Chapter 79 – Gillian Larkin (D5SOP18)

Domain 5 Standard of Proficiency 18

Know the basic principles of effective teaching and learning, mentoring and supervision

|

KEY TERMS Teaching Supporting On-going learning Continuous professional development

|

Social care is … about working with people with various difficulties and issues in partnership to find the right support so they can live empowering independent lives. |

According to McSweeney and Williams (2018), social care practice encompasses knowledge from disciplines such as psychology, sociology, human rights in addition to the use of evidence-based practice. As well as an extensive knowledge base, social care workers require an array of skills including communication, active listening, boundary management, assessments, interventions (Allen & Langford 2008), while values of human rights, anti-discrimination, anti-oppression, empowerment, social justice, and equality provide the context in which we work (Lalor & Share 2013). In practice, this could mean working with several service users at the one time, all with different needs, utilising a range of skills and knowledge specific to each person so that their care is person-centred to them. In addition, social care workers need to work in and understand the legislative and policy framework of the organisation in an often changing environment. In my experience, social care professionals work under conditions of complexity and uncertainty and require a combination of theory and skills to deliver safe, effective, and efficient person-centred care (Turpin, Lynch & Spearmon 2015; Lalor & Share 2013).

Developing and maintaining these skills, values and knowledge is challenging due to the evolving nature of social care development, the ever-expanding evidence base, and caring for service users with often-complex social and emotional needs. Consequently, social care staff, whether in the learning, graduate or experienced phase of their career, are all learners.

TASK 1

Think about…We can all remember those times when we experienced being new to a situation: first day at school, first day on placement, and the first week of taking up a new post in a social care setting.

Take a moment to think back to how it actually felt to be a student on placement/a new member of staff.

- What are some of the main issues you think your students/graduate staff members/new experienced staff might be facing being in a new work environment?

- What might you as a social care worker do to help them?

The Multiple Roles of a Social Care Worker

A social care worker does not focus on just the service user, but on students who are undergoing their placement, on graduate social care workers, on peers and on the self. This means a social care worker could be supporting a student on placement, mentoring a colleague, acting as a supervisor to colleagues and engaging as a student as they continue in their professional development. Therefore, social care workers are teaching others and learning through their interactions with students and staff, through supervision, mentoring and personal development.

An On-Going Learning Journey

Social care students receive training to prepare them to work in such a diverse field, both in the classroom and out in the practice environment through student placements. Within the education setting syllabi, student handbooks, assessments, evaluations and tests provided to the student ascertain their understanding and development. This learning process provides various guidelines and clear expectations, and when a student struggles to meet expectations there are supportive steps and interventions. Students receive a continuation of their social care education in practice placement. It is here where students apply theoretical knowledge and proficiencies, develop their practice skills and professional values, understand the working of a social care organisation and become more aware of themselves and their learning needs, through supervised participation in the work of a social care agency (IASCE 2009).

Once qualified, social care workers engage in Continual Professional Development (CPD). The Health and Social Care Council define CPD as “the means by which health and social care professionals maintain and improve their knowledge, skills and competence, and develop professional qualities required throughout their professional life” (CORU 2013). CPD can include different activities; Mary has recently trained as a Practice Educator while Lukas has attended a conference on Resilience in Children, and Francis is undergoing Key Worker training.

Teaching and Learning

Teaching is an important part of the professional’s role and members of the social care profession teach students and other staff at some point in their career. Teaching involves setting appropriate learning experiences and includes activities/opportunities or kinds of interactions that lead to learning new information, skills and ways of thinking and being (Taylor & Hamdy 2013).

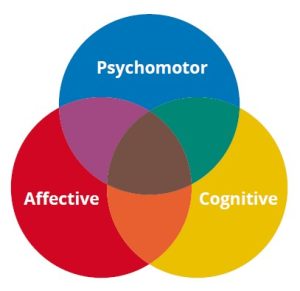

Within social care, learning can occur in many ways. Jarvis (1983 cited in Hand 2006: 3) suggests learning can occur “…via the acquisition of knowledge, skills or attitude by study (course, training), experience (applying the theory/working with service users) or teaching (practice educator/supervisor/mentor)”. Reece and Walker (2007) note there are three domains of learning: cognitive, affective and psychomotor (behaviour), and learning can occur from teaching, study or the assimilation of information and skills from experience.

