Chapter 72 – Denise Lyons (D5SOP11)

Domain 5 Standard of Proficiency 11

Be able to analyse activity and adapt environments to enhance participation and engagement in meaningful life experiences and positively influence the health, well-being and function of individuals, families, groups and communities in their everyday activities, roles and lives.

|

KEY TERMS Heart, head and hands Meaningful life experiences Everyday activities Participation and engagement Environments and contexts of care

|

Social care is … a relationship, a psychological space between people, where they can grow, have their needs met, can learn to trust, feel accepted and heard. It is a privilege to work with people, especially at a time in a person’s life when they are defined by society as ‘vulnerable’. It is our job to bring kindness and our humanity to our interactions with others, without judgement or bias. Social care is very challenging because of the daily demands to be both personal and professional, to reflect and be present and to bring love and kindness to the people we have the pleasure to encounter in our working lives. |

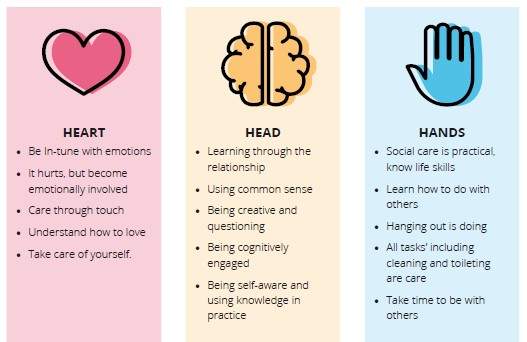

Social care practice has developed from individual service provision to organisations providing care and support for families, groups and communities. This standard of proficiency highlights the core of social care practice; that workers can focus their practice and adapt the environment to promote a person’s participation in meaningful moments and experiences. Creating environments that enhance participation and engagement requires us to adopt a holistic approach, which I have framed in a model for social care work entitled ‘Heart, Head and Hands’. This model is based on the findings from my PhD research (Lyons 2017) illustrated below, which uses Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi’s famous trinity of ‘head, heart and hands’ (Brühlmeier 2010) and incorporates ideas of contemporary theorists from practice in Ireland, Scotland and Canada (Doyle & Lalor 2009, 2013; Smith 2009, 2012; Garfat 2008; Garfat & Fulcher 2012; Digney & Smart 2014). The ‘heart, head and hands’ approach to social care practice presents the heart first, emphasising that all practice is contained within the relationship between the worker and the other (Lyons 2017). The ‘heart’ of the model outlines the values and attitudes needed to focus your practice on enhancing the service user’s participation and engagement in meaningful life experiences. The ‘head’ denotes all the knowledge underpinning this proficiency, including the key themes of this chapter, meaningful life experiences, everyday activities, participation and engagement, and contexts of care. ‘Hands’ relates to the practical activities and interventions that, when performed with care and respect, can ‘positively influence the health, well-being and function of individuals, families, groups and communities in their everyday activities, roles and lives’ (SCWRB 2017: 9).

Heart, Head and Hands – These are the main themes that emerged from my PhD research (Lyons 2017) on what social care workers ‘do with others’ in a variety of Irish social care settings.

TASK 1

Read Chapter 6 (‘Doing Small Things with Great Kindness’, by John Digney and Max Smart) in Howard and Lyons’ Social Care: Learning from Practice). Compare Figure 6.1 on page 64 of the book with the themes in the illustration above.

