relationship-based Social Care Work

As the view of the relationship in SCWRB’s ‘standards of proficiency’ is presented as a threshold, social care needs a theoretical frame underpinning the knowledge base that presents the relationship as core and central to practice (Lyons 2017). Scholarly discourses on the relationship in social work, social pedagogy and child and youth care (Garfat 2004, 2008; Stephens 2013; Egan 2014) have influenced social care workers and educators in Ireland (McHugh & Meenan 2013; Lyons 2009, 2013; Digney & Smart 2014). The various relationship approaches may differ slightly in position and context, but all involve one person engaging with another while they are doing things together and being with each other. Trevithick (2003: 163) presented a history of how the relationship, once seen as essential for best practice, had fallen ‘out of favour’, which led to the revisionist ‘relationship-based social work’ framework. The characteristics of this framework (Wilson et al. 2011) are relevant to the relationships in social care work and form part of the four core characteristics discussed in this chapter. The relationship-based social care work framework presented here is influenced by Wilson et al. (2011), the Standards of Proficiency for Social Care Workers (SCWRB 2017) and the perspectives of social care workers in Ireland (Brown 2016; Lyons 2007, 2017).

In relationship-based social care work, workers begin to understand a person through the sharing of a life story. Stories about the past, and present experiences, help us ‘to understand oneself and others’ (Chamberlayne et al. 2000: 7). Through listening empathically to others, we can learn how they became who they are and ‘understand our own histories and how we have become who we are’ (Chamberlayne et al. 2000: 7). The following case study was extracted from two chapters in Howard and Lyons (2014) Social Care: Learning from Practice. The two chapters (Fenton 2014; King 2014) are based on the relationship between the social care worker (Maurice Fenton) and a young person in residential care (Keith King). Segments from the two chapters are presented here as examples of the four characteristics of relationship-based social care work. Although relationships take time to develop (Lyons 2017), Keith and Maurice’s relationship in the children’s residential centre lasted approximately five months.

Holistic Psychosocial View

All people are unique and therefore our relationships with them are different from all other relationships we have developed and experienced. The people we work with are complex and multifaceted and relationship-based social care work accepts that people are influenced both by the internal world of feelings, emotions and behaviours, and also by the external world, including their past experiences and how they are treated by society, policy and the people around them (Wilson et al. 2011). This is a psychosocial approach (Newman & Newman 2012) to social care work that acknowledges the interaction between biological, psychological and societal systems and their influence on the service user. ‘Holistic’ refers to the relationship of the whole person (body and mind) of the worker with the whole person (body and mind) of the service user. We need to know people well in order for them to be comfortable with us, physically, emotionally and cognitively. Social care practice is the embodiment of both the worker and the service user in the shared space of practice; we work and live together. ‘Head, heart and hands signifies this holistic approach’ (Ghate & McDermid 2016: 6) and ‘all three being essential for the work’ (Petrie et al. 2006: 4). We can apply a holistic, psychosocial approach within our relationships with others by learning about them through their story.

Case Study 1

Keith was born into a large family ‘that suffered physically, socially and psychologically through domestic violence and alcoholism’ (King 2014: 37). Keith’s parents were loving when alcohol was not involved, and he learned to read their mood and level of intoxication by their body language and dress. Keith had a reputation in school and local community as a thief (explained in his chapter) and spent large amounts of time without adult supervision or care.

Fenton (2014: 48-49) described Keith’s focusing on the positives in his relationship with Maurice and with his mother, as Keith’s way of “distinguishing the love from the harm”. Maurice understood Keith’s need to ‘act in socially unacceptable ways’ as a response to childhood trauma and a need to survive. Keith presented with a ‘range of complex and challenging behaviours’, which Maurice understood as communicating trauma and he responded with kindness, care, patience and trust, which had an emotional and long-lasting impact on Keith.

Adheres to the FREDA Principles

The FREDA principles (Curtice & Exworthy 2010), which were adopted by the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA 2019), are fairness, respect, equality, dignity and autonomy. They represent the values within the relationship-based social care relationship.

Case Study 2

Keith noted how Maurice ‘made a massive impression’ on his life (King 2014: 40) and that he knew he could trust him because he experienced equality when Maurice ‘always stood up and advocated for me’. Keith experienced respect when Maurice showed genuine interest in him and his needs. Keith experienced fairness, dignity and autonomy when he felt heard, listened to and nurtured by Maurice. Also, when the manager of the unit genuinely apologised to him for making a mistake in the way she had spoken to him.