The three domains of learning take place along a continuum and the more learning, practice and experience a student/worker has the higher levels of learning that occurs (see table below).

|

Cognitive Domain – think |

Examples from Social Care Practice |

|

Learning takes place across the six levels – knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation |

A student has knowledge of Children’s First Guidance (2017) prior to going on placement. In placement the student is asked to apply the legislation to a situation; a student may be asked to evaluate the effectiveness of the legislation. |

|

Affective Domain – feelings/emotions |

Examples from Social Care Practice |

|

Concerned with attitudes, values, beliefs, opinions, interests and motivations Learning takes place across the six levels – receiving phenomena, responding to phenomena, valuing, organisation, internalising value |

Learning activities aim to develop students’/ workers affective skills. For example – learning about discrimination helps students challenge existing views and opinions and incorporate new values within their existing value base. Students move from learning about a new concept to internalising it into their behaviour through practice, experience and further opportunities for learning. |

|

Psychomotor/Behavioural Domain – doing |

Examples from Social Care Practice |

|

Psychomotor skills relate to the ability to convert the basic skills of knowledge and attitude into physical skills and hands-on applied and technical proficiencies related to movement, coordination and practices. Learning takes place across six levels – perception, set, guided response, mechanism, complex overt response, adaptation, origination. |

Learning activities aim to develop students’/ workers behavioural skills through observing and copying to develop skills. For example, students become aware of the importance of body language as a form of communication and develop through imitation/ practice skills in identifying eye contact, body posture, gestures and facial expressions and learn until the skill is automatic, integrated into practice and adapted to different service users/ situations. |

Source (Randall 2011)[1]

While learning is often associated predominately with cognitive learning, practice educators and mentors however must teach more than just knowledge and should guide students toward development within the affective and psychomotor domains, and in essence, the domains are often interrelated (Hoque 2017). Some examples may help in understanding how the learning occurs.

Case Study 1

As an academic tutor I was on a placement visit and a student was telling me about her interaction with a service user who was attending a course in parenting support. The service user was not engaging with the student and her body language was closed off. The student remarked she found the service user challenging due to the lack of engagement and was quite impatient with her. In discussion the student demonstrated her understanding of the theory (cognitive domain) and her skills in reading body language (psychomotor domain) however the student had not demonstrated an unconditional regard (Rogers 1957) for the service user and was judgemental in the lack of engagement by the service user. The student did not demonstrate the correct attitude or professional manner (affective domain), so this proficiency was not met.

Case Study 2

Student Princess was working with a young woman, Clare, who was seeking a job and had sought help to do up her CV. Clare had Spina bifida and experienced some paralysis in the lower part of her body so used a wheelchair. Princess was delighted to help her and typed up the CV. At supervision Jackie (practice educator) asked Princess to reflect on how the activity went. Princess felt it went very well as the task was completed. Jackie asked Princess if she could explain (cognitive domain) the ethos of the service. Princess was able to explain that the service was underpinned by an empowerment model. When asked to apply it to practice, she said it was empowering service users to do things and make choices for themselves (cognitive domain). Princess was asked did she empower Clare and she said yes. However, Jackie asked Princess to delve deeper into her practice and asked her “Did you asked Clare what help she needed?” “Did you let Clare take the lead in the task?” In discussion Princess learned that while her intentions were good, she had not valued Clare as an independent woman but rather her engagement with her was based on her belief (affective domain) people with disabilities cannot do or think for themselves. This supervision session enabled Jackie to teach Princess about her knowledge and beliefs via cognitive and affection domain learning.

Types of Learning

The European Commission (2001, cited in UNESCO 2009) has drawn attention to different kinds of learning, and have identified a typology of learning. This is of relevance to all social care students and professionals as it offers a lens through which we can determine what way we are learning.

Rogers (2014) considers the notion of formal learning, which is intentional, structured, occurs in an education institution and leads to certification. This type of learning mirrors the educative and practice placement opportunities students engage in, and the CPD activities the professionals undertake.

Non-formal learning is also organised, intentional, certified and can include first aid training, SAMS training, report writing training and so on. A third type is Informal learning and results from daily life activities related to work, family or leisure. In most cases, it is non-intentional and frequently unconscious (UNESCO 2009: 27). Tannenbaum et al. (2013, 2010 cited in Cerasoli et al. 2017) believes once formal training has finished employees are provided with the potential for informal learning from their working environment. For example, I learned about Transactional Analysis (TA) and developed the skill of negotiation while working in practice.

Think about…

Have you learned a new theory, piece of legislation, model of practice while on placement or in work?

What new skills have you learned as a result of your placement or work?