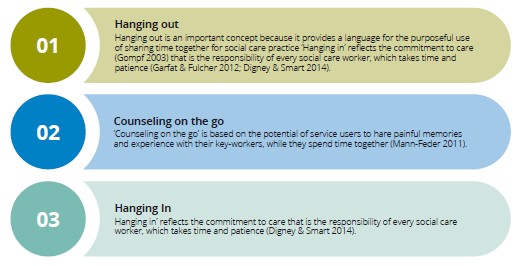

The ‘hands’, or doing stage, reflects how care is viewed as a verb, an action word, and what we do with others. These hands-on activities include day-to-day tasks, ‘direct care tasks’ (Fulcher & Ainsworth 2012), rituals of everyday life (Smith et al. 2013), and everything we do with people. They all involve one person engaging with another while they are doing things together and being with each other. We engage in activities, provide care and meet needs through the relationship (McHugh & Meenan 2009, 2013; Burton 2015). The relationship between a worker and service user is meaningful (Digney & Smart 2014), and trusting (Ruch et al. 2010; Howard & Lyons 2014). The relationship is the ‘core’ of practice that enhances the services user’s daily life experiences, supporting their increased participation in the community and enhanced health and wellbeing (Kennefick 2006; Lyons 2009). We cannot support a service user to engage in meaningful experiences and purposeful activities without first getting to know them, through being in a relationship. Garfat theorised this experience of being in a relationship with others through the terms ‘hanging out’ (spending time doing ‘normal’ things together), ‘hanging in’ and ‘counselling on the go’ (Garfat & Fulcher 2012).

Through hanging in, hanging out and counselling on the go, social care workers learn the likes, dislikes and needs of the service user, in order to communicate, advocate and engage. Using the relationship in this way enables workers to act as a bridge between the service user, other professionals and the community, where social care workers can effectively advocate and communicate these needs. The relationship is what makes social care work distinctive; it is the most important learning space for practice. As discussed, engaging in activity with services users also includes daily tasks that can enhance their overall health and wellbeing, which includes physical and intimate care tasks.

Physical and Intimate Care Tasks for Health and Wellbeing

Social care workers engage in caring for the physical and intimate needs of others (Carnaby & Cambridge 2005), thus promoting and supporting the health and wellbeing of service users. This can include the manual handling tasks of lifting, using hoists, pushing wheelchairs, and moving furniture and aids. Many students find providing for the physical and intimate care needs of service users difficult, and this is viewed as one of the main deterrents to taking up a career in the disability sector. Personal care tasks include shaving, skin care or applying external medication, hair care, help with feeding, teeth care, undressing and dressing, applying makeup and deodorant, and prompting to go to the toilet or bathroom (Twigg 2000). Intimate care duties, by virtue of the title, are more personal and include dressing and undressing (underwear), helping someone use the toilet, changing soiled incontinence pads, bathing and showering, washing intimate body parts, menstrual care, administering enemas, and administering rectal medication (Carnaby & Cambridge 2006). When providing intimate care, it is essential that the space is adapted to ensure that a person’s dignity is protected (Twigg 2000). In all care duties, the social care worker is trying to ensure that intimate experiences feel respectful and private and are performed with dignity. There may be opportunities to provide meaningful moments while brushing someone’s hair or while patiently supporting an individual to select what they want to wear that day. As social care workers, we use daily events within our planned practice to enhance a person’s involvement in experiences that are beneficial and meaningful to them.

TASK 2

Describe a recent experience that was meaningful for you in your life. Why was this experience important?

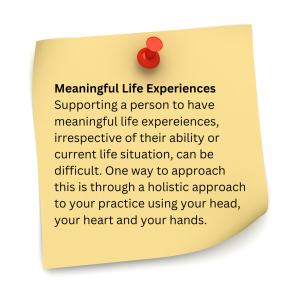

Meaningful Life Experiences

Activities can provide opportunities to enhance the relationship and create meaningful moments within day-to-day shared life events. Having a meaningful experience is tied to having a sense of purpose, feeling productive and needed, having a satisfying social network, and a sense of belonging within close reciprocated relationships. We use the head when we are actively involved in the work of social care and facilitate meaning- making through mutual engagement and doing things together within the relationship. This is purposeful practice, based on an integration of the theories that underpin the work and experiences that inform and shape it. When we have a relationship with another person, we work from the heart, showing care and kindness, unconditional positive regard and empathy.

Everyday Activities

Getting to know a person enables you to learn about their likes and dislikes, what activities they enjoy, who they like to spend time with and what experiences are meaningful for them. Engaging in different activities can play a significant role in relationship development and the creation of meaningful moments. Social care is viewed as a hands-on role, where workers ‘do’ with others, though being together (Digney & Smart 2014).