TASK 2

Please read HIQA’s Guidance on a Human Rights-based Approach in Health and Social Care Services (2019) and list examples of times Keith was shown equality, respect, fairness, dignity and autonomy.

Use of Self and Body

Relationship-based social care work acknowledges role of self in practice including the body and the mind. Relationship-based practice in social care is holistic and embodied, a mutual collaboration between the worker and service user, centring on being supportive, and working within the relationship (Cameron & Moss 2011). Johnson (1987) described embodiment as involving the whole body in meaning-making within practice. Social care work is embodied through the lived experience, decision-making, and all the movements and practices of the people we work with and the services we work in. Social care workers have ‘a body’ (Johnson 1987) ‘through which [they] act in the world’ of practice (Merleau-Ponty 2012: 140). Workers also have a mind, which is engaged in being present and thinking about how to care for the person; and hands, used in physically supporting them to meet their needs. Embodiment for social care workers is not just about the engagement of the body, the thoughts and feelings connected to practice, but the overall experience of being in the world.

Case Study 3

When Keith entered residential care, he was introduced to the man (Maurice) who would become his key worker. Keith recognised him immediately as the man he had observed playing naturally with another child and noted he was kind and caring; he felt he could trust him. Maurice was using his authentic self (Brown 2016) in his play and care, which is a part of his relationship with the children in his care. Maurice described this as a ‘willingness to show vulnerability and appropriately admit mistakes’ and to show ‘unconditional positive regard’ (Fenton 2014: 50-2). Maurice made sure that Keith knew that he liked him and enjoyed spending time with him and was invested in their relationship. Keith experienced this as trust.

When we have a relationship with another person, we share a part of ourselves, and we also put at risk our emotional self (Clarke 2003; Lyons 2013). Potentially, there is pain in relationships, especially when the worker has become emotionally involved in trying to create an experience that is genuine, warm and real (McMahon 2010). Workers are challenged in their training and practice to adopt the values and beliefs of unconditional positive regard and empathy (Lalor & Share 2013) for the service users (Payne et al. 2009). But helping and supporting people can be emotionally difficult and challenging for the worker and workers need to recharge with self-care and learning how to switch off and resist bringing work (feelings, thoughts and concerns) home.

Relationship is the Centre of Practice

Relationship-based social care work is the centre of all interventions in planned practice, and the service user is the centre of everything. In Chapter 67, the SKIP Model (Lyons & Reilly, forthcoming), describes the relationship as the heart of evidence-informed practice in social care work. Social care workers learn ‘what social care work is’ within their specific setting, how to ‘do’ social care work in order to meet the needs of the people using the service through the relationship. The relationship is the core of social care practice in all settings (Kennefick 2006; Lyons 2009). Workers provide care and nurturing, demonstrate meaning and create meaningful moments (Digney & Smart 2014) and establish trust by being genuine and consistent (Howard & Lyons 2014). Social care work involves getting to know a person and sharing your time, experience, knowledge, humour, values, feelings and emotions with them. During the time you spend with the service user, information is being communicated, non-verbal and/or verbal, from you and between you. By viewing the relationship as the centre of practice, organisations will value and support the time needed to develop a relationship.

TASK 3

Read the two chapters and find more examples of the four characteristics of relationship-based social care work within the text.

Fenton, M. (2014) ‘The Impossible Task: Which Wolf will Win?’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons, Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 48-59). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

King, K. (2014) ‘There’s no Place Like Home: Care and Aftercare’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons, Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 37-47). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Building and Maintaining Relationships

This section of the chapter outlines the steps required for building and maintaining relationships.

The first step encourages the worker to take a step back, look inwards and examine their own values and attitudes, step two, establishing rapport, is the ‘getting-to-know-you’ phase, which moves to step three – the ‘relationship dance’ between the worker and the service user.