Did you require support with your new learning?

Who offered you support?

Student-Centred Learning (SCL)

The notion of teaching and learning has moved from a teacher led style to a more student-centred approach. Harden and Crosby (2000: 335 cited O’ Neill & McMahon 2005) describe teacher-centred learning strategies as the focus on the teacher transmitting knowledge, from the expert to the novice. In other words, the teacher is the driver of learning, and does not provide choice to the student in terms of what or how they want to learn. Conversely, a student-centred approach focuses on the principles outlined below and promotes a more collaborative process between the teacher and learner and one that is used within the social care environment:

Figure 1.2: Principles of Student-Centred Learning (O’Neill & McMahon 2005)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exploring the Multiple Roles of a Social Care Worker

Practice Educator

The Practice Educator is a member of the social care team who works with a student to maximise learning on practice placement. This includes identifying learning objectives, monitoring their learning, engaging in supervision sessions and assessing student development in conjunction with the student’s education provider. Through participation in this learning environment, students integrate theory based learning with the realities of practice and through which professional competence is achieved (Alsop & Ryan 1996). In effect, Davys and Beddoe (2000) note the role essentially involves managing, assessing, monitoring, teaching, challenging and supporting the student. What a hugely important role practice educators provide to the social care sector. As articulated by McSweeney (2016), practice educators are essential in the education of social care workers.

Stop!

Are you a Practice Educator?

If yes, give yourself a huge clap. You are an essential part of social care learning and development.

Do you work with a colleague who is a Practice Educator? Shout out well done, give them a clap, buy them a coffee and a scone – you choose!

Are you thinking of becoming a Practice Educator? Thank you!

We can all remember the time of being a student – the not knowing, of being unsure, of being afraid, of not being sure if we would make it! To my practice educators, to the practice educators of today and tomorrow – keep up the good work!

Bastable (2014) argues it is essential for a practice educator to have knowledge (of the material to be learned, the learner, the social context), and be competent (be imaginative, flexible, and able to employ teaching methods, display solid communication skills; and have the ability to motivate others) to facilitate effective learning with students. Thus, it is necessary for social care workers who take on the role of a practice educator to engage in ongoing professional development.

Learners as a Resource

A key learning opportunity is when students are on placement. Students bring new ideas and knowledge, can challenge practices for both the practice educator and other staff and prompt increases in the practice educator’s reflection (Mc Sweeney 2016). McAllister and Lincoln (2005: 1) found that practice education and the experience of having students offered “opportunities to both educators and students for professional growth” and that this professional growth and development implied a “movement along a continuum of professional skills and competencies”.

Examples from Student Placements

Student Fiona noted that first thing in the morning on placement, a staff member was tasked with waking up each service user at 8am regardless of whether they were going to school or Youthreach, which led to difficulties when the young people would not get up. Fiona asked if those not getting up for education could be left until those going to education had gone? In the team meeting, the staff remarked they had been doing the routine for so long, it was no longer fit for purpose, but no one thought to change it.

In a supervision session, a student explained the Social Role Valourisation Theory (Wolfensberger 1983) to the practice educator, who was engaging in such practice, but did not know the evidence base behind it. Another student provided a presentation on New Directions as the staff team were unfamiliar with the guidelines.

Supervision and Mentoring

To ensure a supportive teaching and learning environment, the ‘teacher’ needs to demonstrate a genuine non-threatening relationship with the ‘student’.

Bernard and Goodyear (2013: 7) define supervision as “an intervention provided by a more senior member of a profession to a more junior member or members of that same profession”, or in the case of a student placement, is provided by the practice educator to the student. Morrison (2003) proposes that the purpose of supervision is to enhance the social care worker’s/students professional skills, knowledge, and attitudes in order to achieve competency in providing quality care. Supervision is documented and thus is an evaluative process (Saliba 2013). The follow example demonstrates how supervision prevented a student from leaving her placement.