Participation and Engagement

Like us, the people in our care are social beings who need to be provided with opportunities for fully participating and having a meaningful engagement with the world around them. One place to start is within the local community. Walking is an important activity for community engagement and social learning, where people can get to know others external to the service and find out what local services are available to them. Walking in the local neighbourhood is part of travel training for people with a disability, and in the HSE’s New Directions report is viewed as one of the ways to achieve community engagement (HSE 2012). Getting out in the community emerged within the ethos of the normalisation of public and private spaces for the care of people, thus helping to recreate the space from the institution to the home. Social care workers do not always need to look beyond the service to promote participation and engagement; the service itself or ‘context of care’, with imagination and in collaboration with the service user, can also facilitate meaningful moments. The office can be viewed as a ‘staff only’ space, which can give the impression of spaces in a person’s home that the service users are not permitted to enter. It is important to maintain a balance between the confidential storage of important information and the office documents and some space for the residents to sit and chat.

Adapting Environments – Creating a Home

Practice settings are the places and spaces that service users and workers inhabit which are flexible and adapted to meet diverse needs and practices. The question of ‘where social care work happens’ is complicated, as it includes the physical building or social care service and relevant social care spaces, which can include, but are not exclusive to, the kitchen, the office, the car, the coffee shop, the bathroom. Social care services are either a residential or day service, which is adapted to become an activity centre, a place for work and/or activity, treatment, care and love, and a person’s home (Byrne 2016). Specific spaces are also purposefully used and adapted to enhance the service user’s feeling of belonging and active participation.

TASK 3

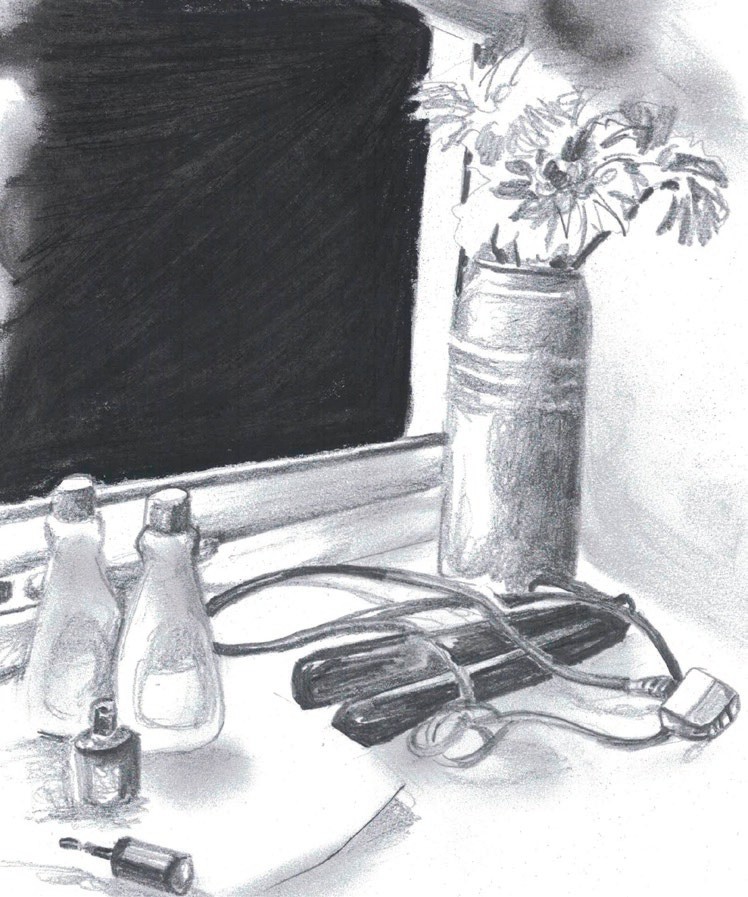

This is the bedroom window sill in a residential home for adults. Who lives here? Why did you come to that conclusion?

As well as being a practical base for the provision of care, spaces within the service can also evoke feelings of being welcome, or feeling at home. The service is the physical representation of how practice is influenced by policy, and valued by society.