Step 1 – Look Inwards

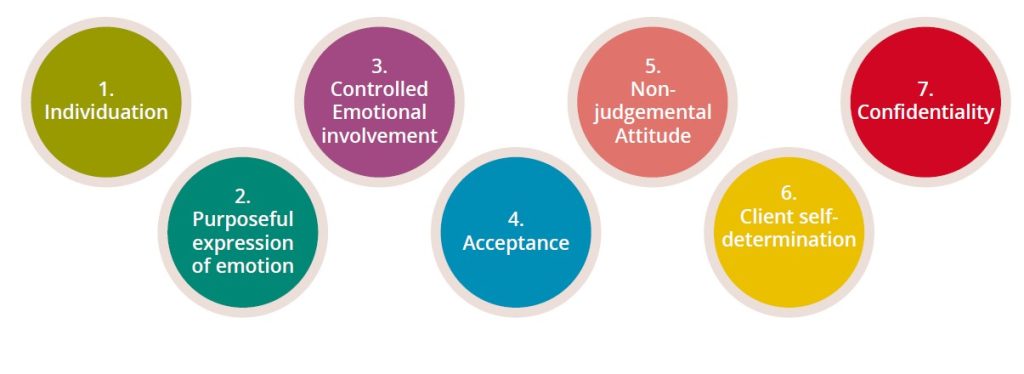

The skills in building a relationship with others begins with the worker, and the attitudes, values and beliefs they hold about people. The Casework Relationship by Felix Biestek (1957) has seven principles which outline the appropriate values, attitudes and knowledge needed before you start to build a relationship with a service user. Although this theory was published in 1957, and was part of my own social care education in the 1990s, it is still relevant today.

The Casework Relationship by Felix Biestek (1957)

’As with all practice approaches, a great deal depends on the knowledge, skills, values and qualities that’ social care ‘workers bring to the work’ (Trevithick 2003:164). The seven principles are difficult to achieve and require a commitment to consistently reflect and check in on your attitudes and beliefs and update your knowledge on how to become more empathic and less judgemental in practice.

TASK 4

Watch the video on the Seven Principles of the Casework Relationship:

Write down the key steps involved in each principle.

Step 2 – Establish Rapport

The aim of the first stage of building a relationship is to help the service user to feel relaxed and safe in your company. You are not trying to ‘do’ in this stage but aiming to ‘be’ your genuine self (Kroll 2014).

Start by learning the names of all the service users you will encounter daily, then give yourself the task of remembering one important fact about each person. You may be tested by the service user at this stage of relationship building, so take a mental note of all their likes and dislikes, what team they support, what music they like, if they take sugar in tea or where they like to sit. By mirroring and matching the service user, by folding your arms if they have folded their arms (mirroring) or folding your legs if they have folded their arms (matching). As you tune into the person’s rhythm (Garfat & Fulcher 2012), their breathing and speaking, and use of space, you will help them to feel heard, seen and valued. Remember, every person is unique, so relax, watch, listen and learn.

Step 3 – The Relationship Dance

As you begin to establish familiarity with each other the relationship moves from the ‘establishing rapport’ stage to the ‘relationship dance’. Kroll (2014: 73) called this stage the ‘coming together stage’ where communication is received and responded to, people are tuning in to each other, and a safe holding space is created, where ‘taking risks can be thought about’. The following vignette from Garfat (2004) explains the ‘dance of the unknowns’, where the relationship is new and they dance betwixt and between this liminal and unknown space within the developing relationship.

‘We don’t know her, so we tread gently; we are unsure how to be so we move to our neutral therapeutic place and reach out tentatively, exploring, like her, the unknown territory. And because we move gently, we avoid any provocation which might cause a reaction. So, if this is correct, here we are, us and the young person, exploring the territory together, reaching out to see how the other will respond, finding out what is safe, how we can be here, what works. It is the ‘dance of the unknowns’, and it continues until one of us pushes a little more, moves to test the reality of her perceptions, reaches beyond the superficial safe place we establish inthe early stages of relationship development. And in this, it is all so normal. We explore who this new person is; we explore how they are with us; we explore whether or not we are interested in taking this relationship to a different depth. We test. We move closer and move back. We explore’ (Garfat 2004).

In this dance, ‘the experiences, feelings and expectations that both participants bring into the relationship, the way in which connecting biographies play their part, and the defence mechanisms that come into play’ (Kroll 2014: 73) become the steps we navigate together. This unknown space in the dance is defined as the ‘safe uncertainty’ stage of relationship development in relational child and youth care (Featherstone et al. 2014). ‘Preparation, making a warm, human connection, empathy, sympathy and intuition’ (Kroll 2014: 78) are the ingredients needed to create safety and establish trust. Emotional intelligence is essential to read the dance and to respond appropriately, and to know when to apologise when you get the steps wrong. Sometimes relationships are difficult and experienced as ‘stumbling through’ (Hingley-Jones & Ruch 2016), especially if the person does not trust or know the staff member, or is dealing with their own issues. Ormond (2014) argues that even though the work can be very difficult and sometimes threatening, it is very important to relate to others in a non- blaming way, and ’survive’ the work without becoming vindictive. He advises workers to be slow to judge, quick to use humour, and to become less self-conscious (Ormond 2014).