“It was my first week in placement and I was struggling. I had never worked with people with disabilities before and found I could not understand when they spoke to me, and one service user threw her bag at me because I kept saying ‘pardon, sorry, pardon’. At my first supervision I told my practice educator I was leaving as the service users did not like me and I cannot understand what they are saying. I was crying as I always wanted to be a social care worker but was rubbish! My practice educator was amazing. She let me say how I was feeling (affective domain) and then asked me to tell her all the interactions I had with service users that were positive. I struggled but named two. She explained to me that all students experience difficulty with service users initially and communication is a skill (psychomotor domain) I will develop during placement through practice. We discussed theory that would help me (cognitive domain), and we explored other reasons why the service user may have been cross (cognitive domain), and I identified 2 skills (psychomotor domain) that I wanted to achieve around communication before my next supervision session. We then discussed my feelings in regard to the service user being cross with me and how I attributed my inability in understanding the communication to being ‘stupid’ and my subsequent reaction. Through the discussion I learned that I had no awareness that I was valuing myself against my engagements with the service users, and when I perceived that things had not gone well, it was an indication of my lack of ability, which led to an overload of emotion. To try to increase my awareness around my feelings (affective domain) and what were triggers to feeling good, bad, confident etc. my practice educator asked me to journal my feelings on a daily basis with a view to helping me making connections between feelings and behaviour (Year 2 Social Care Student)[2].

Similar to supervision, Mentoring also involves two parties (a mentor and a mentee), a relationship (formal or informal), and the transfer of skills, knowledge and attitude with the objective of development growth of the mentee (Bilesamni 2011). Megginson and Clutterbuck (1995: 13) define Mentoring as “offline help by one person or another in making significant transitions in knowledge, work or thinking”. Unlike supervision, informal mentoring is not an evaluative process (Inzer & Crawford 2005).

Within social care mentors can be a peer or a senior member of staff who offer informal support to new graduates as they can experience a variety of developing challenges that may impact on competent practice, may feel inadequately prepared to practice independently, or navigate the complex responsibilities required. Taherian and Shekarchian (2008) note engaging with a mentor can help increase a mentee’s motivation and empower and encourage them which can raise the performance bar, while as a result of nurturing self-confidence, teaching by example and offering wise counsel mentors can experience higher levels of well-being and work satisfaction (Morgan & Rochford 2017).

The following examples demonstrates the difference between mentorship and supervision, and the role of evaluation.

Supervision Example

Martha is a supervisor for Anthony, a social care worker who has been on the team for three years. This is a very structured relationship. There are regular meetings that support Anthony around the three supervisory functions of education, support and accountability (Kardushian, 1992). During the most recent supervision session, Anthony talked about finding it difficult to work with one young person in the unit, as this young person’s behaviour had escalated and there is limited interaction with the staff team. As his key worker, Anthony felt he was not able to help the young person. He was feeling very low and a little angry as he had worked hard with the young person and felt the lack of engagement was a reflection on him, and really felt the young person ungrateful.

During this session, Martha asked Anthony to evaluate the young person’s behaviour from a theoretical basis (educative function) and reflect on why he was taking the young persons’ actions personally. Martha acknowledged the anger he is feeling and while supporting Anthony with his feelings (supportive function), highlighted this anger could seep out into his practice with the young person, which would be a boundary violation (Davidson 2005) (accountability function). Through discussion, Anthony said he was not sleeping well due to a new baby at home, and this was affecting his work. Martha spoke to Anthony around different options of self-care and invited Anthony to a further supervision meeting if needed. In line with regulations, Martha documents the supervision meeting.

Mentoring Example

Josephine has been mentoring new staff in the team for the last five years. She has fifteen years of social care experience and has worked in a variety of services before taking up her role in this service nine years ago. Josephine works informally with the new staff for a period of six months depending on the needs of the staff member. During this time, Josephine supports the new staff member to settle into the staff team, build relationships with all the stakeholders, offers feedback and provides new learning strategies, based on her knowledge and experience, to help the staff member become competent and confident in their practice. Josephine really enjoys this role as it allows the new staff to be open about their practice and seek support without being concerned of evaluation, as can be the case in a supervision meeting.

Tips for all Learners – What Helps Learning?

Roger’s (1957) discusses three core principles to facilitate a therapeutic change, that of congruence, empathy and unconditional positive regard. As learning is also about change, the right environment is essential to ensuring optimal development. Hand (2006) has outlined some characteristics as essential to supporting learning which fit nicely in our roles of teacher and learner:

- Listening and responding consistently

- Helping the ‘student’ to identify feelings and personal knowledge

- Sharing of self with the student

- Being sensitive to the students’ needs

- Valuing the learner as a person respecting and caring for his/her feelings and opinions

- Showing empathetic understanding

- Being aware of personal strengths and weaknesses and their effect on others

TASK 2

Activity:

Identify an element of your practice that you need support with and look around your staff team and select someone who you think may be able to help you.

Explain your issue and seek their help.

- How does it feel being the learner?

- Ask your colleague how it feels teaching you something new?