Creating a Home: Social care workers often adapt a room or house as a space where meaningful life experiences happen on a daily basis in a place that is personalised, lived in and loved. Trying to recreate the experience of home in an unnatural setting is a difficult task, especially as there is limited scope within practice to discuss the meaning of home for both workers and service users. The idea of creating a homely space for people to live has become a national standard in all government publications on residential care since 2004: ‘it should be as much like an ordinary family home as possible’ (DoHC 2004: 31). Cooper (1974: 131) described ‘home’ as a personal space where we have control over the ‘few intimates that we invite into this, our house’, especially the people we live with. In reality, service users have limited control over the people invited to live, to visit, or work, in the space (HSE 2011). The appropriate placement of residents together in the one house is paramount, as it can be very destructive to a resident’s placement if they do not get along with the other residents (Reynolds 2014). Having your own bedroom in the house can also increase the sense of home. The physical house is also viewed as an expression of self: ‘we project something of ourselves onto its physical fabric’ (Cooper 1974: 131). The expression of self is manifest in the material culture of the space including furniture, the way it is placed around the room, the selection of photographs and images hung on the walls (Woodward 2007). In residential services, service users may have limited involvement in the purchasing and placement of furniture and personal items in the house other than in their own bedroom.

The desire to create a homely atmosphere is aided through rituals and social practices, for example making a cup of tea for people when they arrive at a day service or sharing a cup of coffee and a chat during the day in a residential house (Martin & Rogers 2004). Byrne (2016) discusses how staff used the cup of tea both as a way of engaging with the service users and also as a way of alleviating stress during the day; taking a break and having a cup of tea. This is most common for residential care staff who are not permitted to take a break away from the unit. Making tea is also a ritual between the staff members, where team meetings can evoke feelings of family and engagement, by starting with a cup of tea (Martin & Rogers 2004). Staff members can also feel more at home if the management creates a culture and atmosphere of respect where individual opinions are heard (Martin & Rogers 2004), in the negotiation of practice (Wenger 2010). (Drawing by Denise Lyons)

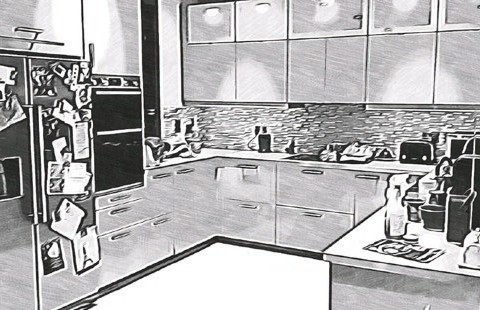

The kitchen, the heart of most social care services, can become a space for meaningful connections and experiences. This room plays a central role in ordinary family life but also in the lives of service users and social care workers. As well as the place designated for eating, the kitchen is also the room where people gather to perform everyday activities and do one-to-one work. In the home, families eat around the kitchen table, and this practice is viewed as part of normalisation in service provision. The kitchen is also a space where gender roles are practised, learned and adopted (Byrne 2016). It is important for social care workers to examine what practices exist within their service to ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to engage, when possible and appropriate, in the preparation of food.

The kitchen is a place where service users can express personal choice by having some input and participation in the menu and the food that is prepared there. The kitchen table is also a place for communication and relationship development, providing a focal point for a relaxed and non-threatening discussion. As well as the place designated for eating, the kitchen is also the room where people gather to perform activities, for example doing homework, playing board games and doing art. (Photograph by Denise Lyons)

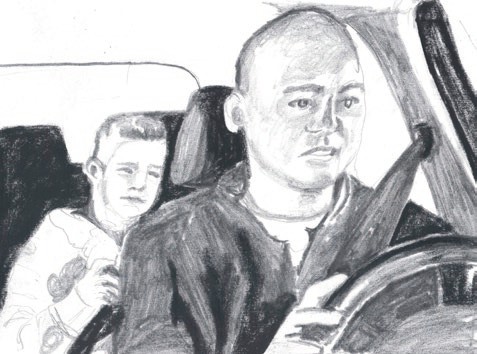

The car: The car has become so necessary for social care work that many organisations list having a full driving licence as a prerequisite for employment (Ferguson 2009). The car can be an expression of care and humanity, through the act of collecting and bringing someone where they need to go (Miller 2001). As well as being used to bring people to their destination, for example to school or on an access visit, the car is also a space for purposeful relationship-based work. There are three factors that facilitate the role of the car for purposeful social care work.