To conclude, relationship-based social care work is a useful framework to help workers remember that the relationship is the centre of our practice. This approach acknowledges the role of self, the uniqueness and complexity of the people we are building relationships with and how they are influenced by the systems that surround them, and finally, how the FREDA principles (Curtice & Exworthy 2010) will help us remember to treat people with respect and dignity. We can learn how to build and maintain relationships by becoming more aware of our own values and beliefs, learning techniques to establish rapport and developing our emotional intelligence so that we can understand the subtle communication cues and steps to help us to ‘dance’ and ultimately make a difference in one person’s life.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

As building and maintaining relationships is the ‘nuts and bolts’ of your social care practice:

- Share your knowledge on how to establish rapport with the service users in your unit. Do you mirror or match in your body language and gestures?

- Ask the student to learn the names of all service users and at least one piece of information that is relevant and important to them.

- In the relationship dance, talk about relationships that you found challenging and discuss with the service user the ways you worked this through.

- Do a relationship chart of the service that outlines:

-

- The length of time people have used the service and worked there.

- The people who used to live or work there.

-

- Ask questions about the building, what changes have happened over the years and how have these changes impacted on the services and the ‘feel’ of the building.

- Review the seven principles of the casework relationship. Discuss how you apply individuation, purposeful expression of emotion, controlled emotional involvement, acceptance, non-judgmental attitude, recognise client self-determination and adhere to confidentiality in your relationships with the service users.

References

Barnett, C. (1999) ‘Deconstructing context: Exposing Derrida’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 24(3): 277-93.

Biestek, F. P. (1957) The Casework Relationship. London: Allen and Unwin.

Brown, T. (2016) ‘Hear Our Voice: Social Care Workers’ Views of Effective Relationship-based Practice’, PhD thesis, Queens University, Belfast. Available at <http://isni.org/isni/0000000464238827>.

Burr, V. (2015) Social Constructionism (3rd edn). West Sussex: Routledge.

Cameron, C., and Moss, P. (eds) (2011) Social Pedagogy and Working with Children and Young People: Where Care and Education Meet. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Chamberlayne, P., Bornat, J., and Wengraf, T. (2000) The Turn to Biographical Methods in Social Science: Comparative Issues and Examples. London: Routledge.

Clarke, M. (2003) ‘Fit to Practice: The Education of Professionals’, Irish Association of Social Care Educators Conference (pp. 1-9). Cork: IASCE.

Curtice, M.J. and Exworthy, T. (2010) ‘FREDA: A human rights-based approach to healthcare’, The Psychiatrist 34(4), April: 150-6.

Davies, P., Crook, P., and Murray, T. (2013) An Archaeology of Institutional Confinement: The Hyde Park Barracks, 1848-1886, Studies in Australasian Historical Archaeology Vol.4. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Digney, J. and Smart, M. (2014) ‘Doing Small Things with Great Kindness: The Role of Relationship, Kindness and Love in Understanding and Changing Behaviour; in N. Howard and D. Lyons, Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 60-72). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Egan, G. (2014) The Skilled Helper: A Problem-Management and Opportunity-Development Approach to Helping (10th edn). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning.

Featherstone, B., White, S. and Morris, K. (2014) Re-imagining Child Protection: Towards Humane Social Work with Families. Bristol: Policy Press.

Fenton, M. (2014) ‘The Impossible Task: Which Wolf will Win?’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons (eds), Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 48-59). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Garfat, T. (2004) ‘New arrivals: Honeymoons and explorations’, Online Journal of the International Child and Youth Care Network. Available at <http://www.cyc-net.org/cyc-online/cycol-1004-honeymoon.html>.

Garfat, T. (2008) ‘The Inter-personal Inbetween: An Exploration of Relational Child and Youth Care Practice’ in G. Bellefeuille and F. Ricks (eds), Standing on the Precipice: Inquiry into the Creative Potential of Child and Youth Care Practice. Alberta: MacEwan Press.

Garfat, T. and Fulcher, L. (2012) ‘Characteristics of a Relational Child and Youth Care Worker’ in T. Garfat and L. Fulcher (eds), Child Youth Care in Practice (pp. 5-24). Cape Town: CYC-net Press.

Ghate, D. and McDermid, S. (2016) Implementing Head, Heart, Hands: Evaluation of the Implementation Process of a Development Programme to Introduce Social Pedagogy into Foster Care in England and Scotland. Loughborough: Colebrooke Centre and Loughborough University.