Case Study 3

Philip has recently graduated and is three months into his job as a social care worker and is finding things difficult. He loves the work and is really enjoying working with the young people but is not sure if he is doing the work ‘right’! All of the other staff seem so sure of themselves and know how to deal with all situations with the young people. Philip thinks he has made the wrong career choice. Philip has spoken to his mum and she has suggested he talks to his supervisor however, Philip was adamant he would say nothing as it would look like he was rubbish at his job, and he is on probation.

- What are the benefits of providing Philip with a mentor?

- What will be the mentor’s role?

Case Study 4

Sonia has been working in Cedar Family Support Services for three years and is struggling in her role. She has been working with the Byrne family for three months and is finding it difficult to separate her feelings to the mother Denise from her own personal experiences. On a number of occasions, she was quite judgemental towards Denise, and could not accept how she could forget to feed her children, and send them to school with no coat, to the point that five-year-old Sadie was hospitalised with a severe chest infection. Sonia could not contain her displeasure at those poor children experiencing neglect so asked a colleague to work with Denise last week; Sonia knows this is not a long-term option. Sonia’s supervisor has noticed she

is not engaging with her service user as she normally would and has asked to have a supervision session with her.

- What do you see as the issues Sonia is experiencing?

- In your opinion, does Sonia need a supervision or mentoring session? Please explain your choice.

Case Study 5

Sunita is preparing the schedule for her new social care student. Sunita has been a social care worker for six years and has extensive experience in supervising students. This is her fourth year as a Practice Educator. Sunita likes to engage in weekly supervision sessions with the student as this allows her to keep a check on student development, complete the college supervision logs and assess how the student is progressing in meeting the relevant proficiencies.

In preparing the schedule, Sunita provides opportunities that allows the student to develop in all areas including knowledge, legislation, models of care and application to practice. Both Sunita and the staff-team demonstrate ethical practice, skills in how to engage, communicate and work with service users, and develop reflection skills. Students are taught to be responsible and accountable for their decisions and actions through the allocation of roles and duties.

Supervision allows students to reflect on their practice and discuss areas that are going well for them and challenges that need support. In this space, students are given the time to talk about their emotions and feelings, their judgements and biases. In her role, Sunita offers the student constructive feedback on what has been observed by herself and colleagues in practice and this creates awareness and opportunities to enhance practice, feelings, emotions and skill development.

A key part of the practice educator role is to support the student to think critically and Sunita does this through asking questions and supporting the students to draw on many theories and skills to search for the most appropriate approach. Sunita also provides access to training such as report writing, Manual Handling, First Aid, SAMS and MAPPA.

- In your opinion, what other opportunities are there for Sunita to teach her student?

- Can you think of any opportunities where the student may be able to teach Sunita?

References

Allen, G. and Langford, D. (2008) Effective Interviewing in Social Work and Social Care: A Practical Guide. London: Palgrave McMillan.

Alsop, A. and Ryan, S. (1996) Making the Most of Fieldwork Education: A Practical Approach. London: Chapman & Hall.

Bastable, S. (2014) Nurse as Educator: Principles of Teaching and Learning for Nursing Practice (4th edn). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Bernard, J.M. and Goodyear, R.K. (2013) Fundamentals of Clinical Supervision (5th edn). Boston: Pearson.

Bilesanmi, B. (2011) ‘Mentoring: an emerging trend in the forefront of HRM’, Mentoring Special Issue 1, Chapter 7, 92-103.

Cerasoli, C.P., Alliger, G.M., Donsbach, J.S., Mathieu, J. E., Tannenbaum, S. I. and Orvis, K. A. (2018) ‘Antecedents and Outcomes of Informal Learning Behaviours: a Meta-Analysis’. Journal of Business Psychology 33, 203-230.

CORU (2013) Framework for Continuing Professional Development Standard and Requirements: Consultation Report. Available at: <https://coru.ie/files-publications/consultation-reports/coru- framework-for-continuing-professional-development-standard-and-requirements-public- consultation-report-2013.pdf> [accessed 10 February 2020].

Davidson, J.C. (2005) ‘Professional relationship boundaries: A social work teaching module’, Social Work Education 24(5): 511-33.

Davys, A. and Beddoe, L. (2000) ‘Supervision of students: A map and a model for the decade to come’, Social Work Education 19(5): 437-49.

Hand, H. (2006) ‘Promoting effective teaching and learning in the clinical setting (learning zone: education)’ Nursing Standard 20(39).