First, the reason for the journey (Ferguson 2009); second, being in the confined space of the car and moving between fixed spaces creates a pause in ordinary life; and finally, the arrangement of the car seats creates a physical space between the passengers, including the avoidance of direct eye-contact (Ferguson 2010). (Drawing by Denise Lyons)

Ross et al. (2009) explain how relationship-based social care work can become framed and bounded within the car. Sitting within the physical boundary of the car made young people feel safe, and this feeling encouraged them to share and have intimate ‘car conversations’ (Ferguson 2009). Ross et al. (2009: 612) described these ‘car conservations’ as free-flowing, ‘offering a means through which young people could share past memories, associations, and future imaginings that the journey brought to mind’. The drawing above represents people engaged in a ‘car conversation’. The worker is looking forward, and the lack of eye contact enables the young person to chat freely. The car can encourage the service user to leave the centre and get out into the community.

The community: Getting out and doing shared activities together outside is an important part of the shared experiences of social care work (Fulcher & Ainsworth 2012). Eating out in the community is an important social activity for people with an intellectual disability (Adolfsson et al. 2010). However, this activity may be limited based on multiple possible factors, for example: the unsuitability of the space for people with a disability; any behaviours of the service users that challenge; specific food allergies or requiring food liquidised or thickened (Adolfsson et al. 2010). Ross et al. (2009) mention the role of walking as an important activity for community engagement and social learning. Walking in the local neighbourhood is part of travel training for people with a disability, and is viewed a way of achieving community engagement (HSE 2012). Getting out in the community emerged within the ethos of the normalisation of public and private spaces for the care of people, from the institution to the home. Another way of getting out and about is through the use of the car, which, as we have seen, can also become a space for purposeful practice and meaningful experiences.

To understand social care is to acknowledge that the meaningful moments we achieve for individuals, groups and the community are shaped by the breadth, depth and complexity of practice. Of the many theoretical frameworks contained within this book, this chapter introduces the ‘Heart, Head and Hands’ model to capture an experience that is relational, emotional, caring, physical, and experienced within the physical environments or contexts of care.

![]() Tips for Practice Educators

Tips for Practice Educators

As discussed, meaningful moments can happen during the ordinary shared experiences between the service user and the student. Students need time with the service users to develop relationships and learn about the individual’s or group members’ likes and dislikes.

Beginning of placement: Where possible, give the student specific tasks in the commonly used rooms in your service, for example the kitchen. Loading and unloading the dishwasher enables the student to start casual conversations and observe service users’ different drinks and food preferences. Encourage the student to invite service users for tea and a chat, when they can get to know each other better.

Middle of placement: This is the time for the student to introduce activities that will appeal to the service users and will offer them alternative experiences and opportunities. For ideas on creative activities, go to Chapter 75, but here are a few to get you started:

a. Look at communal spaces – do they reflect the people living or working there? What about doing a photo collage of shared memories between the staff and the service users to hang on the wall?

b. No place like home – show the service users and staff photographs of different rooms on Pinterest, and ask them to select the room that feels most like home. Look at simple ways you could use these ideas to make the communal spaces feel more like home to everyone who lives there.

c. Create photo albums with individual service users of their likes and dislikes, meaningful people and places.

d. Make individual ‘memory maps’ of all the local services that you can visit together.Make a space in the day for everyone to sit, drink tea and share their ‘meaningful moment of the day’ story.

References

Adolfsson, P., Sydner, Y.M. and Fjellström, C. (2010) ‘Social aspects of eating events among people with intellectual disability in community living’ Intellectual and Developmental Disability 35(4): 259-67.

Burton, J. (2015) Leading Good Care: The Task, Heart and Art of Managing Social Care. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Brühlmeier, A. (2010) Head, Heart and Hand: Education in the Spirit of Pestalozzi (Translated by Mike Mitchell). Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

Byrne, D. (2016) ‘Governance of the table: Regulation of food and eating practices in residential care for young people’, Administration 64(2): 85-108.

Carnaby, S. and Cambridge, P. (eds) (2005) Person-Centred Planning and Care Management with People with Learning Disabilities. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Cambridge, P., & Carnaby, S. (2006) Intimate and Personal Care with People with Learning Disabilities. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Cooper, C. (1974) ‘The House as Symbol of the Self’ in L. Lang (ed.), Designing for Human Behavior (pp. 130-46). Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson and Ross.