Hicks, D. and Beaudry, M. C. (eds) (2010) The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hingley-Jones, H. and Ruch, G. (2016) ‘Stumbling through’? Relationship-based social work practice in austere times’, Journal of Social Work Practice 30(3): 235-48.

HIQA (Health Information and Quality Authority) (2019) Guidance on a Human Rights-based Approach in Health and Social Care Services. Dublin: HIQA.

Howard, N. and Lyons, D. (2014) (Eds). Social Care Learning from Practice. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Johnson, M. (1987) The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Kennefick, P. (2006) ‘Aspects of Personal Development’ in T. O’Connor and M. Murphy (eds), Social Care in Ireland: Theory, Policy and Practice. Cork: CIT Press.

King, K. (2014) ‘There’s no Place Like Home: Care and Aftercare’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons, Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 37-47). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Kroll, B. (2010) ‘Only Connect … Building Relationships with Hard-to-Reach People: Establishing Rapport with Drug-Misusing Parents and their Children’ in G. Ruch, A. Ward and D. Turney (eds), Relationship- Based Social Work: Getting to the Heart of Practice (pp. 69-84). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Lalor, K. and Share, P. (2009) ‘Understanding Social Care’ in P. Share, & K. Lalor (eds) Applied Social Care An Introduction for Students in Ireland 2nd Edition (pp. 3-20). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell. Lyons, D. (2007) ‘Just Bring Your Self’, unpublished MA thesis, Dublin Institute of Technology.

Lyons, D. (2009) ‘Just Bring Your Self: Exploring the Importance of Self-awareness Training in Social Care Education’ in P. Share and K. Lalor (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Lyons, D. (2013) ‘Learn about Your Self before You Work with Others’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Lyons, D. (2017) ‘Social Care Workers in Ireland: Drawing on Diverse Representations and Experiences’, PhD thesis, University College Cork. Available at <https://cora.ucc.ie/handle/10468/5530>.

Lyons, D. and Reilly, N. (forthcoming) The SKIP Model: Social Care Knowledge Informing Practice. (publication planned 2022).

McCormack, B., Kitson, A., Harvey, G., Rycroft-Malone, J., Titchen, A. and Seers, K. (2002) ‘Getting evidence into practice: The meaning of “context”’, Journal of Advanced Nursing 38(1): 94-104.

McDowell, L. (1996) ‘Spatialising Feminism: Geographical Perspectives’ in N. Duncan, (eds) Bodyspace: Destabilizing Geographies of Gender and Sexuality (pp. 28-44). London: Routledge Publishers.

McHugh, J. and Meenan, D. (2013) ‘Residential Child Care’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds) Applied Social Studies: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (3rd edn) (pp. 243-58). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

McMahon, L. (2010) ‘Long-Term Complex Relationships’ in G. Ruch, A. Ward and D. Turney (eds), Relationship-Based Social Work: Getting to the Heart of Practice (pp. 148-63). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (2012) The Phenomenology of Perception, translated and edited by D. A. Landes. London/New York: Routledge.

Newman, B. M. and Newman, P. R. (2012) Development Through Life: A Psychosocial Approach. United Kingdom: Cengage Learning Products.

Ormond, P. (2014) ‘Thoughts on the Good Enough Worker’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons (eds), Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 251-63). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Payne, M., Adams, R. and Dominelle, L. (2009) ‘On Being Critical in Social Work’ in R. Adams, L. Dominelle, and M. Payne (eds) Critical Practice in Social Work (2nd edn). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Petrie, P., Boddy, J., Cameron, C., Wigfall, V. and Simon, A. (2006) Working with Children in Care: European Perspectives. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Stephens, P. (2013) ‘Social pedagogy: Heart and head’, Studies in Comparative Social Pedagogies and International Social Work and Social Policy Vol. XXIV.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Trevithick, P. (2003) ‘Effective relationship-based practice: A theoretical exploration’, Journal of Social Work Practice 17(2): 163-76.

Tuan, Y.-F. (2012) ‘Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective’ in S. Gale and G. Olsson (eds), Philosophy in Geography (pp. 387-427). London: D. Reidel.

Wenger, E. (2010) ‘Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of a Concept’ in C. Blackmore, Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice. New York: Springer Verlag and the Open University.

Wilson, K., Ruch, G., Lymbery, M. and Cooper, A. (eds) (2011) Social Work: An Introduction to Contemporary Practice. Harrow: Pearson.

Woodward, I. (2007) Understanding Material Culture. London: Sage.