Hoque, M. (2017) ‘Three domains of learning: cognitive, affective and psychomotor’, Journal of EFL Education and Research 2: 45-51.

Inzer, L. and Crawford, C. (2005) ‘A review of formal and informal mentoring’, Journal of Leadership Education 4: 31-50.

IASCE (Irish Association of Social Care Educators) (2009) Practice Placement Manual. Available at: <http://staffweb.itsligo.ie/staff/pshare/iasce/Placement%20Manual%2029mar09.pdf> [accessed 12 February 2020].

Kadushin, A. (1992) Supervision in Social Work (3rd edn). New York: Columbia University Press. Lalor, K. and Share, P. (2013) ‘Understanding Social Care’ in K. Lalor and P. Share (eds),

Applied Social Care: An Introduction for Students in Ireland (3rd edn). Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

McAllister, L. and Lincoln, M. (2005) Clinical Education in Speech and Language Pathology, Methods in Speech and Language Pathology Series. London, Whurr Publishers.

McSweeney, F. (2016) ‘Supervision of Students in Social Care Education: Practice Teachers’ Views of Their Role’. Available at: <https://arrow.tudublin.ie/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?article=1032&context=aaschlanart> [accessed 12 February 2020].

McSweeney, F. (2017) ‘Themes in the supervision of social care students in Ireland: Building resilience’, European Journal of Social Work, 21:3, 374-88.

McSweeney, F. and Williams, D. (2018) ‘Social care students’ learning in the practice placement in Ireland’, Social Work Education 37(5): 581-96.

Megginson, D. and Clutterbuck, D. (1995) Mentoring in Action: A Practical Guide for Managers. London: Kogan Page.

Morgan, M. and Rochford, S. (2017) Coaching and Mentoring for Frontline Practitioners. Dublin: Centre for Effective Services.

Morrison, T. (2003) Staff Supervision in Social Care. Southampton: Ashford Press.

O’Neill, G. and McMahon, T. (2005) ‘Student-centred learning: What does it mean for students and lecturers? Emerging Issues in the practice of university Learning and Teaching’. Available at

<https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241465214_Student-centred_learning_What_does_it_ mean_for_students_and_lecturers/citation/download> [accessed 10 February 2020].

Randall, V. R. (2011) ‘Learning domains or Blooms Taxonomy’. Available at: https://academic.udayton. edu/health/syllabi/health/unit01/lesson01b.htm> [accessed 12 February 2020].

Reece, I. and Walker, S. (2007) A Practical Guide to Teaching, Training and Learning (6th edn). Tyne and Wear: Business Education Publishers.

Rogers, A. (2014) ‘The Classroom and the Everyday: The Importance of Informal Learning for Formal Learning 1’. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311419581_The_Classroom_and_ the_Everyday_The_Importance_of_Informal_Learning_for_Formal_Learning_1> [accessed 12 February 2020].

Rogers, R. (1957) ‘The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change’, Journal of Consulting Psychology 21: 95-103.

Saliba, M.T. (2014) ‘Educational assessment tools for an equitable supervision’, Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences 116: 321-7.

SCI (Social Care Ireland) (2015) Continuing Professional Development Policy and Portfolio for Social Care Workers. Available at: <https://www.socialcareireland.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/CPD-Portfolio. pdf> [accessed 24 January 2020].

Taherian, K. and Shekarchian, M. (2008) ‘Mentoring for doctors: Do its benefits outweigh its disadvantages?’, Med Teach 30(4): e95-9.

Taylor, D.C.M. and Hamdy, H. (2013) ‘Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education’, AMEE Guide No. 83, Medical Teacher 35(11).

Turpin, M., Lynch, D., Spermon, D. and Steel, E. (2015) ‘Preparing Students for Health and Social Care Practice through Inter-professional Learning’, 38th Annual Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia Conference (HERDSA 2015): Learning for Life and Work in a Complex World, 6-9 July 2015, Melbourne, Australia.

UNESCO (2009) Global Report on Adult Learning and Education. Hamburg: UILL.

- The following resources provide in-depth explanation of the three learning domains: Randall, V. R. (2011) Learning Domains or Blooms Taxonomy. Available from: https://academic.udayton.edu/health/syllabi/health/unit01/lesson01b.htm Hoque, Md. (2017) ‘Three Domains of Learning: Cognitive, Affective and Psychomotor’, The Journal of EFL Education and Research, 2. 45-51. ↵

- Reproduced with permission from student reflective assignment ↵