DoHC (Department of Health and Children) (2004) The National Standards for Residential Care for Young People. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Digney, J. and Smart, M. (2014) ‘Doing Small Things with Great Kindness: The Role of Relationship, Kindness and Love in Understanding and Changing Behaviour’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons, Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 60-72). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Doyle, J. and Lalor, K. (2009, 2013) ‘The Social Care Practice Placement: A College Perspective’ in P. Share and K. Lalor, Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (2nd edn; 3rd edn),

pp. 165-81; 151-66. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Ferguson, H. (2009) ‘Driven to care: The car, automobility and social work’, Mobilities 4(2): 275-93.

Ferguson, H. (2010) ‘Therapeutic journeys: The car as a vehicle for working with children and families and theorising practice’, Social Work Practice 24(2): 121-38.

Fulcher, L. and Ainsworth, F. (eds) (2012) Group Care Practice with Children and Young People Revisited. New York: Routledge.

Garfat, T. (2008) ‘The Inter-personal Inbetween: An Exploration of Relational Child and Youth Care Practice’ in G. Bellefeuille and F. Ricks (eds), Standing on the Precipice: Inquiry into the Creative Potential of Child and Youth Care Practice. Alberta: MacEwan Press.

Garfat, T. and Fulcher, L. (2012) ‘Characteristics of a Relational Child and Youth Care Worker’ in T. Garfat and L. Fulcher (eds), Child Youth Care in Practice (pp. 5-24). Cape Town: CYC-net Press. Howard, N. and Lyons, D. (eds) (2014) Social Care: Learning from Practice. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

HSE (Health Service Executive) (2011) Time to Move on from Congregated Settings: A Strategy for Community Inclusion. Dublin: HSE.

HSE (Health Service Executive) (2012) New Directions: Review of the HSE Day Services and Implementation Plan 2012-2016, Personal Support Services for Adults with Disabilities Working Group Report. Dublin: HSE.

Kennefick, P. (2006) ‘Aspects of Personal Development’ in T. O’Connor and M. Murphy (eds), Social Care in Ireland: Theory, Policy and Practice. Cork: CIT Press.

Lyons, D. (2009) ‘Exploring the Importance of Self-Awareness Training in Social Care Education’ in P. Share and K. Lalor (eds), Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (2nd edn) (pp. 122- 36). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Lyons, D. (2017) ‘Social Care Workers in Ireland – Drawing on Diverse Representations and Experiences’. PhD thesis, University College Cork.

Martin, V. and Rogers, A.M. (2004) Leading Interprofessional Teams in Health and Social Care. New York: Routledge.

Miller, D. (2001) Car Cultures. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

McHugh, J. and Meenan, D. (2009, 2013) ‘Residential Child Care’ in P. Share and K. Lalor (eds), Applied Social Studies: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (2nd edn; 3rd edn) (pp. 291-304; pp. 243-58). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

Reynolds, N. (2014) ‘A House for One: Single-occupancy Residential Units’ in N. Howard and D. Lyons, Social Care: Learning from Practice (pp. 185-96). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Ross, N.J., Renold, E., Holland, S. and Hillman, A. (2009) ‘Moving stories: Using mobile methods to explore the everyday lives of young people in public care’, Qualitative Research 9(5) 605-23.

Ruch, G., Ward, A. and Turney, D. (eds) (2010) Relationship-Based Social Work: Getting to the Heart of Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Smith, M. (2009) ‘Social Pedagogy’ in The Encyclopaedia of Informal Education. Available at <http://infed. org/mobi/social-pedagogy-the-development-of-theory-and-practice/> [accessed 17 October 2016].

Smith, M. (2012) ‘Social pedagogy from a Scottish perspective’, International Journal of Social Pedagogy 1(1): 46-55. Available at <https:internationaljournalofsocialpedagogy.com>.

Smith, M., Fulcher, L. and Doran, P. (2013) Residential Child Care in Practice: Making a Difference. Bristol: Policy Press.

Social Care Workers Registration Board (2017) Standards of proficiency for social care work. Dublin: CORU Health and Social Care Regulator.

Twigg, J. (2000) Bathing: The Body and Community Care. New York: Routledge.

Wenger, E. (2010) ‘Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of a Concept’ in C. Blackmore, Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice. New York: Springer-Verlag and Open University.

Woodward, I. (2007) Understanding Material Culture. London: Sage.